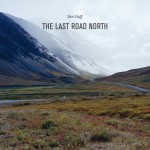

Dennis Witmer: The States Project: Alaska

Dennis Witmer was born in Lancaster County, Pennsylvania in 1957, began making photographs in 1977 as an undergraduate at Millersville College in Pennsylvania. In 1985, he was accepted into the graduate fine art photography department at the Rhode Island School of Design, but after completing an interview there, elected to decline the offer, and instead spend time photographing in the American landscape. His move to Alaska in 1987 in order to spend more time making photographs was a direct result of this decision.

Over the past decade, Witmer’s work has been included in over 75 exhibits, including twenty five one person shows, including the Anchorage Museum of History and Art, at the Blue Sky Gallery in Portland, Oregon, and Visual Studies Workshop, in Rochester New York, and numerous invited and juried shows, including Gallery Sink in Denver and at the Stephen Daiter Gallery in Chicago. His work is included in the collection of the University of Alaska Museum, the Alaska State Museum in Juneau, the Anchorage Museum of History and Art, and in many private collections.

You moved from the East Coast to Kotzebue almost thirty years ago. That drastic change is hard for me to conceive. What were your first impressions of the place?

Two impressions—first, getting off the jet–the town of Kotzebue was (and is) a dump— though I’ve developed an affection for it—it’s an honest place, very little pretension of being anything other than a group of people hanging on to the edge of the world. The sadness of the place is when people fall off, which they sometimes do. The other first impression–my wife and I spent our summers on the tundra about 100 miles east of Kotzebue—I remember my first trip up the river—I told my wife “there ain’t nothing here”—a statement made in awe of the space. In the beginning, the space scared me—if we got into trouble, it might be weeks before anyone came looking for us—but eventually the space became intoxicating, addictive.

Did you take up to making pictures immediately?

I began making photographs fairly seriously about a decade before coming to Alaska— and my intention in coming to Alaska was to make pictures—so, yes, I began making pictures of what I saw immediately. I didn’t understand what I was seeing, but making pictures is a way of making sense of what’s in front of me.

You are an avid book collector, and I know you have great knowledge, and appreciation, of many photographers of the American West – does this influence your work in the North and Interior?

I agree with Szarkowski when he states that an artist cannot afford to be ignorant of the tradition he is working in. When I moved to Alaska in 1987, the internet did not exist, so I tried to study the work of others through books and purchased as many as I could. Immediately, before moving to Alaska, I spent a year in northern New Jersey, and my wife and I would go into Manhattan and go to the Strand Bookstore. I bought several dozen books then—this would be in about 1986—that I took with me to Alaska—Lewis Baltz, John Gossage, Lee Friedlander, Atget, Edward Weston, O’Sullivan—and especially Robert Adams—that formed the core of my library. It was just after the death of Ansel Adams, and it seemed like the whole world was trying to be the next Ansel Adams, but I didn’t trust his work. I think I mostly seized on Robert Adams view of the world, with the man-altered landscape “New Topographics” vision as something I wanted to work with. But being aware of what has been done already is only half the benefit of knowing a tradition—the other part is realizing what hasn’t been done. And Alaska hasn’t really been done—just a handful of images from Ansel Adams and Brett Weston from the mid-century, and a few one-offs from more current photographers (I love the Alaska images in Friedlander’s ‘American by Car’), which is not to dismiss this work—but nobody has ever created a sustained body of work in Alaska comparable to Weston or Ansel Adams or Robert Adams. While some claim that a place doesn’t exist until it has a poet, I think the same can be said of photography—a place doesn’t exist until someone has created the defining photographs of it. And in that sense, the Alaskan Landscape hasn’t been defined yet. Of course, it takes a bit of arrogance to define that as your goal, and I didn’t start out trying to do that. But I did set out with the goal of trying to find out what remained of the frontier, the Alaska wilderness—although I don’t claim to know what either of those terms mean.

During my first summer, making my first pictures of the open land, I would deliberately include any human object I could in the frame, trying to be honest. It took a while (and a very helpful conversation with Richard Misrach) to recognize that it was OK to make pictures of empty space—if they were honest pictures. I think it’s dishonest to make pictures from the edge of the road without also making some pictures that also include the road, so the viewer knows where you stand. (Which is what I dislike about Ansel Adams—he basically invented the wilderness from roadside pull-outs—in the long run, it feels like one has been conned.) But in Alaska, the space is still there, so pictures of it can still be true, and enjoyed for what they show. And those pictures hadn’t been made. Alaska has a different sense of light and space than Yosemite, but it takes a long time to learn to read the space, and figure out how to get it into a photograph. What I think I did learn from Robert Adams was his use of space—I think the space is the real subject of his work—skies and distant horizons—and I started going after the space. My wife told me to keep getting bigger cameras—I started the first summer with a 4×5—switched up to 8×10, and spent some time with a 12×20—but even with a big camera, the space is elusive.

