Photographers on Photographers: Amanda Dahlgren on Nina Katchadourian

Lavatory Self-Portraits in the Flemish Style, 2012. (“Seat Assignment” project, 2010–ongoing). Courtesy of the artist and Catharine Clark Gallery.

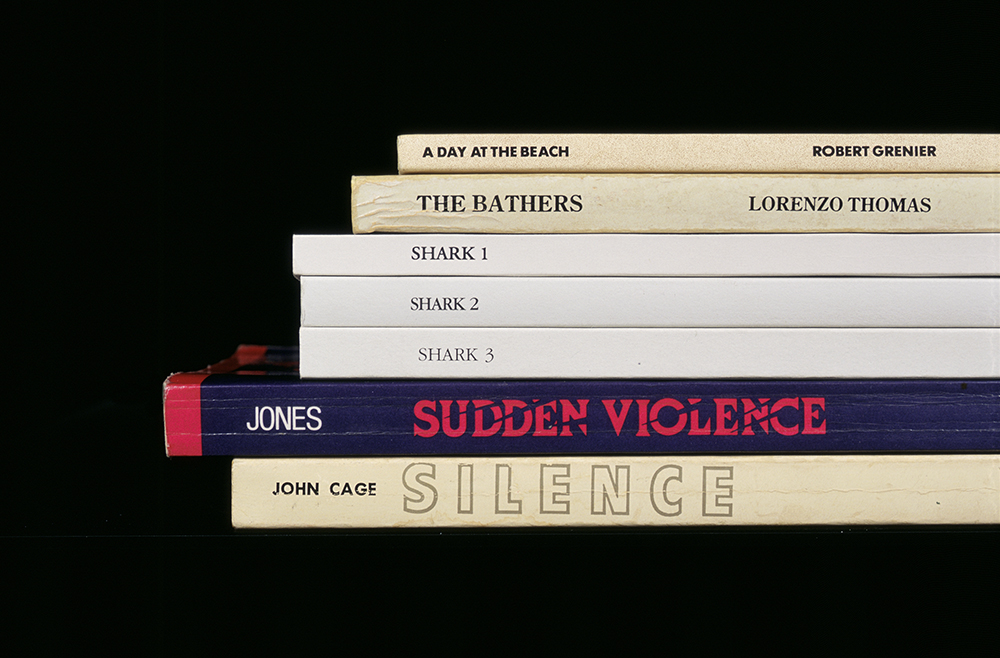

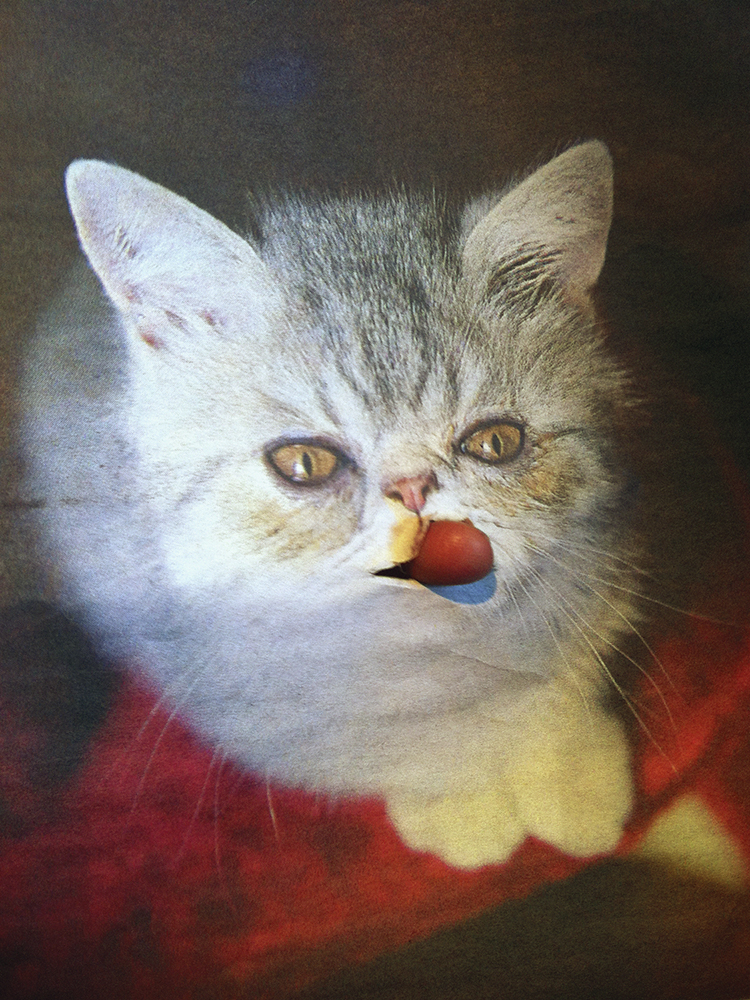

I believe the best artists are those who defy labels and conventions—making work that is compelling and uniquely theirs—and Nina Katchadourian optimizes this idea. Using photography, video, sculpture, performance, and collaboration, she finds wildly creative ways to show us the magic that is all around us. In her ongoing Seat Assignment project, for example, she transforms the mind-numbing tedium of air travel into opportunities to play: reimagining herself as the muse to a Flemish painter, using her seatbelt buckle to create fantastical compositions, and juxtaposing appropriated imagery with found objects to humorous and poignant ends. And for over 25 years (and counting), she has been meticulously combing through private and public libraries, creating work for her Sorted Books project: combining performative strategies with photography to create poetic, funny, and thought-provoking “sentences” out of disparate book titles.

In all her work, she reminds us that art and creativity can (and should) be done anywhere, at any time. As someone who tends to approach my own art practice with a sometimes stifling obsessiveness, it was such a gift to have the opportunity to learn more about Nina’s work and her practice through this interview process. I am tremendously grateful to Nina for her remarkable generosity in sharing her time and wisdom with me and our readers.

A Day at the Beach, from the series Sorting Shark, 2001. (“Sorted Books” project, 1993–ongoing). Courtesy of the artist and Catharine Clark Gallery.

Evil Kitten. (“Seat Assignment” project, 2010–ongoing). Courtesy of the artist and Catharine Clark Gallery.

