Interview with Joel Meyerowitz: Where I Find Myself

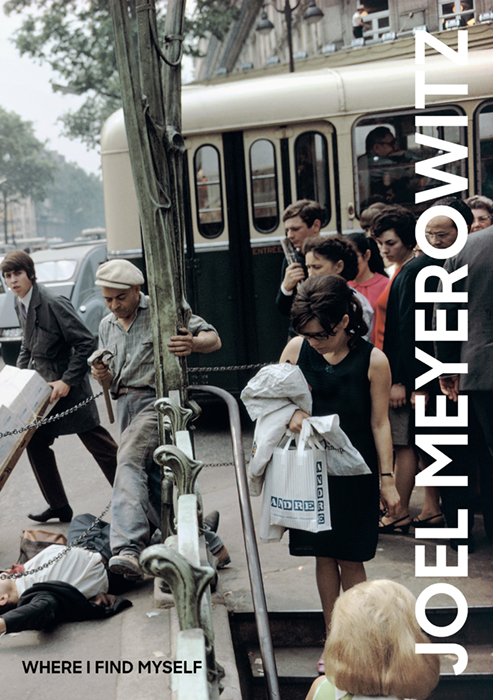

“Joel Meyerowitz: Where I Find Myself, published by Laurence King in March 2018 is the first major single book retrospective of one of the world’s most influential photographers, Joel Meyerowitz. This timely new book, published to coincide with the photographer’s 80th birthday, spans Meyerowitz’s whole career in reverse chronological order, including his harrowing coverage of Ground Zero and his iconic street photography work.” (From the book press release)

I had the privilege to have this insightful interview with Joel and hear, in his own voice, about his new retrospective book Joel Meyerowitz: Where I Find Myself, now on sale (laurenceking.com, $65).

This is a unique retrospective book in the sense that it actually starts with the present and goes back in time. This concept really does take the viewer in a unique journey of understanding the photographers style, esthetics and over all process. How did this idea and book design come around? What does it mean to you, has the artist, to present your photographic journey in this method?

Well, you know, it’s interesting how any book comes into shape. I had a larger two volume retrospective book published by Phaidon about five years ago. And they, at the time, made a limited edition book which cost about $750 and they were going to publish a trade edition at a much lower price, but they didn’t sell all the books. So I decided I’m going to go ahead and make a new retrospective version. And I thought, you know, this is a retrospective. You’re looking back from where you are over the course of your history, and of course the tendency is to always start from the past and work your way into the present. I was discussing this with Maggie Barrett, my wife who is a writer, and she said, ‘well, you know, you’re in the present and you can see all the way back through the different changes in your life. This seems like a great starting point.’ and we both had a kind of shocked look on our faces and we thought – this is fantastic. We’re going to edit the book from that perspective because the title of the book is ‘Where I Find Myself’ and I felt that there is a double entendre in that as we wander around, we always wonder how we got where we are, and photography is the medium that took me to all these different places in my life. And so, I’ve not only discovered myself as a photographer, but I’ve discovered myself as a man through 55 years of photography. In a way it’s how I had my own self discovery and I thought this title and this perspective on it is absolutely a wide open way of reviewing the work.

From the very first page, and even the cover, there is a very personal, journal like feeling to the book. We are accustomed to see, specifically in retrospective books, a more distant tone, as if there is a narrator talking about the artist. Your book feels as if you are taking us by the hand down memory lane, down your visual story. Can you tell us about this concept and why it was important for you?

Well, you’re absolutely right about the tone. Too many times artists feel that they don’t have the capacity to describe their process. They often feel that they’re defending their works rather than demystifying them. I’ve always believed – for the whole length of my career, that photography has been treated as this kind of mysterious subject. You have to have equipment, you have to have a dark room, you have to know f stops and shutter speeds and all this Mumbo jumbo that makes it seem like it’s an arcane field of inquiry.

When I thought, hey, you learn how to use the machine, then you walk around in the world and you see who you are by the way you respond to things in the world. I wanted this book to be not just a defense of my photographs or an explanation of my tactics. I wanted to say, look at this unfolding stream of events that brought me to where I am today. I couldn’t know when I began in 1962 what the road forward was going to be. It’s always a mystery. When you’ve lived for 50 years as an artist and you look back from this vantage point at all the things that lined up in the course of your evolution, you get a chance to see how linked they all were to each other, and you might be blind to it at the time, but later on they seem like the most natural arc. Even when you come to a fork in the road and you think, oh, should I go left or right? And you choose to go, right? That’s your life. You’ve made that choice and you remember the fork in the road. So I thought using this strategy to unravel my own history, will give me an opportunity to write some brief essays about the changes that happened to me because, as I look back, I see I’ve made seven or eight distinct evolutionary changes in the course of these 55 years. I thought by sharing what was going on for me at that time, I might be able to give something to the younger generations of photographers who are on their own pursuit of their works so that they too can have a sense of confidence that sure you make this decision, it’s not the end of the world, it’s just the next decision and you take it from there.

