Photographers on Photographers: Ally Caple in conversation with Daniel John Bracken

Daniel John Bracken and I met in undergrad. Within the past five or so years we’ve been honorary roommates, then real roommates; he’s been my TA, my barista, my muse, my free ticket into the Met once pay-what-you-wish admission changed — real friend shit.

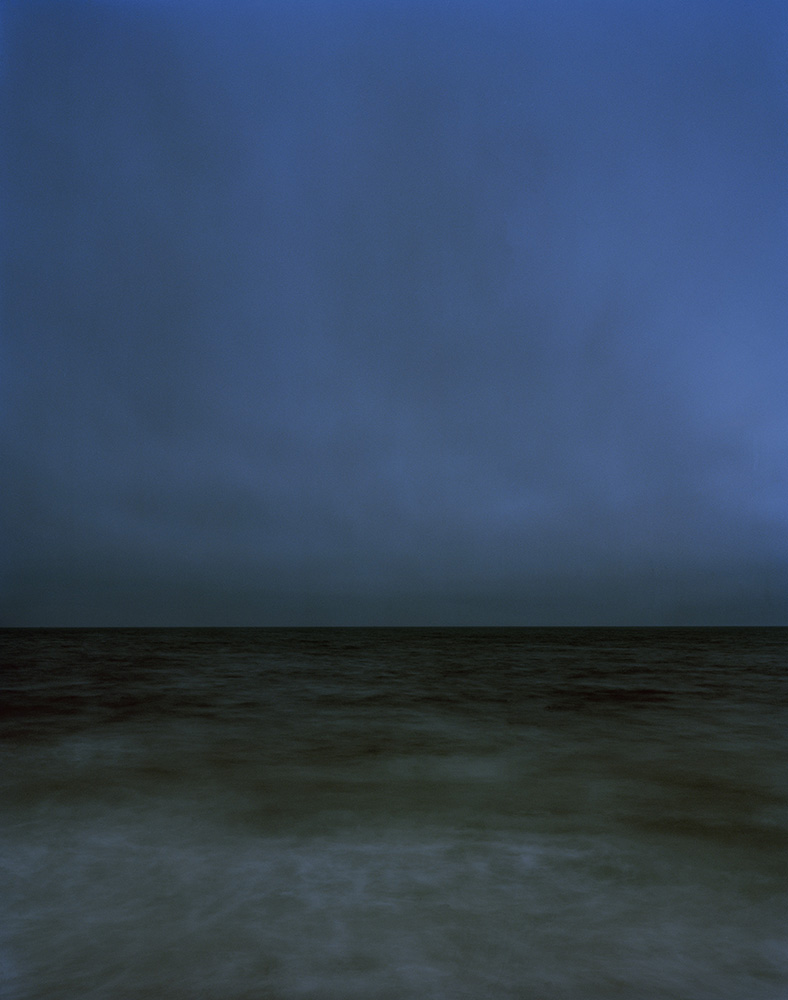

The last time we spent a lengthy amount of time together was the first half of 2018, when he began his body of work now titled I’m You, Just Here. We lived together out in Rockaway (New York) and I often found him heading to the beach as I was coming home from work later in the evening or heard him sneak out before the sunrise. The thing he was after — those pictures — are included in this feature.

When I look through Danny’s images, the ever-shifting narrative he builds often forces me to confront my own memories, both ones I hold on to and ones I wish I’ve forgotten. There’s no in-between really. The work doesn’t leave room for mundane thoughts or pondering; even in moments of pause or ephemerality, I can assure you it’s all vital.

Ps, big congrats to Danny on just completing his MFA! I’m immensely proud of him and the work he’s created, and I’m excited to publish a bit of what we’ve discussed.

Ally Caple (b. 1995, New Haven county, Connecticut) is a photographer working and living in New York. Much of her work and thoughts have revolved around multiple forms of care as labor, Blackness, and her inherent proximity to whiteness. A graduate of SUNY Purchase College, she received a BFA in Photography and BA in Arts Management in May 2017. In 2019, she completed the Education Practicum at the Studio Museum in Harlem and attended the Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture. She is an active member of the Skowhegan Alliance.

