Photographers on Photographers: Lori Nix and Rose DeSiano

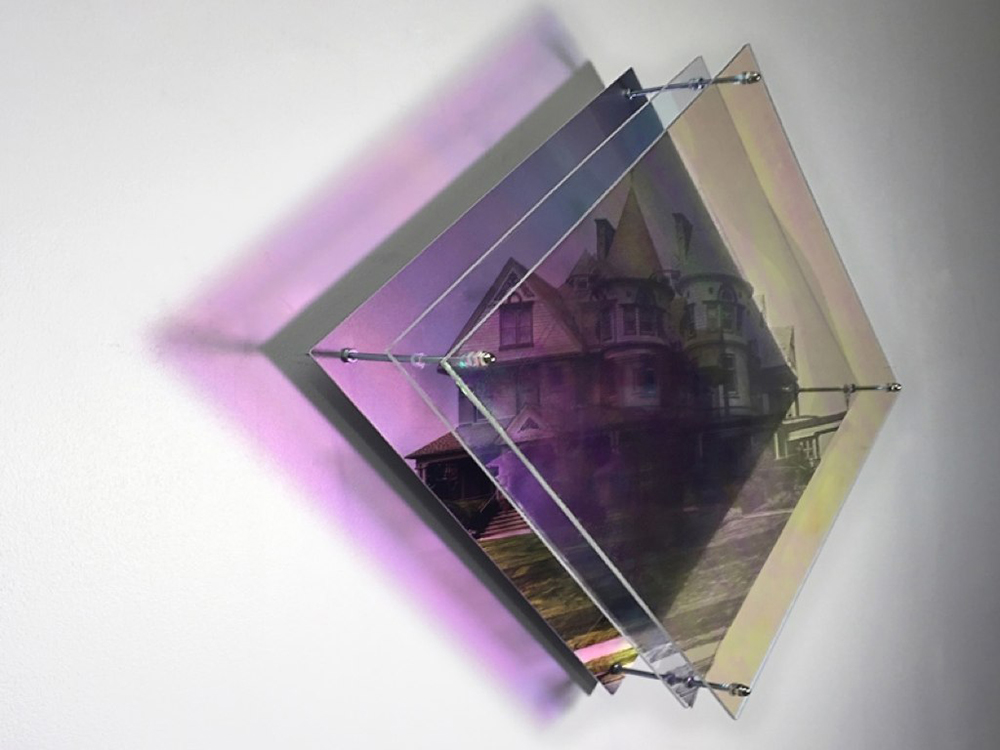

©Rose DeSiano, “Absent Monuments“, winner of the 2018-19 UNIQLO Park Expressions Grant is on view at Rufus King Park Jamaica, Queens now through July 2019

For the entire month of August, photographers will be interviewing photographers–image makers who have inspired them, who they are curious about, whose work has impacted them in some way. I am so grateful to all the participants for their efforts, talents, and time. -Aline Smithson

Kathleen and I have been fans of Rose DeSiano’s photography for many years.

Working with 3-D scenes ourselves, we lover her use of unconventional materials and sculptural forms in the construction of her photographic objects. These dimensional forms are exciting and really complement her imagery. Rose’s work is complex, thoughtful, and raises important questions about how we look at art and ultimately, how we look at our collective history and mythology. With her return to making large-scale public art, her composited and manipulated images literally give viewers a fresh, new perspective on the world.

Her site-specific installation, Absent Monuments, will be on view at the Rufus King Park in Queens this summer as part of the Uniqlo 2018 Expression Grant for Public Art.

Lori Nix and Kathleen Gerber have been making art collaboratively for many years. Based in Brooklyn, they construct meticulously detailed model environments and photograph the results. For the last decade they have found inspiration in their urban surroundings, imagining a future mysteriously devoid of mankind.

Lori Nix and Kathleen Gerber have been making art collaboratively for many years. Based in Brooklyn, they construct meticulously detailed model environments and photograph the results. For the last decade they have found inspiration in their urban surroundings, imagining a future mysteriously devoid of mankind.