In the very beginning of the book you talk about the differences between the 35mm and the large format camera. You describe them as two languages that you are now able to talk in visually. I am sure many photographers would agree with that, and some perhaps would disagree. You call the large format classical vs. the 35mm as jazz – can you elaborate on the differences between the formats in your work? Do you think these formats could in some way intertwine? When do these definitions break out of the conventional rules of photography?

When I began, I used the 35mm camera and later graduated to a Leica, which is truly the most remarkable photographic instrument that anyone could use, mainly because of the way it’s designed, how it handles, its silence and its size. I learned to be on the streets and become invisible, and to riff on subjects or moments that I perceived in front of me. These things happen so spontaneously that there was no opportunity, or even certainty in those early years, or any concept of trying to arrange a structural stage for these works. They were only a response to what I was conscious of in the moment and then they disappeared. However, working with an 8×10 view camera on a tripod with a black cloth over your head, is a far different experience than 35mm. Besides it being slow – you’re visible. People see you with this cloth waving in the wind and the big camera and the legs and the lens, and you’re no longer invisible. So, these tactics require a different way of working, and the slowness of working with an 8×10 seems to me to be like classical music. I thought that’s an interesting way of viewing these two instruments. But there is a crossover, certainly for me, in that I think my training on the street as a street photographer gave me the appetite and the instinct and the intuition to work quickly and recognize the subject in an immediate way. Had I begun with an 8×10 camera, I don’t think I could have made the shift to the dance on the street that 35mm requires. And so I carried the view camera just like I had a 35mm, I carried it full out with the tripod legs extended and with ten holders of film in a bag on my shoulder, which was 20 shots. And when I saw something, I put the camera down, set it up fast, I put the film in, I made the picture and I moved on. I tried to treat the 8×10 camera exactly as I worked with a 35mm, given the limitations of not being able to just press a button of course, but I wanted to be in the same fast mental space so that I could react with immediacy and spontaneity and try to bring the freshness of street photography to the slowness and meditative quality of the large format.

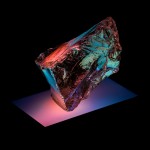

You talk in the book about how you came to start photographing these still lives in your studio. The story of the backdrop on the fence and your naive finding of these object’s photographic relevance is not only heart warming but I think for many artists- is what makes art art. Can you share with our readers, that might not know much about this side of your work, about your experience fining these objects and what is special to you in photographing them.

I’ve never been a collector of anything. I have over 50,000 prints in my archive in New York and so I collected photographs, My own. I have books, although I’m not a collector of books to the degree that say, Martin Parr is. But my life was full up with making images and so antiques and objects were of almost no interest to me, and yet a few years ago when I was working on a project with my wife on Provence, I found myself in a flea market in the south of France. I picked up these objects for this friend of mine – as I’ve written in the book – and I remember holding the objects in my hand and realizing that these things had been well used and then discarded, and by retrieving them in the way that I did, I could feel their… spirit. It’s as if something resonated within me when I saw these objects and it opened me in a way that I hadn’t recognized before. A crazy thing happened on this trip to Provence. I was in Aix, where Cézanne’s studio is, just as an artist who’s always revered Cézanne. In the studio, there were 75 or 80 objects of his that he used in his paintings and they were on shelves high up on the wall just gathering dust and I thought, I wonder what it would be like to put these objects of his on one of his tables and just look at them one at a time and make a portrait of them.

