Photographers on Photographers: Kevin J. Miyazaki on Emily Shur

For the entire month of August, photographers will be interviewing photographers–sharing image makers who have inspired them, who they are curious about, whose work has impacted them in some way. I am so grateful to all the participants for their efforts, talents, and time. -Aline Smithson

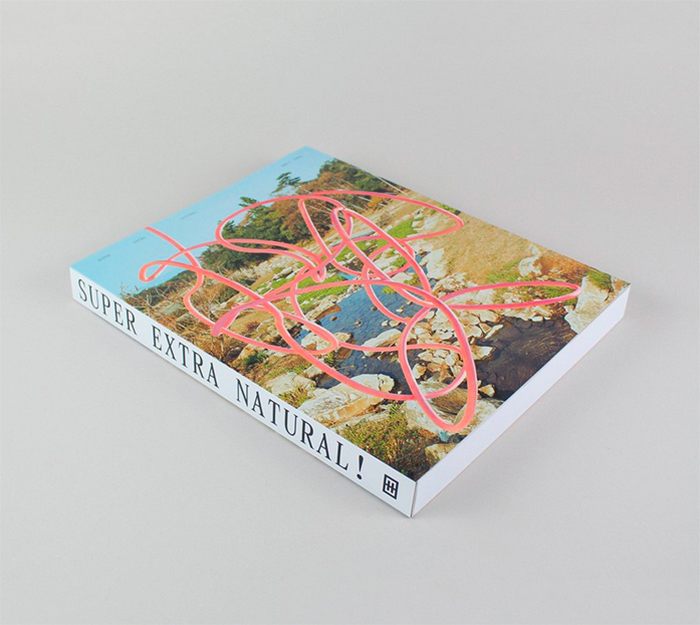

Make no mistake, Emily Shur’s book of photographs from Japan, Super Extra Natural!, is not filled with travel pictures. They may have been shot in a faraway place, but where travel photographs are successful in presenting easily understood imagery, Emily’s pictures are curious and open ended. They are not Lonely Planet’s Japan, but rather the Japan you find when you walk 8 kilometers in one day, quietly looking around each corner.

I first knew of Emily through her wonderful editorial and commercial work, which jumps off pages and is bright in both concept and execution. Her range as a photographer is impressive: she can photograph Will Ferrell and a dog (and an ice cream cone) one day and a napping Japanese shop cat on the next. I wanted to talk with Emily about her book and work from Japan because I think we both share a love of the country, and from views as outsiders of different sorts.

Kevin J. Miyazaki is a photographer based in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. A recent DNA test shows him to be 93% Japanese and yet he can’t speak 93 words of his ancestral language. He was born and raised in the suburban Midwest and his artwork addresses themes of ethnicity, memory and family history. His photographs have been included in exhibitions at the Center for Photography at Woodstock, The Griffin Museum of Photography, The Haggerty Museum of Art and Newspace Center for Photography. His editorial work is represented by Redux Pictures and recent clients include The New York Times, Food Network Magazine, Smithsonian, AARP and Architectural Digest.

Emily Shur: Now based in Los Angeles, Emily was born in New York City to an auditorium full of nursing students and grew up in Houston, Texas. Her original style connects her diverse portfolio, mixing vibrant color and personality with strong conceptual storytelling. Whether shooting portraits of well-known celebrities and athletes, fashion spreads for top designers, or personal projects, Emily’s work celebrates unique characters and a singular point of view. Her client list—including HBO, Amazon, Netflix, Sprite, Chrysler, Dodge, Alaska Airlines, KFC, Samsung, Booking.com, Nike, Adidas, Universal Pictures, NBC, CBS, Hulu, FOX, Toyota, Sprint, and American Express—matches her diversity. Emily won The Art Director’s Club Young Guns global competition early in her career, which led to her work being exhibited as part of the Taylor Wessing Portrait Prize exhibition at London’s National Portrait Gallery and Humble Art’s 31 Women in Art Photography exhibition. Her images have been published in various collections including Milk and Honey: Contemporary Art in California, Photographers’ Sketchbooks, and eight editions of American Photography. In the fall of 2017, Kehrer Verlag published Emily’s first monograph, Super Extra Natural!, chronicling twelve years of travels in Japan.

Statement for Super Extra Natural!

I can remember taking all of the photographs in this book, and when I say that, I mean that I remember actually pressing the shutter down for that precise fraction of a second. I remember the where, the when, and the why. I remember the sounds, the weather, how I felt right before and right after that moment. I remember wanting to preserve what was around me in a way that would serve as an accurate representation of my feelings; the way an old song or a smell can transport you to a specific time and place.

Between 2004 and 2016 I made a total of 16 trips to Japan with no agenda other than to see. It was clear from the start that I had found my place: a country whose natural beauty is accentuated by thoughtful design, a culture that values simplicity and kindness, yet also embraces the completely absurd. These images were made on my daily walks and wanderings; stopping to photograph what speaks to me in that moment. The majority of my Japan trips so far have been adventurous and freeing, but there have also been some that felt strained and tiresome. Inevitably the camera strap gets heavy, and I begin shifting the weight from one shoulder to the other and back again. Maintaining the intoxication of seeing anything with fresh eyes eventually becomes its own challenge. What began as an exploration of an unknown place has evolved into an exploration of my own perspective on photography and the act of taking photographs. The place absolutely informs and affects the images, but the images are not about a place. They’re about a state of mind.