They have exhibited across the United States and internationally, with exhibitions at ClampArt Gallery in New York City, the George Eastman House, The Toledo Museum of Art, Catherine Edelman Gallery in Chicago, Paci Contemporary in Italy, and Galerie Klüser in Germany. Lori is a Guggenheim Fellowship recipient in Photography for 2014.

Rose DeSiano uses alternative photographic processes, sculpture and manipulated photography as tools to examine cultural symbolism, the collective consciousness and the long, tangled history of the photograph as both a truth teller and mythmaker.

Her work has been exhibited in New York solo gallery shows, throughout the North East and West coast, and Europe: including museum exhibitions and biennial’s; Bronx Art Museum, NY, Allentown Museum of Art, PA, Heritage Museum of Malaga, Spain; international photo fairs such as Photoville NYC, FOTOFOCUS, Ohio and Orange Changsha Photo Festival, China.

Engaged in a public art practice, her artwork has been commissioned by Port of San Diego, CA, I-Park, CT, NYC Dept. of Parks & Recreation’s Central Park, Randall’s Island, and Rufus King Park. Most recently, her she unveiled a large public arts photo-sculpture in NYC, winner of the 2018-19 Uniqlo Parks Expression Grant.

DeSiano is a graduate of the BFA New York University’s Tisch School of Arts, Photo & Imagining Department (2001), and her MFA from the Art Center College of Design, Los Angeles (2005). She is currently a Professor of Photography at Kutztown University, PA, while living and working in Brooklyn, NY.

©Rose DeSiano, “Absent Monuments“, winner of the 2018-19 UNIQLO Park Expressions Grant is on view at Rufus King Park Jamaica, Queens now through July 2019

Lori Nix/Kathleen Gerber: Do you consider yourself a photographer? Explain your work

Rose DeSiano: I consider myself a photographer because the image remains the most important element of my artwork. The sculptural form and materials are there to boost the power of the photographic image or to recontextualize it’s meaning— but the object and the materiality remain secondary. My photography regularly deals with the marking of cultural history in our landscapes and the way in which we choose to present our culture in visual constructs such as landmarks, reenactments, monuments and museums and of course photographs. In my latest piece “Absent Monuments”, winner of the UNIQLO Park Expressions Grant currently installed in Rufus King Park, Jamaica Queens is a set of four, fifteen’ foot tall mirrored obelisks. Their plinth bases feature photographic-composite scenes representing the landscape’s complex history of colonization, war, Native Americans, abolitionism, immigration, suffragist and rural urbanization, all presented using in blue and whites in Dutch Delft tiles. Sounds like sculpture, maybe? but it functions within the language of photography.

©Rose DeSiano, “Absent Monuments“, winner of the 2018-19 UNIQLO Park Expressions Grant is on view at Rufus King Park Jamaica, Queens now through July 2019

©Rose DeSiano, “Absent Monuments“, winner of the 2018-19 UNIQLO Park Expressions Grant is on view at Rufus King Park Jamaica, Queens now through July 2019

LN/KG: Explain for people who are unaware of your work.

RD: I started out making traditional photographic prints very much in the vain of the ‘New Topographics’ movement but felt limited by the finite nature of the print. I started creating heavily complex photo-composites, at this point I was interested in how you could make a singular composition from multiples; one that looked unified but possessed distorted depth and scale — it was all about optical manipulation…the seamless merging of disparate parts. Ultimately, I abandoned paper print and became interested in how alternative substrates changed the meaning of the photographic imagery. That’s how it started, and things remained flat for a while.

In 2012, I had an exhibition “A War Imagined” of photo-tapestries, woven jacquard fabrics. The imagery was the priority for me, I had been photographing WWII and Vietnam War reenactments in the United States, and I was using the tapestries to talk about the history of myth-making and role of photography in war mythology. The material came secondary to the vision of my photographs. That’s how I view all of my usage of alternative photo-presentations, which are now not only substrates but actually three-dimensional objects — they are a secondary supporting role to the photograph.

