Matthew Genitempo: Jasper

Matthew Genitempo is a photographer based out of Marfa, Texas. He recently graduated from University of Hartford’s Limited-Residency MFA in Photography. Matthew made a monograph of his thesis work, Jasper, and was recently selected by Mark Steinmetz for Fotofilmic’s Solo Exhibition Award III. He was also chosen for Lensculture’s 2017 Emerging Talent Award.

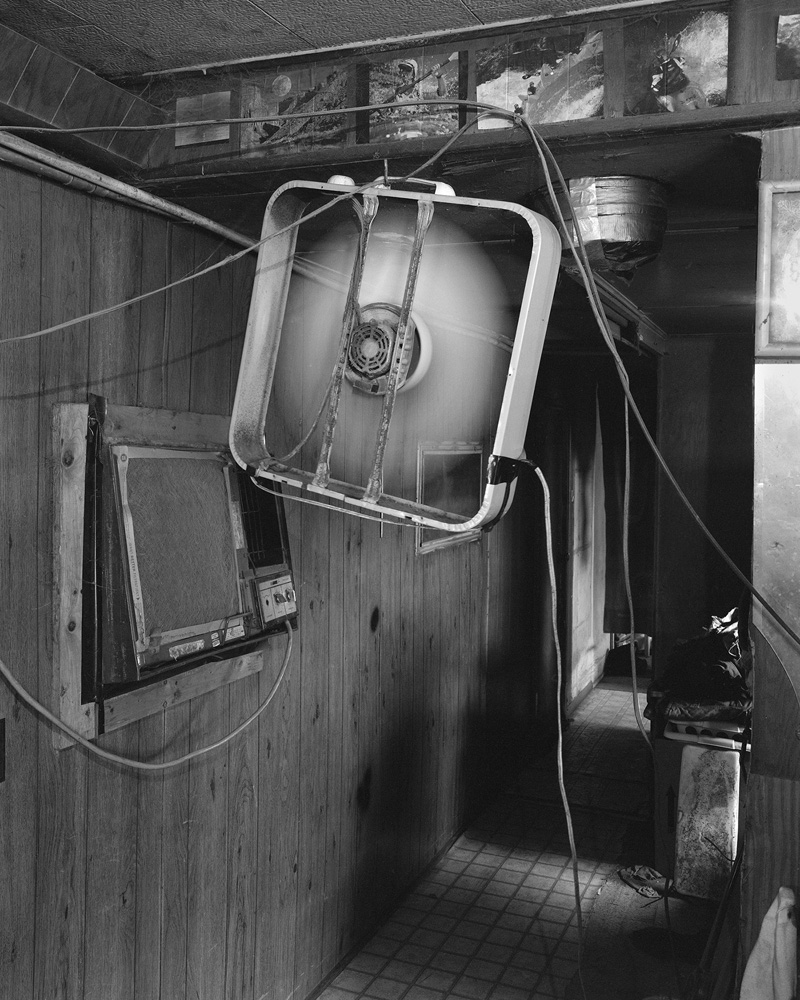

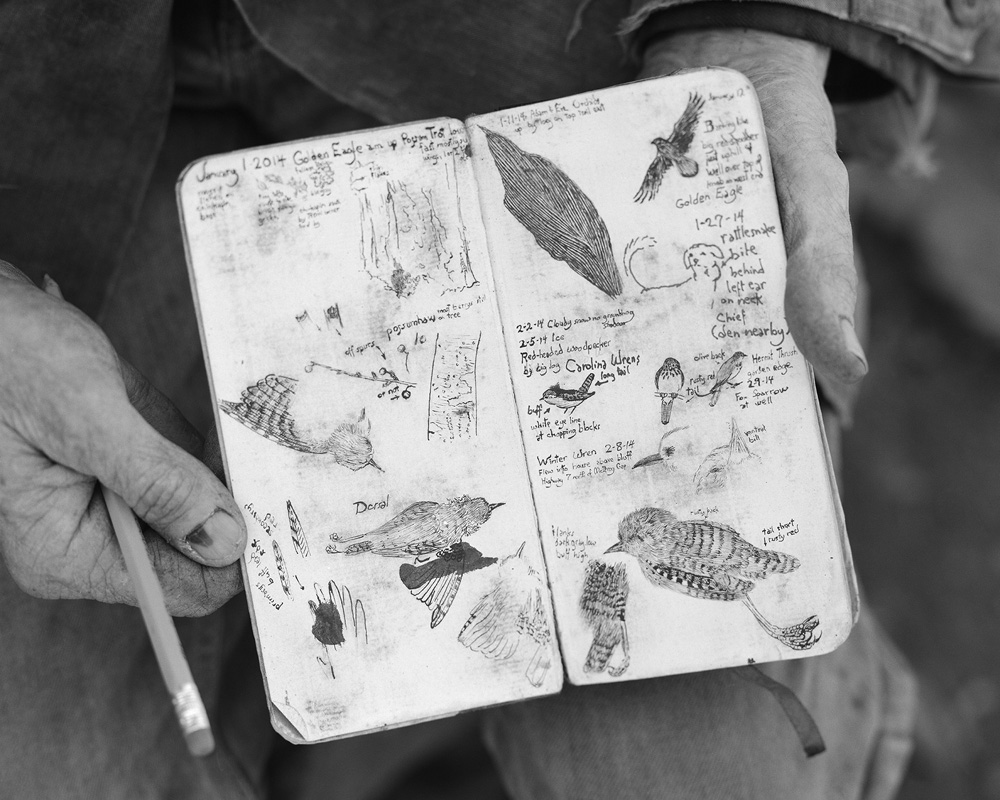

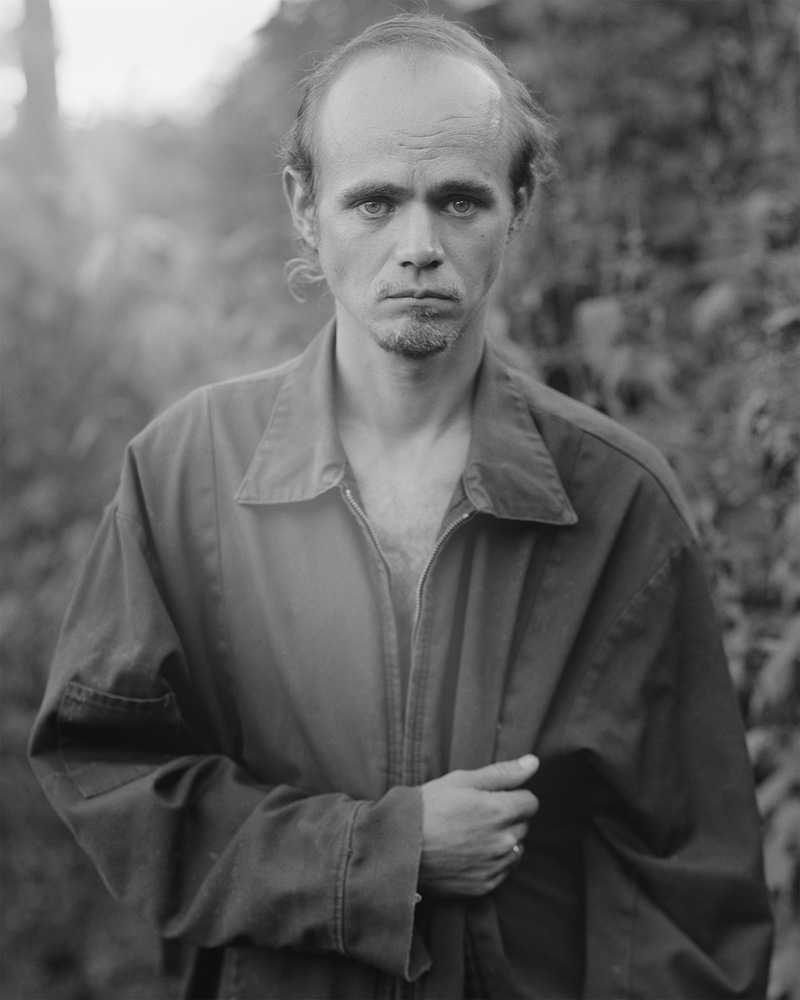

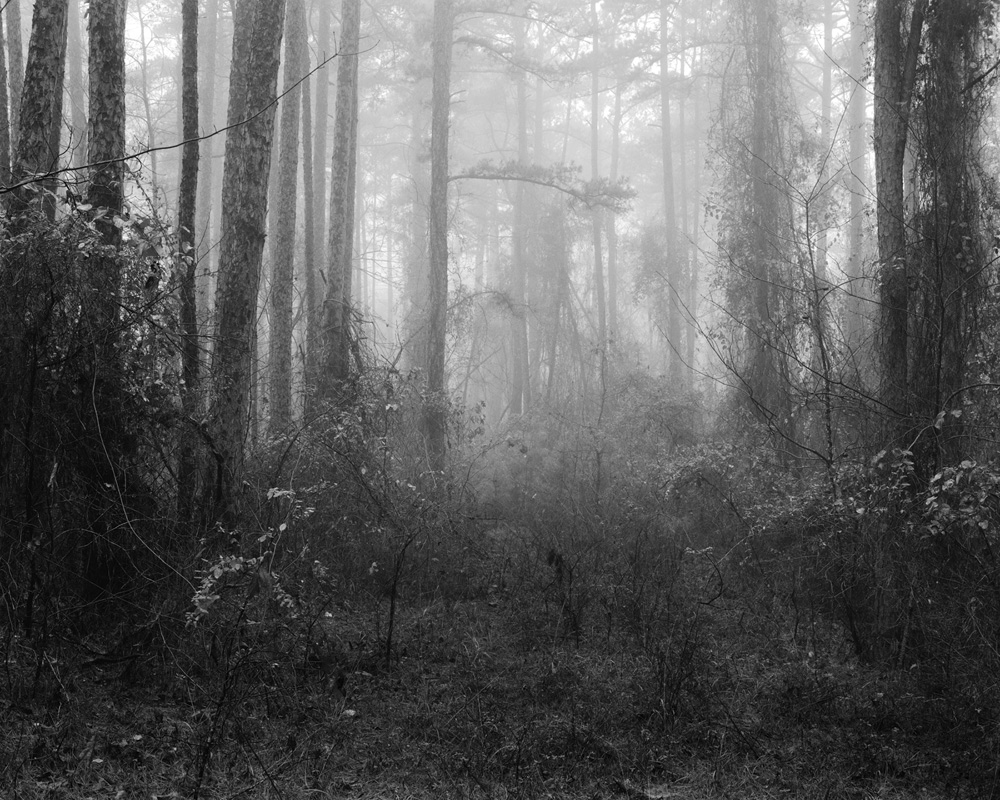

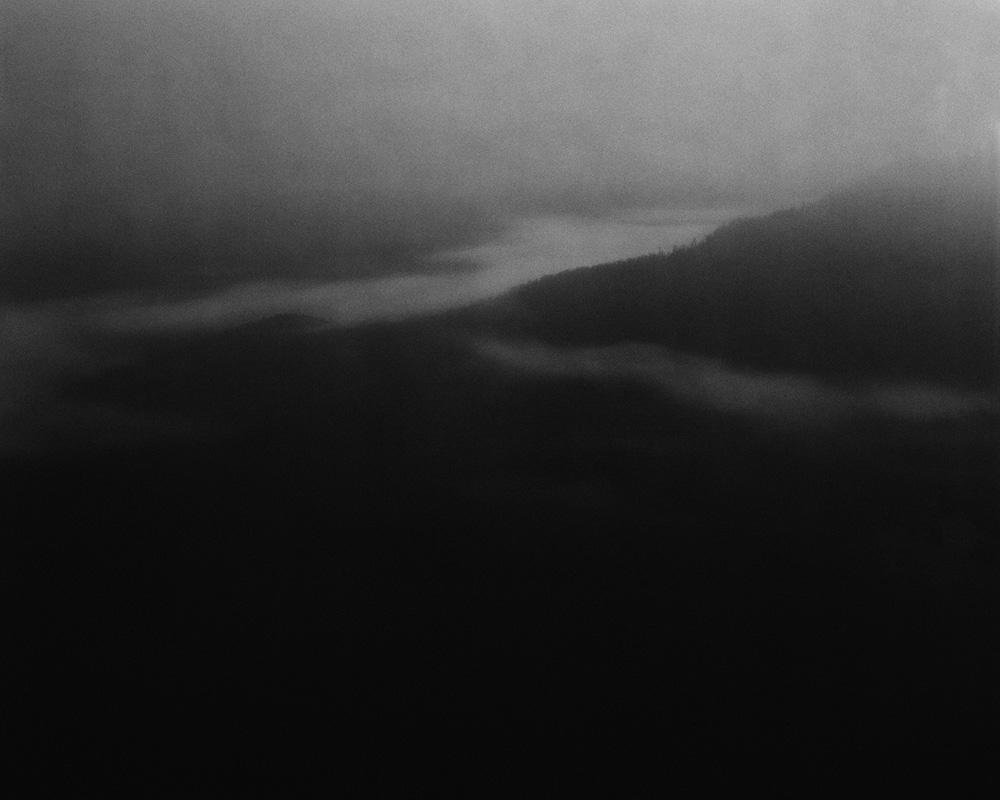

Matthew transports us into the otherworldly environment of Jasper, a semi-fictional place located deep in the woods of the Ozarks. Jasper is a universe with a rhythm of its own, almost entirely devoid of women, with hermetic male subjects living in a world of their own creation. It is unclear if Jasper speaks to escape or purgatory. Images fluctuate between detailed renderings of men in their environs to misty landscapes with amorphous forms traveling through the frames. An interview with Matthew follows.

VW: What is Jasper?