There have been times I’ve wandered all day without taking a single picture. I’ve walked for hours only to realize I’m lost and nowhere near where I intended to be. I’ve made long and complicated excursions to remote areas I assumed would be photographic paradises, only to feel exhausted and frustrated. Nothing speaks to me. The thought of no longer being inspired is terrifying. My head starts to fill with anxiety about my mindset and how it could affect the rest of the experience. I worry about how much I worry.

Eventually I learned to surrender to and embrace the unexpected. What I thought would be interesting sometimes wasn’t, but some of my favorite images in this book were taken because I went the wrong way or got lost. Instead of being constrained by expectations and potential disappointment, the process of making these photographs has become an exercise in letting go. Walk another block. Turn left instead of right. Explore and be open.

If the experience of taking pictures could be likened to an orchestra, each part of the experience would be an instrument making its own individual sound. Light is one instrument. Color is an instrument. Body language or movement is another. Shapes are another and so on. Of course there are also non-visual elements in the orchestration of a photograph. These are usually more difficult to articulate, but in many ways are the defining characteristics of a meaningful image. The moment in which there is perfect harmony amongst all the instruments is the moment when a worthwhile photograph is made.

Being able to recognize that harmony of the physical and the emotional, the tangible and intangible, occurring in plain sight for that fleeting instance is a sensation beyond photographic satisfaction. Shapes and colors seem to fill the frame as nature intended. There’s no questioning. It is correct. It feels like an affirmation of life’s richness, as if the universe is quietly trying to tell me something: I am in the right place, doing the right thing, and in that moment, I feel truly grateful.

In the past I’ve tried to separate my opinion of the photograph from the experience of making it. I worried the two might cloud one another. Pictures taken on a spectacular day aren’t necessarily spectacular images and vice versa. Only the photographer knows the specific circumstances that surround their photographic decisions. The viewer sees just what we show them, not the before or the after, nor what’s outside of the frame. They don’t see our struggles or our elation.

Or do they?

What I’ve come to understand and accept is that those intangible pieces of the orchestra, the non-visual elements of a picture, are heard as clearly in the harmony of an image as the conventional fundamental photographic elements. The final image is as much how and why the photographer came to be in that particular situation, as it is their aesthetic point of view. As Edward Steichen said, “Once you really commence to see things, then you really commence to feel things.” – Emily Shur

Kevin Miyazaki: What brought you to Japan the very first time?

Emily Shur: I first tagged along on a trip with my parents in 2004. My Dad was invited to give a talk about his work (he’s now retired but at the time was a research scientist). He and my mom had been before and thought I would enjoy Japan. I think I was 28 at the time, and I had never been anywhere in Asia or anywhere like Japan.

We spent half of the time in larger cities – Tokyo and Osaka – and the other half where my Dad’s meeting was taking place which was a small town in a fairly off-the-beaten-path part of Japan (especially for non-Japanese people) called Ise-Shima. It wasn’t the sort of place an American family would normally go on their first trip. I loved both the cities and the rural areas equally, and that trip was such a great introduction to the country. Even now, I still plan my trips to include some city time and some middle-of-nowhere time.

KM: Do your very first pictures from Japan differ from the very latest?

ES: In some ways yes, and in some ways no. I think that’s one of the reasons I haven’t lost interest in photographing there. There are images in the book from my very first trip in 2004 that I still really love (one of the images that makes up the cover of the book is from 2004), and I was there this past January and took some new images that I really love.

In between then and now, I’ve had trips where I come back with one good image, twenty good images, and sometimes no good images. I’ve been surprised more than once in terms of what I wind up gravitating towards photographically.

I’d say my pictures from Japan have changed in the same ways that all of my pictures have changed in the last 14 years. I’m still me, still with the same eye, but I’d like to think that my images have been fine-tuned. I’m less interested in photographing pretty places or pretty people just for the sake of pretty pictures. I’m more interested in some subtext, some mood, some emotional connection. Pretty is not bad…a lot of my pictures from Japan are of places and things that are indisputably pretty, but I’ve tried to be careful in my editing to exclude pictures that have no soul.

KM: What are three words that describe your feelings for Japan?

ES: Natural, Peaceful, Inspiring.

KM: Three words that describe your feelings of the U.S. right now?

ES: Frightening, Familiar, Confusing.

KM: There seems to be so much about Japan to figure out: old customs, small gestures, big ideas, all just below the surface. What’s something you’ve yet to figure out?

ES: I have to say I can get by pretty well at this point on all cultural fronts with exception to speaking the language. That’s still my weak point, and I know if I could even get to a conversational point with my Japanese, it would most likely change my time there.