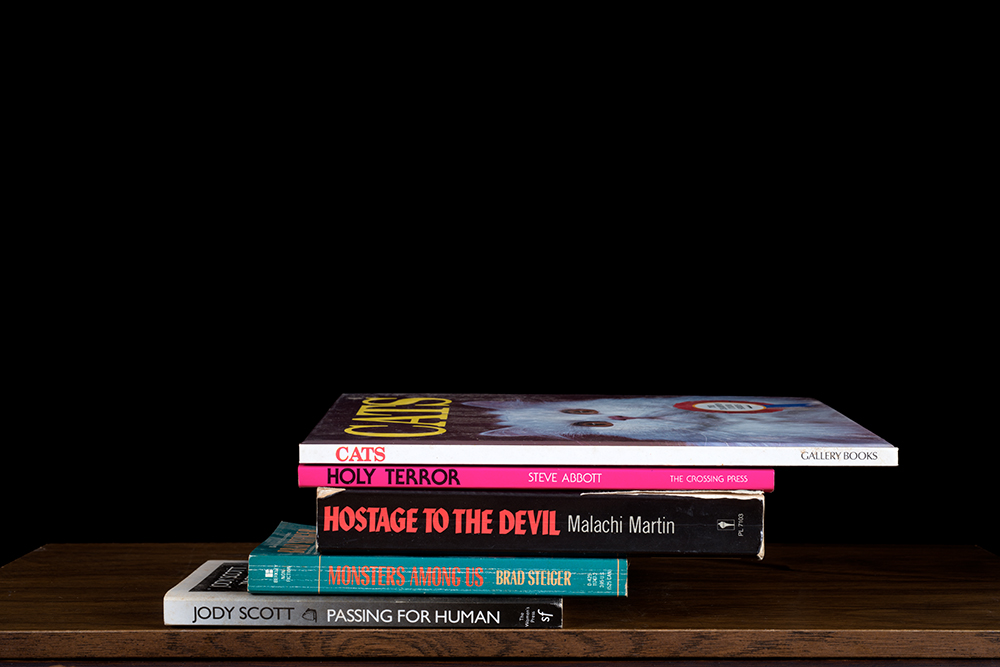

Cats (Holy Terror), from the series Kansas Cut-Up, 2014. (“Sorted Books” project, 1993–ongoing). Courtesy of the artist and Catharine Clark Gallery.

AD: When I share your work with my students, friends, and family, the overwhelming response is delight and yet, there is a level of profundity to your work when one pays attention. How have you navigated this duality to such success in your career, especially in the art world, which seems to often take itself way too seriously?

NK: I’m glad to hear the response you describe, and you are correct to point out a kind of resistance to humor in the art world. I’ve been thinking for a long time about what the cultural expectations are when it comes to art, at least in a European or American context, and I think one of the grand myths is this idea (a rather Romantic idea, I will say) of “timelessness.” There is something interesting about humor to me because it is so “perishable”—it depends so much on social context, on something that might only make sense or be funny for those who are part of a society at a certain moment in time. I’m not sure you can argue that humor is “timeless,” in other words, in the way that art thinks of “timelessness.”

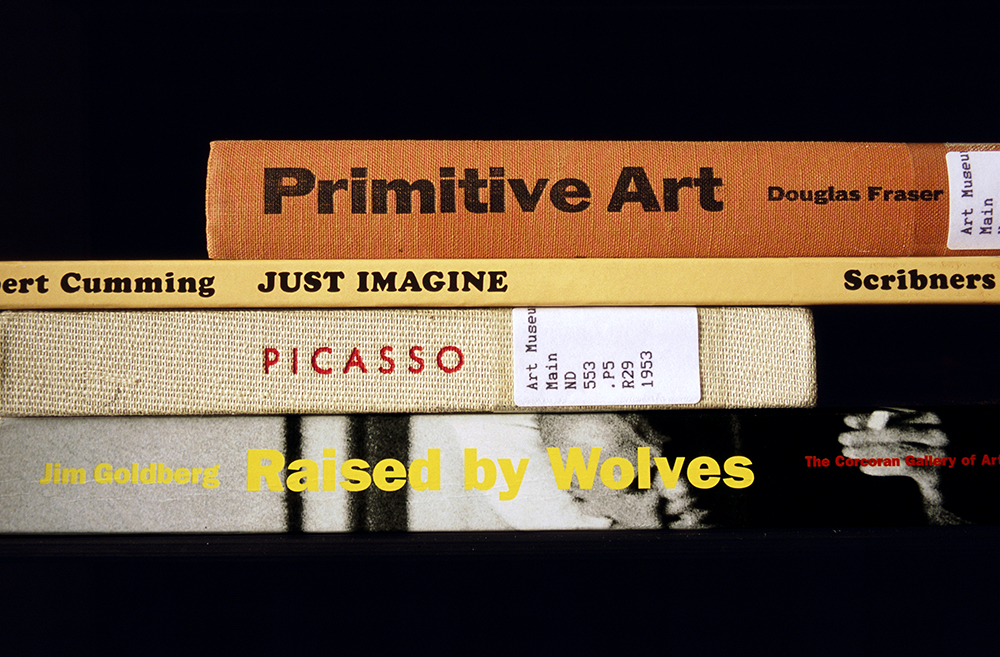

Primitive Art, from the series The Akron Stacks, 2001. (“Sorted Books” project, 1993–ongoing). Courtesy of the artist and Catharine Clark Gallery.