So the Director gave me free run of Cézanne’s Studio and his objects, and I took down all these beat up, discarded objects that he had used repeatedly, over many years of painting still lives, and I just studied them against the gray background that he had painted the walls and I wondered to myself, why did he paint them gray? Was there something painterly about that kind of dark neutrality? What did it do for space since? If we think about Cézanne as the father of modern art and the concept of flatness, what did that gray do for him to flatten the space? And I wanted to see if it would be visible in the photograph. Since then I’ve also looked at the objects of Giorgio Morandi because I’m living in Italy now, and he’s an Italian painter and he’s someone I’ve also had long affection for, and basically these two artists allowed me to have a dialogue with them and their objects and I’ve moved beyond that dialogue now, in the sense that I made portraits of the objects, but at this point in my time, as you could see in some of those photographs at the very beginning of the book, I’m trying to work with clusters of objects, but not in the conventional sense of Dutch still life paintings where they were about the beauty of the object or the light. I’m trying to take the energy that I recognized on the street, the way people clustered together, separated, pushed forward. I’m trying to see if in fact there is another dynamic that’s possible for still lives by using these cast off objects. Each of which I try to arrange so that part of the object that has the most vitality speaks to me, so I have a one to one relationship with each object, and then a group relationship with them, looking to see if there’s a dynamic that will make for an interesting and new kind of still life.

Through out the book you have a clear definition of a street photographer vs. perhaps a classical, landscape, “view camera” photographer. I find it very interesting to see this inner conversation you have with yourself about defining yourself or the ‘photographer’. Do you think, now after many years and moving through various genres of photography from landscape, portraits, street and now still Lives – that these definitions are important?

I think that’s a great point. I don’t think that it is necessary in understanding photography to define one from the other. I think photography is an arc that suggests you’re an artist who works with a camera and you make images about whatever interests you. So the generic term ‘photographer’ covers all. However, some people do specialize. They dig in to something, let’s say street photography, and they try to find what is it that’s so essential about photographing quotidian life on the streets of the world, what is it revealing, and what is it doing to the artist who chooses to work that way? How do they deepen their understanding of the medium and the way it describes the subject that has drawn them to it. I think, as there are post modernist artists, conceptual artists and action painters and a photo realists, people tend to carve out an area for themselves that they want to operate in and help to strengthen and define that area of interest. They take on a defining title for themselves. It can be looked at both ways, that if you’re a photographer and you say you’re an artist using a camera, then you’re a photographer, but if you need to sub divide that, then I think that’s reasonable, and I certainly did for a long time. I feel I wouldn’t call myself a still life photographer now , I’m just a photographer, but my current area of passion is – whatever the hell still life means in photography.

Looking at your book at times felt as if I was looking at a time capsule. Traveling in time and looking back at our culture, history, things that today do not exist any more, our tragedies and our good time. This is truly a journey down a story of modern culture through your eyes. I would love to hear your intake on this notion.

I think this is a very sensitive point that you’re bringing up, and I really have a lot of gratitude for your reading of the hidden text of this book and bringing it out in this form of question. Yeah. The 55 years that I’ve lived through as a photographer from 1962 to the present has had an incredible arc of history, not only of photographic history because what we see is photography coming into it’s own in the sixties and coming from the basement, you might say, where they always shoved photography, to competing with fine art, high art, up from the sort of craft of photography, up into the rarer atmosphere of fine art of today and going from black and white through color. I was one of the adventurers who started out using color in 1962 and basically arguing for the form through all this time. I feel like I’ve seen the evolution of photography into its maturing in to a really serious contemporary art form. At the same time, this trip in the arts has happened from the death of Kennedy, the Vietnam War, the moon launch, the feminist movement, the digital revolution, the invention of the computer. I mean, all of this coming to today’s ‘trumpion’ disaster, this is a whole history and in fact, if you look at some of those still lives, there’s a few of them that were done way before Donald became the president, but I was trying to make some kind of political statements about power and politics in a few of those pictures and oddly there’s a kind of trump-like character who I had no idea was going to come in to play. It can be seen when we look at any historical period that we immediately go to the photographs from that time to see the clothes that people wore, the cars they drove, the social mores and values, whether it’s a club scene or battlefield or poverty. Photography is right there alongside of our evolution, showing us what we look like. I chose to try to weave that in to the overall shape of this retrospective.

One of the things I was curious about was the book cover image. How does one choose, from years and thousands of photographs which one will represent a retrospective book? What is it about the image that was selected to be on the cover? What is it’s story?

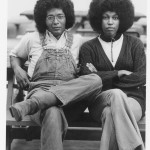

Well, this is because I did see myself as a street photographer and I wanted an image that happened on the street to represent the work. It clearly defines the ability to be conscious in a moment and reach for something that is disappearing and hold onto it with the camera, whereas a landscape or portrait or still life would, I think, shift the book’s question somewhat towards that particular genre.