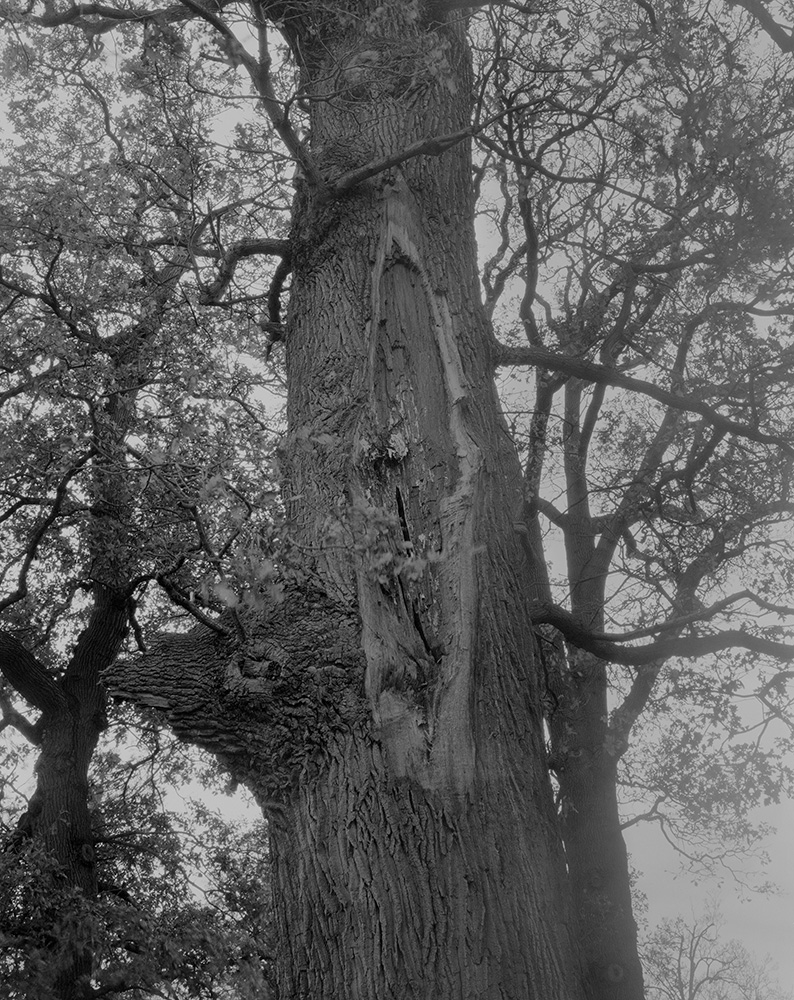

Daniel John Bracken is a London based visual artist working primarily with photography. Originally from New York, he has just recently finished his studies at the Royal College of Art. His research draws from alien abduction stories and modernist literary narratives, coalescing his practice around investigations into memory regression and the ontology of the photograph. With a focus on Virginia Woolf and Victor Turner, the artist draws connections between the experienced and the imaginary – realizing an unconscious gap between what we remember and what we wish to forget.

He has had works included in a number of group exhibitions and publications that have been displayed throughout Europe and the United States. Recent features include C41 Magazine and Der Greif, with forthcoming exhibitions in London, Manchester, and Athens. Daniel has also been accepted into the Residency Program at The Burren College of Art, Ireland for November of 2020, where he will be furthering his photographic investigations into natural and abstracted phenomena.

Ally Caple: Some of the buzzwords / topics that overlap in your research between your two recent bodies of work are memory, time, inheritance, queer identity… Can you speak more specifically on how these concepts inform your work?