I never make work that is humorous as a goal—in other words, “funny” is not the point, but it seems to be a device that is often one that I use. It brings people close, and invites people in. It’s a good hook. And once hooked, then you can do something else with your viewer’s attention. But it hasn’t always been easy to navigate this for me, and I’m sure that there are instances where my work isn’t taken seriously. I argue again and again that “funny” and “frivolous” are not the same thing. I am utterly uninterested in “quirky” or “whimsical” and I hate those adjectives applied to my work, in fact, because they sound so devoid of intentionality. I think for playfulness or humor to have resonance, and to be effective, they also have to be present alongside great rigor. The union of play and rigor is what I feel I am strongly invested in.

Topiary, 2012. (“Seat Assignment” project, 2010–ongoing). Courtesy of the artist and Catharine Clark Gallery.

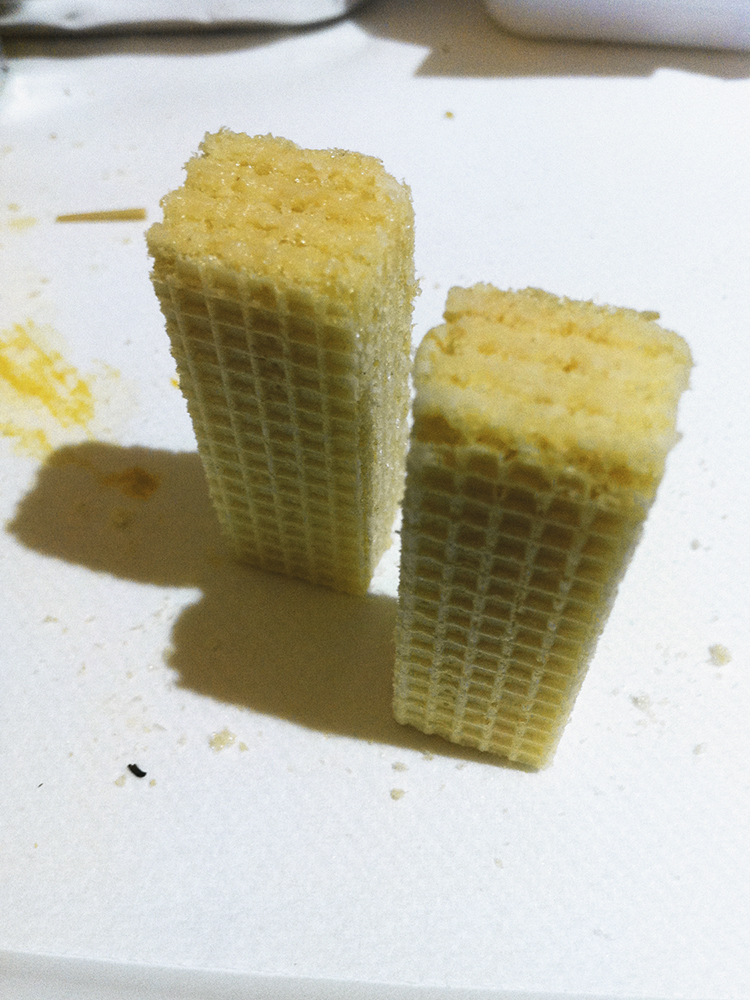

Twin Towers, 2011. (“Seat Assignment” project, 2010–ongoing). Courtesy of the artist and Catharine Clark Gallery.

I saw an interview you did with MoMA in which you talked about your “rules of engagement” for making art (specifically referring to the Seat Assignment series). How do you decide what those will be? Have you ever changed them part-way through after realizing they aren’t working? Have you ever abandoned a project that wasn’t working?

In very general terms, the parameters I often like are ones that constrain or limit me, strange as that may sound. With Seat Assignment, the ongoing question has been something like “What can I make with almost nothing? What can I make under circumstances where art might not seem likely or possible, and where there are all kinds of constraints, ranging from social to physical to material to temporal?” I don’t think it’s as cut and dry as your question sets up, however; it’s not as if I say “Here are the rules!” and issue some kind of decree to myself. It’s more about defining a method of working and sticking to those confines, and seeing where they get me.

Lavatory Self-Portraits in the Flemish Style, 2012. (“Seat Assignment” project, 2010–ongoing). Courtesy of the artist and Catharine Clark Gallery.