I wanted to say that immediacy and recognition and spontaneity and observation are an essential part of my photographic discipline and that this picture with its inherent puzzle, would be a good one to wrap around the book so that you don’t see the whole picture at once, but maybe the incident that is visible is the thing that makes you open the book up and look at it front and back. And if you pick a book up and open it to look at it, you’re already one step closer to maybe getting engaged in the book. So I was looking for a form of engagement, and in a way the book cover is the poster for the book. In this world, with thousands of photographic books every year, you need to try to attract the reader in some way. The story about this picture, I certainly have talked about this before and in the book, but it was only one photograph. I came around the corner, I always saw a crowd. I instinctively always move towards a crowd and at the very moment that I arrived, that man with a hammer was stepping over this fallen man. I couldn’t have asked for a greater coincidence to have happened in front of me. And of course one step later he was gone. The whole thing had changed. But certainly, the question is, why weren’t all those people in Paris going to help somebody? Why those people did not, is for me, of a greater issue than the mystery of the fallen man.

Throughout the book you mention many important, iconic and memorable figures in the photographic world such as Robert Frank, John Szarkowski and of course Garry Winogrand. How did these people influence you and your photography? How did these interactions affect you? You yourself are impacting many young photographers today, and will continue to influence for generations, but we all start in the beginning and we have people who shape our minds and art.

I was born as a photographer, you might say, on the day in 1962 when my boss at a small advertising agency hired his friend Robert Frank to shoot a booklet that I had been the graphic designer of. I didn’t know anything about photography or about Robert Frank. Watching Robert Frank work was the deciding factor that make me a photographer. I gave up painting and my graduate school studies in art history, and I borrowed a camera and I went out on the street because I knew the street was where I belonged. A few months later, the art director left and he gave me his copy of Robert Frank’s ‘The Americans’, the French edition. And so twice within a number of months, Robert Frank influenced me, although he personally didn’t, his work did. I saw that there was a poetic potential in photography that I had no concept of prior to seeing ‘The Americans’.

Later that year, my wife at the time, Vivian, bought me as a present ‘The Decisive Moment’ by Cartier-Bresson. Bang. There was a second powerful, overwhelming vision of what the world could look like with a camera. It wasn’t today’s world where there are thousands of books. There were very few photographic books then. There might have been photo annuals and photo magazines, but there were no real serious photo books. I think the only other one that I came across was Walker Evans ‘American photographs’. So there were three books basically as my library and these very different books brought a world of possibility to me. My idea, right at the beginning, was that maybe someday I’d be fortunate enough to make a book if I could just learn what photography’s inner language was, I might be able to make a book of images that I could put together. I was so fortunate in 1963 to meet Henri Cartier-Bresson on the streets of Manhattan and he took me and Tony Ray Jones, my shooting partner, out for coffee after we all photographed the St. Patty’s Day parade. So to meet Cartier-Bresson when I was 25 years old and to sit and talk with the master and to hear him talk about photography was one of those turning points that just spins your life out of control. Garry, I just met on the street and we became very intimate friends, and I met Diane Arbus on the street and Lee Friedlander. Over the years these were connections that allowed us to have conversations in our humble way, and it was only with John Szarkowski, who was the curator at MoMa and who basically changed the face of modern photography by making shows and writing books and being the most eloquent speaker about photography that there has ever been in the medium. I am so grateful to John for showing me that you can actually engage your ideas and find a language for them and talk about the medium without having to explain it to everybody, but just talk about the strength and poetics and beauty of this form and speculate, because that’s what John was, he was a socratic speculator and could bring arguments and playfulness into the dialogue about photography. I feel that these people were my mentors in the sense that we engaged in ideas and there was work to look at. That’s a great benefit.

Street photography. What do you think makes street photography so appealing to the viewers? Can you define street photography because for me, not all photographs taken on the street can be under this umbrella of ‘street photography’. I think this is a specific genre of photography that has to be approached in that way, would you agree?