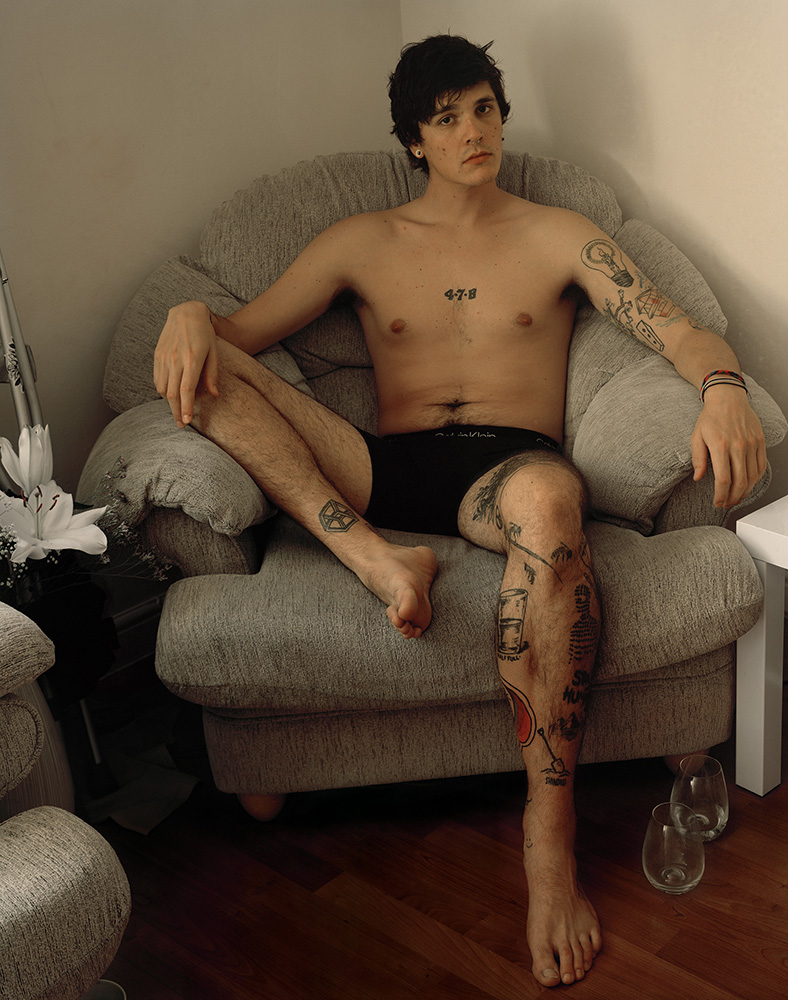

Daniel John Bracken: I see the works always drift between being informal narratives and studies that act against time. When I think of memory, I instantly think of the photograph, and the pause. I think about what it is that we choose to hold on to. The images act as metaphors for my personal experiences that are forced to be frozen and reconsidered. Queer identity becomes something that is always within the images, and so it’s inherited by them. Almost like narrative tools, this inherited identity directs and questions the works simultaneously.

It all becomes a bit like a mashup between a Rick & Morty episode and a Cookie Mueller story. The work is made in the present but it references the past, the future, the assumed and the unexpected.

AC: You’ve mentioned off-record that your work lives in a non-linear plane of existence. When it comes to sequencing your images, how do you present the pictures in order to achieve this kind of read?

DJB: I’ve noticed that my photographs do tend to mirror each other quite a bit – either literally or metaphorically. Kristine [Potter] once compared my earlier works to “secrets” that the viewer has to decipher. I like to think of the images that way still, almost like unresolved lines in a poem. When displaying the photos physically, I always try to keep the portraits at eye level, with other images seemingly floating or falling away. They act to anchor the space, catching the gaze of the viewer and mirroring back onto themselves. I also show them in a way that lets them reflect each other; for example, in a recent exhibition I matched the gaze from Untitled (Self Portrait), 2019 with that from Brody, 2019. Originally meant to be parallel to one another, I realised that a perpendicular hanging (a bit more “Salon Style”) not only informed the images, but sparked a certain dialectic among the works and forced a way of viewing. Likewise, I tend to reflect time as it shifts around still life: sunrise into sunset. I try to manipulate space and slow time with the 4×5 to directly challenge perception between the lens and the eye. My affinity for Virginia Woolf and Ursula Le Guin really inspire that narrative strategy on perception; on looking. I’ve tried to make some of the photographs quite fragile and others quite heavy. Some stay grounded in time while others seem to fall out of it. Though space may act to change the way the photographs exist within a space, I tend to fall back on my knowledge of sequencing within a book to maintain the gesture of poetry with the hanging of work. The photographs can be stood in front of, breezed past, or gone back to — much like flipping the pages of a book.