Lavatory Self-Portraits in the Flemish Style, 2012. (“Seat Assignment” project, 2010–ongoing). Courtesy of the artist and Catharine Clark Gallery.

Have you had any incidents in making your Seat Assignment work in which your fellow passengers had interesting reactions? For example, I imagine you had to spend quite a bit of time in the bathroom for pieces like the Lavatory Self-Portraits in the Flemish Style and Under Pressure.

When it comes to the works made in the lavatory, I often get asked the question “Wasn’t there a line outside?” Since I made the images on a 14-hour flight from San Francisco to New Zealand, everyone was asleep through long stretches of time. At first I rushed like crazy to do things in a minute or two, but eventually, I realized I could be in the lavatory for 20 minutes at a time with no one outside when I came out. I definitely don’t want to inconvenience anyone! I’ve also been the person waiting endlessly in line… Similarly, the music videos made in the lavatory take exactly as long to make as the song itself, which I would hazard to say might be even less time than many people spend in the lavatory.

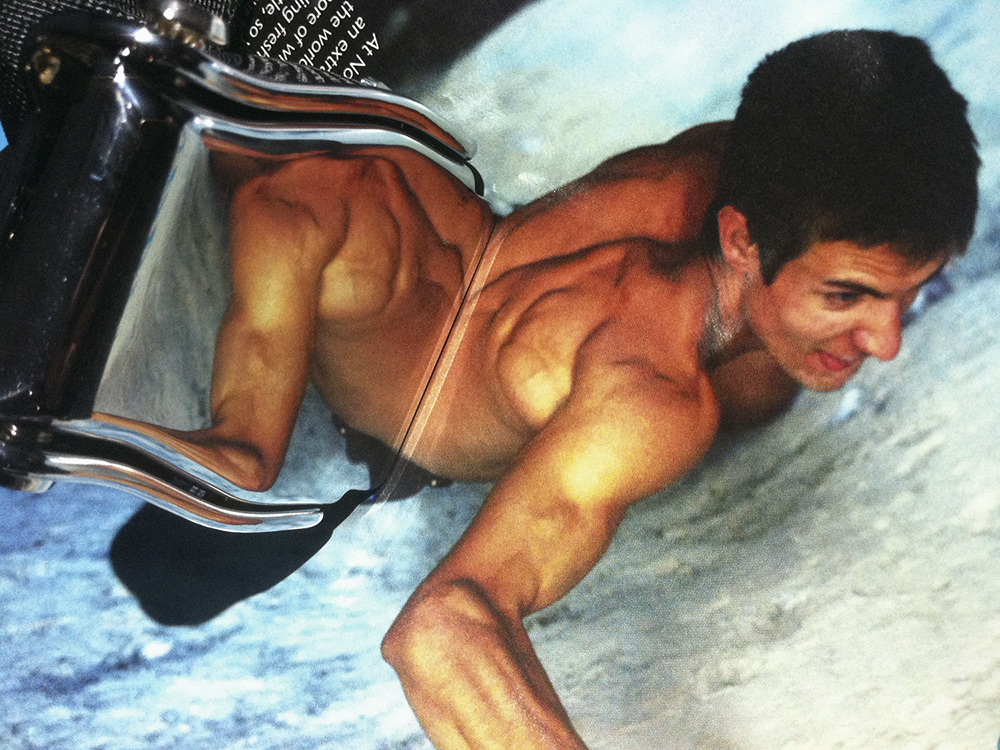

Centaur. (“Seat Assignment” project, 2010–ongoing). Courtesy of the artist and Catharine Clark Gallery.

When I make work on my tray table, which is where most of the project happens, you’d be surprised how infrequently there are questions or reactions. I’d say that over these last eight years of contributing to the project, there have been three or maybe four comments, ever. And that’s a bit depressing to me—people don’t notice, or they simply don’t want to get involved, or they aren’t curious—or they think the whole thing is so strange that they avoid me!