We’ve talked about this before, but does Alaska have a place at the table in discussions about photography of the West or is it something all its own?

Well, I think it depends on who’s table you’re sitting at. If it’s my kitchen table, then the answer is yes. But obviously Alaska is not considered as part of the discussion in other circles—one example we’ve discussed before is the book “Into the Sunset: Photography’s Image of the American West” published in 2009—it contains images by Cindy Sherman and Diane Arbus—but not a single picture from Alaska. Perhaps that isn’t a bad thing—maybe Alaska retains a mythology all its own—but it feels more like just being ignored. Or maybe it’s because nobody has ever really gotten the place— made the defining pictures—so it isn’t included in the discussion.

What has kept you going for thirty years? What is it about the landscape that sustains you?

Well, it sure as hell isn’t fortune and fame that’s kept me going. But the older I get, the more I understand Robert Adams remark: “We’re in it for the view”. I like the feeling of putting the 8×10 in the back of the van and heading out for a day, looking.

Do you feel as though there is a photographic community in Alaska?

I think that Robert Adams is right when he argues that it isn’t enough to make photographs for yourself and that there has to be an audience somewhere for the work. Living in Fairbanks means that you aren’t in the center of the Art World—it isn’t New York or LA—and there weren’t that many people in Alaska who understood what I was trying to do. That seems to be the cost of living in an interesting place and working it from knowing it, rather than flying in, taking a few shots, and leaving. It’s hard to find people who can help. I did find people outside Alaska that did understand and were encouraging. To drop some names, I’ve had wonderful conversations with Richard Misrach, Emmet Gowin, and Robert Adams over the years. Some of the conversations were only a few minutes; some were for hours—but knowing that photographers like that understood what I was trying to do helped immensely. In the end, I tried to create a small community of photographers in Fairbanks—we did “book nights” at my house—wonderful discussions—I don’t know why it took me so long to start them. But it was a wonderful way of showing people work that I like and respect, especially to a younger generation. The web has changed a lot—as has digital photography—it’s now easy to look at a lot of images from almost anywhere in the world—and the digital revolution means that there are a lot more “perfect pictures” out there—but I still think it is hard to find important work. By that I mean work that helps me find the next pictures I need to make.

What are the obstacles to making work in Alaska?

Frostbite, hypothermia, winds, mosquitoes—but mostly the space. It takes time to get out there to look, and a long time to understand what you are seeing. And isolation. The months and years between good conversations. But, of course, that is tempered by having the most amazing landscape to work in, and the giddy feeling of having it all to yourself.

After twenty-six winters – between Kotzebue and Fairbanks – you’ve recently moved your family to Spokane. Although you come back to Fairbanks often, do you feel a pull to move back?

I moved to Alaska just before turning 30—I’m now 58—and have no regrets about the time spent in Alaska, or the decision to leave. Much of Alaska remains wild, almost beyond imagination. It still seems possible to walk into that space and disappear, and the place would remain unchanged for your passing. But I feel like I’ve done my work there—I’ve gone as far as I have the energy to go. We moved south to be near a small farm we purchased while living in Kotzebue. Over the past weekend, my wife and I worked on planting a garden, taking breaks on the front porch with a view of distant mountains. I enjoy putting things into the dirt and hoping for them to grow. It is a landscape on a human scale, a place we can take care of, and hope will take care of us. I was in Alaska on business just a week ago—it involved traveling out to several villages near Fairbanks—I sat in the front seat and took pictures with a digital camera through the cracked and mud spattered windshield—and we passed many places where I set up my tripod and photographed over the decades. But I feel no urge to move back. I miss Fairbanks, but not that much. I miss the space of the country, but I have many photographs already. I think I’ve done my work there.

I know you have a massive archive of work. You’ve self-published two books – Front Street, Kotzebue and Far to the North. What’s next?

I have two other book projects in “semi-finished” form—meaning that the editing and sequencing are mostly done. The first is a group of landscape photographs selected and sequenced by Robert Adams; the second is a collection of images from interior Alaska matched with poems by John Haines. I’d been hoping to find someone to help with the publication of these projects, but so far that hasn’t happened. Beyond that, I do have boxes of prints quietly aging on shelves. A few days ago, I opened one box of images taken in Fairbanks in winter—some of the images are now more than 20 years old. They seem to be aging gracefully.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Naohiro Maeda: Where the Wild Things AreDecember 26th, 2023

-

Adam Ottavi: The States Project: AlaskaMay 2nd, 2015

-

Ryota Kajita: The States Project: AlaskaMay 1st, 2015

-

Chris Miller: The States Project: AlaskaApril 30th, 2015

-

Brian Adams: The States Project: AlaskaApril 29th, 2015