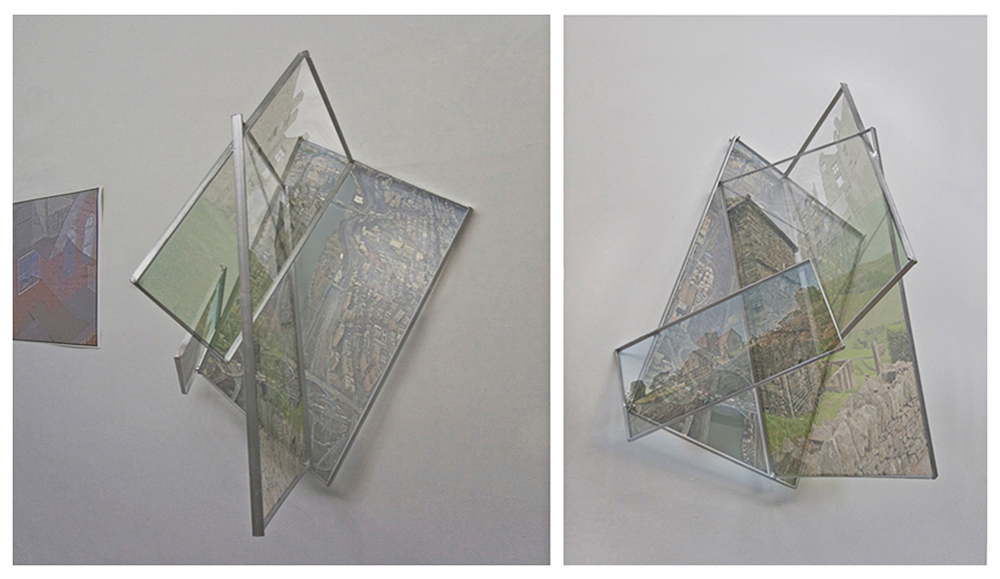

©Rose DeSiano, “Island of Empirical Data and Other Fabrications” an NYC Dept. of Parks installation on Randall’s Island 2017-18

©Rose DeSiano, “Island of Empirical Data and Other Fabrications” an NYC Dept. of Parks installation on Randall’s Island 2017-18

©Rose DeSiano, “Island of Empirical Data and Other Fabrications” an NYC Dept. of Parks installation on Randall’s Island 2017-18

©Rose DeSiano, “Island of Empirical Data and Other Fabrications” an NYC Dept. of Parks installation on Randall’s Island 2017-18

LN/KG: Materials or just forms?

RD: Materials and sculptural forms. Again, this is when I go back to my beginnings as a film photographer… I use a lot of transparent materials, things that have luminosity and reflectivity built into them, substrates like mirrors or printing on layered glass or iridescent plexi, it’s really just an interest in the way light works, in optics and visual perception you know its…” painting with light”. It is all same dialogue for me…photography. I then recognized that these materials could also bring a level of… and I’m hesitant to use the word “interactivity” or maybe better “viewership participation” to the work in a way photographic prints can’t — thinking of viewer experiences like Rothko’s Chapel bathing his viewer in color or Anish Kapoor’s luminous enveloping sculptures.

©Rose DeSiano, “Island of Empirical Data and Other Fabrications” an NYC Dept. of Parks installation on Randall’s Island 2017-18

©Rose DeSiano, “Island of Empirical Data and Other Fabrications” an NYC Dept. of Parks installation on Randall’s Island 2017-18

©Rose DeSiano, “Island of Empirical Data and Other Fabrications” an NYC Dept. of Parks installation on Randall’s Island 2017-18

LN/KG: How do you fund your work these days?