“Accent Elimination,” 2005, Nina Katchadourian from Nina Katchadourian on Vimeo.

I recently re-watched the clips from Accent Elimination and I was struck with the poignancy of the choice to show yourself struggling to speak with your parents’ accents, while they seem to be less frustrated, even laughing at times. Is that accurate of how the experience was for the three of you and if so, why do you think that was the case?

We all had different responses to the stress of this bewildering situation: my mother begins to collapse into laughter, my father becomes sort of deer-in-headlights frozen to the spot, and I grow very irritated, because I don’t feel my father is correcting my mistakes stringently enough. But I also consciously chose three different emotional responses to include in the edit in order to contrast them to one another. All three are different legitimate responses to the stress, and we actually all experienced all of them at different times.

I think most of us learn the pronunciation of our last name from our parents (or father in a “traditional” household where the mother takes the father’s last name), but the three of you seem to pronounce it differently. Is there a “correct” pronunciation of Katchadourian?

Through the piece we discovered that we all pronounce it differently, and I found this quite interesting, along with the very question of “Who’s pronunciation is correct?” My father is Armenian and it’s an Armenian name, but he is not pronouncing it the way you would if you were speaking Armenian—it’s been Americanized. My mother’s pronunciation brings along her Finlandswedish accent, and I suppose mine is even more Americanized. All of us have ended up with some new hybrid way of pronouncing our family name.

Handheld Subway, 1996. Courtesy of the artist and Catharine Clark Gallery.

Have you ever gotten advice, especially early in your career, that you ignored and were glad you did?

When I was considering where to go to graduate school—and graduate school was really an experiment in sorting out whether or not I wanted to be an artist at all—it came down to two schools, one of which was a very well-known school in Southern California which had a reputation for producing very commercially successful artists. The other school I was considering was UC San Diego, which had an eclectic and very transdisciplinary MFA program, quite small. A professor at the famous school told me there really was no question which program I should attend, and that I’d never have a real career if I attended UC San Diego. That sounded like bullshit to me, and I also knew myself well enough to know that studying somewhere which was a bit less in the spotlight and bit further from the fantasy of “the art market that awaited” would allow me more freedom to experiment. I just had a gut feeling UC San Diego would be a much better fit for me, and it was. I got to study with some amazing people there, a few years before they retired (David and Eleanor Antin, Allan Kaprow) and people in other places in the University as well, such as composer and performer George Lewis. I came out of my three years there with an MFA and a much better sense of what I was doing.

Photograph by Jan Windszus for Die Raum.

Do you have a favorite medium (photography, video, sound, sculpture, etc.) or is the medium simply chosen for what makes the most sense for the artistic concept you are conveying? Can you give an example?

The latter. I often say it’s a question of “Pick the right tool for the right job.” But I also struggle a bit with certain media, in the sense that I am really not crazy about having to sit at a computer all day, like when I’m editing a film or a sound piece. I hate that process, physically, although I love it intellectually and creatively. Lately, I have really been enjoying working more with physical materials and I have three consecutive shows this summer in Berlin at a project space called Die Raum which are very physical, built environments. The last of the three shows at Die Raum, which is called “Das Seepferdchen,” opens August 12.

Nina Katchadourian, “GIFT/GIFT” (1998) from Nina Katchadourian on Vimeo.

I admire how you are able to be so prolific and still incredibly meticulous in your work, for example, in your work with maps, your Sorted Books, the Mended Spiderwebs series, and even how perfectly the videos sync up in Under Pressure. How do you manage your time?

I constantly feel like I’m never getting anything done, so it’s nice to read that. Although this might sound odd, there is a certain equilibrium of busy-ness which is good for my process. Not being busy enough or being too busy are both bad for the work. I like having a lot of balls in the air. For me, it’s often very useful to have one project to turn to as a way of taking a break (or avoiding) another, and then the pendulum swings again—it’s what I think of as “productive procrastination.” In the end, everything gets done.

Mended Spiderweb #19 (Laundry Line), from the series Mended Spiderwebs, 1998. (“Uninvited Collaborations with Nature” project). Courtesy of the artist and Catharine Clark Gallery.