AC: Do you typically know the intent of a photograph you want to make prior to or in the moment of making it, or do you tend to figure it out later on?

DJB: Intent in photography changes for me quite often, usually on the grounds of what cameras I’m using. I tend to switch between large and small format cameras often, and I always find that either format informs the other when making a completed image. Initially, I do prefer working with a 35mm as it’s easy, it’s fast, but there’s still the importance of the images being on film and being trapped before being presented. This makes me think less, act more, but still reflect on the image. These usually end up being the photographs I make of friends, at clubs, of my experiences: usually blurry, sometimes beautiful, sometimes solemn, but always charged. These photographs are works themselves, but also become the framework for the large format photographs that tend to come at more meditative paces. I take a really long time to make the “perfect” picture, so the large format images are really intensely coordinated, but are always informed by the faster-paced moments that brought them into thought. I guess in that way, I always have at least two projects going on or coinciding at the same time — one which is this cataloging of my own life, a more personal autobiography, and one that acts as a more refined retelling of those experiences. I think both have the intent of telling a narrative, but they require a different amount of time to unravel their meanings; one is a reflection of the moment, while the other is something that figures itself out a bit later on.

AC: You’ve mentioned the idea of the perfect image… What constitutes this for you in your current practice? Similarly, how did you know when these two bodies of work felt complete? I’ve always been intrigued by your bodies of images only containing a handful of pictures (in this case both I’m You, Just Here and It’s Safe Behind the Glass each have nine.) Is it your intention to keep the quantity of images short, or did the work allude to that on its own over time?

DJB: When I’m referencing the perfect image, I’m considering a few things: One of them being the hope that whatever I’m experiencing could become a reality. Along with that, I’m usually focusing on the perfect neg: lighting, processing, scanning, retouching, printing. I’m also usually pretty concerned with how the image alludes to the other work — how it connects with both previous and future photographs. In that sense, when I’m talking about the perfect image, I’m realising the outcome of all those preconceptions and whether the outcome does its job. Tells the right story. Then it makes it to the wall and I have to see if someone else thinks it’s a perfect image. So, that kind of breaks the idea up a bit. I don’t think images can be perfect, but I do think there’s a certain sense to an actualised, practiced, or mature photograph.

With reference to the bodies of work, I think the idea of maturity in practice comes into play even more so. Generally, I tend to under-edit for quite a while before making fully realised decisions about a final selection, meditating with works that sometimes never end up being seen by anyone else. I think, by integrating that into the practice, I’ve taught myself to realise what’s more and what’s less actualised — which images could use some more work and which could stand on their own. To be honest, most of the time my initial reactions are quite different from those of other people, but even that helps in the long run. As for the projects themselves being quite short: I’d say that still comes from a really concerned edit, but also my attempt at both bridging and breaking gaps between old and new works. Photographs from nearly three years ago have now recently become really important to the work that I’ve been making since January, and yet most of what I’ve produced in 2019 stands as separate sequences. There’s something of an internal dialogue that happens within the works for me — while they generally can coexist (and usually do, in cases of publications) I try to differentiate them as they touch on different aspects of the overarching themes I’m trying to explore. They’re almost like different chapters to a whole story. That was a really good question to sit with… I think I might try to show the “whole story” sometime soon.

AC: How have your photographs allowed you to perceive the world? And do you think you remember through photographs or do photographs help articulate how you’ve remembered?