In terms of customs, norms, logistics, traveling, etc., my rule of thumb has been if I don’t know what to do in any given situation, I err on the side of being polite and humble. You can’t really go wrong with that. Although, I know that if I could speak some Japanese, it would make my experience there much richer. I’ve made minor attempts at learning online and listening to tutorials in my headphones when I’m there, but not much has stuck beyond a couple phrases.

KM: Anywhere in the world, when I have my camera, I look like a Japanese tourist. In Japan, I can’t really figure out who I look like. Who do you look like while working there?

ES: I think I look like an outsider taking pictures, and I can’t get around that. I’ve made a concerted effort to be respectful in my picture taking, and one thing I do have going for me is that photography, as an all-around activity, is widely respected and very popular in Japan. I see lots of people, who for the most part seem to be hobbyists and serious amateurs, who take their picture-taking very seriously.

It’s not uncommon to go to a park on any given day and see a row of cameras on tripods with a small group of people behind them, waiting for the right moment, talking, socializing. It’s different than say, in LA, where I might get some skeptical looks or asked if I have a permit to shoot. There are a ton of camera stores and book stores – big and small. Film is alive and well. I’ve even gotten some nods of approval when people take a look at my camera. So, in Japan, I’m definitely a tourist, but I’ve never been made to feel as though I’m doing anything wrong by taking pictures.

KM: Do you think of this work is a reaction against your commercial work?

ES: No, I have taken pictures like these for as long as I have been taking pictures. I just wound up making a living doing a different type of work. My commercial work affords me the ability to dedicate time to this work, publish a book, travel, etc. I’ve had all kinds of feelings about being a commercial photographer and trying to find a balance between the pictures I take for work and the pictures I take for myself. Ultimately I’m proud of both sides of my work.

The commercial work doesn’t come without its set of difficulties…there’s a lot of stress, rejection, spinning wheels, dealing with stuff that has very little to do with photography, etc. So, I do think it’s very important for me to set aside time to enjoy photography. That could be anything from shooting in a way that is pleasurable and peaceful for me to simply taking the time to work on those images and do something with them.

KM: I’m a bit obsessed with Japanese handkerchiefs and now hunt them down while I’m there. What’s in your suitcase on your return trips?

ES: Oh this is an easy one – socks!!

KM: If you’d allow me one gear question (sorry): When I look at your pictures, I seem to want to visualize you making them. Maybe it’s because many are quiet and unobtrusive, but delicately composed. What’s your camera of choice for this work?

ES: I’ve shot the same camera body and one of three lenses on every single trip. I use a Mamiya 7II body with an 80mm lens about 75% of the time. Every once in a while I throw a 65mm or 150mm lens into the mix as well. I don’t bring a tripod or any lighting. I shoot everything handheld with available light, and purposefully keep my camera set up lightweight so that it doesn’t become a burden when I’m out all day walking around.

KM: Do you think you could ever live in Japan? I understand it’s a hard culture to deeply assimilate into. Would the place hold the same wonder to you if you weren’t a visitor?

ES: I’ve thought about this a lot, and my husband and I have fantasized about moving there, but I definitely think living there would be a much different experience than visiting. I would love to take an extended trip there – a month or two, maybe even a year – but ideally I’d dedicate that time to my own work instead of trying to make a living there.

For a few years I tried to get work in conjunction with my travels, and I have shot a couple jobs there (mostly for non-Japanese clients). I’d happily take more assignments there, but I get the feeling that trying to navigate the world of being a working photographer in Japan as a non-Japanese person would be difficult. I love taking pictures there so much; it would be very sad to me if I lost that feeling because I was trying to fix something that wasn’t broken in the first place.

KM: I know you just moved to a new space in L.A. this week. If money and availability were no object, what’s one photograph (by any photographer living or dead) that you’d love to hang on your wall?

ES: Ooohhh…great question. There are so many! I actually have invested in or been gifted many great pieces by some of my favorite photographers like Mary Ellen Mark, Takashi Homma, and Simen Johan. (My husband has great taste when it comes to birthday gifts.)

Going with an image I love by a photographer I don’t yet have anything by, the first photograph that comes to mind is Outdoor Dining, Bonneville Salt Flats, Utah, 1992 by Richard Misrach. This image is on the cover of the edition of my Desert Cantos book, which was one of the first photo books I ever bought…actually it’s more likely that my parents bought it for me since I’ve had it since high school. That book/body of work really had an impact on me as it showed the landscape in its natural state, but because of Misrach’s choices, the images take on an almost surreal quality. Each image is special. It’s like an album of only great songs; no filler. I always want to be purposeful in my picture taking so I wouldn’t mind looking at that image everyday as a reminder.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

McCall Hollister in Conversation With Douglas BreaultMarch 6th, 2026

-

Olga Fried: Intangible EncountersFebruary 18th, 2026

-

Anne McDonald: Self-PortraitsFebruary 17th, 2026

-

Richard Koenig: Field Notes: View from a Hotel WindowFebruary 13th, 2026

-

Beyond the Photograph: Editioning Photographic WorkJanuary 24th, 2026