MG: Jasper is a photo project that investigates my fascination about running away from the everyday. I’m not sure I fully understand the intrigue, but I chose to examine this interest by photographing men that have lives isolated in the dark forests of the Ozark mountains. The photographs in Jasper are the result.

VW: I know that poetry has been influential to your process. What were you reading while making Jasper, and how did it help shape the work?

MG: I had a semi-obsessive spell with the poetry of Frank Stanford. I was taken by his work long before I began making pictures in the Ozarks, but when I went out to Arkansas for the first time, I brought along a copy of Stanford’s collected poems and something just clicked. After that I dove into his personal history. I drove out to spots he mentioned in his poems and visited his gravesite in Subiaco. It’s hard to describe, but sometimes it felt like his poems were inescapable and I had some sort of Stanford lens on everything. If you’re familiar with Arkansas and you’re familiar with his work, it’s tough to pull those two apart. Stanford and the land are inseparable.

It’s impossible to quantify how much he actually influenced Jasper, but I do remember rereading poems after I had come back from trips out to Arkansas and had found that I had closely illustrated lines from his work.

VW: Whose photographs are you looking at these days?

MG: I just saw David Campany’s Open Road show at the Blanton in Austin over the holidays and that blew me away. I also just received a couple of books that have been hovering around my thoughts for the last couple of weeks. One is Thomas Nolf’s “Peculiar Artifacts in Bosnia & Herzegovina” and the other is Barry Stone’s “Daily, in a Nimble Sea.” The two are quite distinct from each other but both are excellent.

VW: Some images in Jasper feel as if they could have been made during the great depression, while others place us in a more modern cultural context with a stack of VHS tapes and an 80s tv set. Your choice to render these images in black and white only furthers this sense of ambiguity with time. Can you talk about this?

MG: That’s sort of the magic thing that black and white film does. I’m not sure Jasper would have worked in color. Throughout the book you’re never really sure what is real and what’s not, so it definitely helps emphasize that phenomena when time is rendered in uncertainty.

VW: Jasper has a consistent theme of men escaping into the woods. How do you relate to these men?

MG: That’s tough to answer because I have long-standing relationships with most of these people and it’s difficult to relate to them as a group now. As a whole, I can tell you that I envy certain aspects of their lives. For instance, their independence from society, I understand the desire for that freedom, or at least I think I do, but I don’t understand the cost of it.

VW: It is hard to believe that you made Jasper in a single year while in graduate school. Can you talk about this process of shooting in total isolation in the Ozarks, then traveling to have this work critiqued in a graduate school environment?

MG: It was definitely difficult, to say the least. Returning to civilization was odd enough and presenting the work in school was another hurdle. You’re out of your element, uncomfortable for days, putting yourself on the line and you come back with a handful of pictures that are hardly a description of what actually occurred. Then you have to coherently defend them. After awhile, you step back, and the pictures tell you so much about what you’re actually doing. It’s revelatory. It was tough, but I believe that having critical conversations with people that you admire and respect was crucial to that discovery. As difficult as it was, I am not sure the result would have been as successful without it.

VW: While wrapping up this project you were simultaneously putting it into book form. How did you conceive of the book?

MG: The book might have been the most natural part of the process. I knew I wanted Jasper to be a book from the beginning. I never imagined it not being in that form

VW: This work was made during the rise of Trump, and a vast majority of his support came from disenfranchised white men in rural America. The subjects of Jasper fall into this same demographic. Do you see a relationship between the two?

MG: Personally, Trump’s iniquity permeates throughout everything during my day. It’s difficult not to find a relationship between the state of America and everything I make or take in. I can’t speak for these people, but I don’t consider them disenfranchised. From what I observed, they don’t seem too fond of politics in general. Most of these people have been out there for decades. They’ve already considered their place in all of this and have chosen to remove themselves.

VW: What’s next for you?

MG: I recently moved out to Marfa, Texas. I’ve been traveling to the West to make pictures for over a decade and that is entirely different than actually living here and making pictures. When you’re traveling to make pictures there is the pressure of time. You have to make work now because you have to return home. I thrive in situations like that. I’m finding that when you make pictures where you live, you have to summon that motivation from a different place. I haven’t figured it out yet, but for now I’m just enjoying being here and making pictures when I can.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Suzanne Theodora White in Conversation with Frazier KingSeptember 10th, 2025

-

Maarten Schilt, co-founder of Schilt Publishing & Gallery (Amsterdam) in conversation with visual artist DM WitmanSeptember 2nd, 2025

-

BEYOND THE PHOTOGRAPH: Q&A WITH PHOTO EDITOR JESSIE WENDER, THE NEW YORK TIMESAugust 22nd, 2025

-

Beyond the Photograph: Editorial Q&A with Photographer Tamara ReynoldsJuly 30th, 2025