DJB: Honestly, I think the power of the photograph is that it can be both: they are a memory made physical, but also a story that we remember. Photographs are the string that connects history with myth. My photographs force me to stop more often; they make me lose my own sense of time because I become lost in light or emotion. I want to see everything (and feel everything) in a moment and somehow put that into the image — to express that curiosity of being. But I think that can be said of most photographs, or most memories… Some of us are just more keen on shaping our memories alongside others’ memories in a gelatin copy. It’s poetic, it’s soft, and sharp and confusing, but it’s a way of creating our own narratives that live beyond us. It reshapes our own perception on being, while also making an impact on the collective subconscious. Even if the photographs we make are never seen again, we still have that tiny sliver of a memory that for whatever reason we chose to make something we’d seen, frozen forever.

I don’t think we can limit our perceptions and memories to being influenced just by what we remember, or what we have seen, instead we have to be open to the experiences of others and the memories that others present as photographs. The Ballad [of Sexual Dependency] does it beautifully, collating lived experiences that become a diary made public. Felix Gonzalez Torres did it quite impactfully as well with his billboard work and Carrie Mae Weems has forever influenced, for instance, the way we experience the kitchen table. These moments made frozen (that for many had already been relevant and charged) become recharged or even heightened for others through these photographs. They become a visual memory bank that is constantly expanding and reshaping the way we look and the way we remember. Back to photographs being the string between history and mythology — they’re one of the strongest ways that we reclaim, reimagine, or just simply remember what was.

© Daniel John Bracken, Père Lachaise Cemetery (Unearthed Grave), 2020, from It’s Safe Behind the Glass

AC: While your work is deeply rooted in the context of history, memory, and death, it also makes me think about the longing for the ideal lifestyle or idea of a utopia. How do you interpret the relationship between the concept of Utopia and photography?

DJB: What I can think of when talking about Utopia draws from what I previously said about the impact of the photograph. I think when we start to realise the power of the photograph — socially, culturally, historically, and mythologically — we can begin to change the systems of a society as they are. Obviously documentary photography lends itself to this, but I am talking more strictly about art photography. Photographs pose a question, even if it’s one of absurdity. They make us question all that we know and see within a moment.

With reference to my own work, Père Lachaise Cemetery (Unearthed Grave), 2020 is something I regarded as absurd upon initial realisation. Even making the photograph was the hardest thing to do, I was cramped between headstones in the rain in Paris with my view camera, trying desperately to make this image. It was all a moment of intense interest and evocation, without the planning I’m used to — I just knew that I wanted that absurd, grounded, shocking image. Two months later, I had made a few more photographs in the series, Behind the Glass, 2020, the Still Life, 2020 diptych, and Untitled (Fall), 2020. Those works would be the last photographs I made before going into isolation. In the true essence of “absurdity,” I realised that I had made an entire spanning project about isolation, this “collapse” of time, and a retreat into spaces of obscurity before ever even living it.

I think that’s what’s so important about this collective sort of photographic memory and about visual language; they pose a question to us without a clear answer, and without being aware of how or when we create that answer. When I think of Utopia, I think of a reclamation of what has been lost or forgotten — the natural world, a shift in our time and experience. My photographs don’t necessarily have an answer for how we can reclaim space, be in a body, or oppose oppression. They instead depict moments of opposition within our accepted perceptions, pushing against the phantom hands of gravity and time. I think it’s those moments of confrontation that lead to what could be a retelling of personal or cultural history, of mythology; an act that pushes towards what could be this idea of Utopia.

Keep up with Ally here:

allycaple.net / @allycaple

Keep up with Daniel here:

danieljohnbracken.com / @popedanieljohn

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Olga Fried: Intangible EncountersFebruary 18th, 2026

-

Anne McDonald: Self-PortraitsFebruary 17th, 2026

-

Richard Koenig: Field Notes: View from a Hotel WindowFebruary 13th, 2026

-

Beyond the Photograph: Editioning Photographic WorkJanuary 24th, 2026

-

Ben Alper: Rome: an accumulation of layers and juxtapositionsJanuary 23rd, 2026