RD: I accidentally fell upon a practice that is working for me financially — which is shocking, I have done a couple of public artworks in the past two years. I did my first one ten years ago, out in California, in San Diego, and then I didn’t’work on public works for a long time, Now, I’m interested in it again for two reasons; I realize the scale of which you can work outside is enormous, and this is a real thrill for me after being confined by the limitations of photographic print for so long. I also really enjoy the work being interpreted by people who are not trained to interpret artwork. Its’something I thrive off of, fueling my creative processes — so public artwork has been good. Also, with public artworks, you basically apply with a bid and they fund it in advance, so it’s more of a commission and it cuts out the stress of not knowing if the work will sell.

©Rose DeSiano, “Olmsted’s of Empirical Data and Other Fabrications” in Central Park, part of “It’s Happening! 50 Years of Public Art in the Parks

©Rose DeSiano, “Olmsted’s of Empirical Data and Other Fabrications” in Central Park, part of “It’s Happening! 50 Years of Public Art in the Parks

LN/KG: What defines success for you?

RD: My definition is a work in progress. I think one’s idea of success should always be evolving.

LN/KG: Does that term even really apply?

RD: No. If you start thinking in terms of success and failure you’re bound to stop making work. I don’t sit around thinking about whether or not I’m successful… I think about whether or not if the work is successful! — that’s about the extent of my thoughts about success. Otherwise, you would just freeze yourself in your tracks.

©Rose DeSiano, “Pentaptych Predella” part of her “Empirical Data and Other Fabrication” series at the Allentown Art Museum, Pennsylvania

©Rose DeSiano, “Pentaptych Predella” part of her “Empirical Data and Other Fabrication” series at the Allentown Art Museum, Pennsylvania

©Rose DeSiano, “Predella Legend Keys #2” part of her “Empirical Data and Other Fabrication” series at the Allentown Art Museum, Pennsylvania

LN/KG: Do you have any major influences in your work? At this point? Especially with the public work?

RD: Tons, not all contemporary and not all photographers. I spend a lot of time with photo-archives, from W. Eugene Smith and the FSA to William Eggleston’s books. I think a lot about how the photograph functions…so I look at artists like Penelope Umbrico, Lori Novak, Christopher Williams and how the image is made so of course I Iook at both your constructed photographic-realities — it was my fandom that allowed us to meet [laughs].

Now, that I’m making public works, I recognize how long I have been a fan of public art, not even consciously, which is one of the great things about public artwork. It can be a subconscious enjoyment, you come upon it during your day and you experience it. I grew up with Tom Otterness’s odd brass characters and Bill Brand’s fantastical Zoetrope installed off the D train in Brooklyn (which is now the Q train), I remember being mesmerized by it. It was defunct for over 20 years. I was so excited when they relaunched it. It was then I recognized I’ve always been interested in public art, well before I was trained as an artist. Now, I am looking at gallery artist that also work in public spaces; like Rachel Whiteread’s ability to re-contextualize banal forms into monuments or Olafur Eliasson’s optical wonderments.

LN/KG: What’s next for you?

RD: I would like to try for more commissions and public artworks and possibly make some larger photo-sculptural works in indoor spaces. It would be nice to not have to worry about weather or graffiti as part of my creative process!

©Rose DeSiano, “Domestic Fragmentations” on exhibit at A.I.R. Gallery’s 8th Biennial, DUMBO, New York

LN/KG: What is your definition of a perfect day?

RD: Ha, that’s funny. Is it wrong to answer with Lou Reed lyrics? ‘Perfect Day’ is actually my wedding song. A truly perfect day would be a day in which I don’t have to worry about dashing out of my studio to my next appointment, not for work or friends. A day when I’m not blocking out my life in one or two hour increments. I seem to be beholden to the clock these days.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Nathan Bolton in Conversation with Douglas BreaultJanuary 3rd, 2026

-

Salua Ares: Absense as FormNovember 29th, 2025

-

Ricardo Miguel Hernández: When the memory turns to dust and Beyond PainNovember 28th, 2025

-

Pamela Landau Connolly: Columbus DriveNovember 26th, 2025