I do agree. I think there’s a lot of crap out there today that people say, ‘oh, street photography’ and that they’re basically making portraits or objects on the street. There isn’t the same kind of critical engagement with the many facets of the street that draw the best out of some street photographers. I think street photography requires a consciousness of the moment that you see unfolding in front of you. Some special sixth sense or extrasensory perception about the way things are manifesting on the street ahead of you. Maybe 20 or 30 feet ahead of you. You see enough things on the street happening and you know that in about 10 seconds or less, you’re going to be in the mix, the mashup, let’s call it a mashup, that’s what street photography is. It’s a lot of things happening simultaneously and only certain kinds of visualizers; street photographers can recognize the potential of these various actions coming towards them at any given moment. The potential of them to manifest as an image, comes from them being read as the invisible text of the street. So if you can think of it as a text, and see it all happening in front of you, and you know if you step to the right, or left, you’ll be in position to capture or describe this mashup , then you are thinking like a street photographer. Colin Westerbeck and I wrote the book ‘Bystander: the history of street photography’ and we researched all the way back to the dawn of photography to see that this very same issue was always alive in the minds of even the earliest photographers who didn’t have the equipment, that could handle the speed of things and yet they tried to make something out of life on the street. Because, to tell you the truth, every other genre of photography, the landscape, the portrait, the still life, all of them come from, or have a relation to the history of painting, but only the photographs of the street were new. Painting never saw anything like that before; with things cut off at the edge of the frame, fragmentary things happening all over. So photography was born on the street. That’s its essential nature. And I thought that by examining this and writing this book Bystander, we would be able to bring street photography into the argument in art so that we could value it, but value it for the profundity of meaning and poetry and culture that it represents. I think street photography stands at the center of the photographic act.

You end the book with a still life from 1964 calling it back then “The nature of time: First Still Life”. It ties back to the images you are creating now and in some way give them a new context as if you were always meant to make them, just not back in the 60’s. Can you talk about the concept of having this photo close the book? And how does it tie with the concept of having the book run from your recent years to the very early stages of your career.

Two years ago we were in the process of selling 35,000 vintage prints to a collector in New York and going through the archive, and at the same time I was beginning to prepare this book and by the time we finished assembling and organizing the archive, we discovered this picture and I realized, Oh my God, I did that, 50 some-odd years ago because someone had given me an advertising job and so I took some stuff that was around the apartment and I put it on the radiator by the window sill on an angle so that I could use window light to light it. I remember, I walked around the house looking at objects that I had, pieces of dried fruit and a sunflower and a clock, some of these things were just there, and so I kind of tried to make a Dutch still life, to give each thing in the picture, some kind of meaning for myself just so that I would have a reason to make the picture.

I don’t think of it as profound or of really of any great significance, but for me at the time I made a little list of them so that I could justify using them. It seemed like a perfect book end for the book. And that’s really, the justification because for many years I had said I never made a still life, and now I’m caught in my own false hood because I obviously did make that still live, and now when I look at it, I realized, hey, it’s not so far from what it is that I’m doing now, except I didn’t have all the experience in the middle.

I am sure there are many young artists, and myself included, that would love to hear your absolute most important tip you can give young artists?

Well, I probably gave that tip already in some of what I’ve said, but this is what I find of everlasting importance to me and the thing that I turn to whenever I lose my sense of self or I lose my way or I’m distracted, because after all, we are living in an age of incredible distraction. The great merchandising energy of the Internet has hooked us into being distracted every 30 seconds to look at our phone or device to check in, so we can hardly have a kind of meditative thought pattern without jumping to see what message has just come to us, and what anybody could sell us on that messaging application. So I think that consciousness, and following your instinct is of utmost importance, and particularly in photography, because photography deals with time. You have a camera with a dial on it that says a thousandth of a second, or a five thousandth of a second, it’s like it’s a time machine and our observations and our consciousness comes up exquisitely fast and disappears in the same fraction of a second. And I think that learning how to attend to your own consciousness, how to either provoke it, or be in a position to observe what it is – because if you look in the field in front of you – you’ve got a 90 degree sweep that is your active field of observation. What’s happening out there? And if you get the slightest intuition that this cluster of people, or this object, or this place, or this shadow, or this moment is unfolding in a way that moves you, then you must address that, precisely at that moment without hesitation, without a second thought, just make yourself respond at that moment.It is in that flicker of recognition that the germ of our art instinct is born and by following that, it will allow you to become stronger and more decisive. No matter what your art form is, if you follow that tiniest of Zen bells when it goes off, it will be louder than anything else in the field that you’re looking at, and you must follow that if you want to find your way.

Thank you, Joel.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Earth Week: Hugh Kretschmer: Plastic “Waves”April 24th, 2024

-

Earth Week: Richard Lloyd Lewis: Abiogenesis, My Home, Our HomeApril 23rd, 2024

-

Earth Month Photographers on Photographers: Jason Lindsey in Conversation with Areca RoeApril 21st, 2024

-

Earth Month Photographers on Photographers: J Wren Supak in Conversation with Ryan ParkerApril 20th, 2024

-

Earth Month Photographers on Photographers: Josh Hobson in Conversation with Kes EfstathiouApril 19th, 2024