Mended Spiderweb #14 (Spoon Patch), from the series Mended Spiderwebs, 1998. (“Uninvited Collaborations with Nature” project). Courtesy of the artist and Catharine Clark Gallery.

Who (or what) has influenced you the most in your work? Have you had or do you currently have a mentor? Do you mentor others?

My strongest influences lie as much with certain family members (my maternal grandparents, for instance) as they do with artists or musicians. I would love to have more mentors, especially women older than me. I do feel like I’ve become a mentor of sorts to many of my former students, or at least that’s what THEY say!

Mended Spiderweb #8 (Fish Patch), from the series Mended Spiderwebs, 1998. (“Uninvited Collaborations with Nature” project). Courtesy of the artist and Catharine Clark Gallery.

What advice do you have for those of us who try to teach/encourage creativity?

I teach a graduate seminar called “Why Do You Want to Make It, and How Can You Make It Better?” and although I can hardly say I hold the answers to that, I do believe that the question and the inquiry that follows is the way to help students better understand and improve their work. Not just students—any artist.

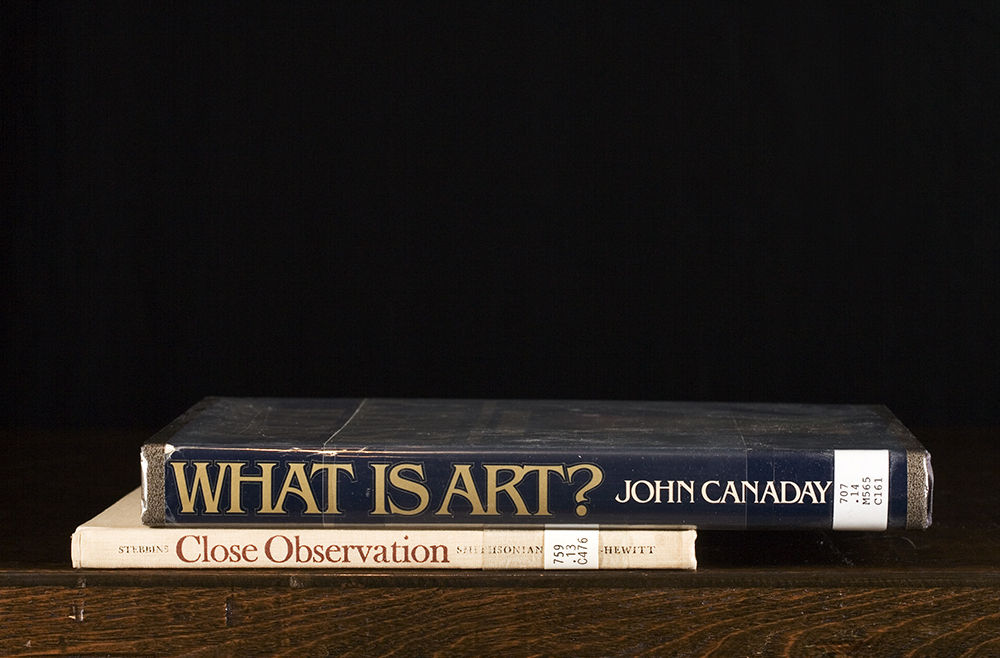

What is Art?, from the series Special Collections Revisited, 1996/2008. (“Sorted Books” project, 1993–ongoing). Courtesy of the artist and Catharine Clark Gallery.

What is the importance of play in your work? In your life?

Here is a quote I’ve been thinking a lot about lately:

There is really no great difference between work and play. Good play is like good work, bad play is like bad work… All good play requires physical and intellectual effort. If you buy the child a mechanical mouse, you may wind it up all day and the child may watch—there is nothing good about this sort of play! The child is passive. If your child is occupied only with such games, he will grow up without initiative, unaccustomed to undertaking new tasks or work, or to overcome difficulties. Play without effort, play without activity, is bad play. In this respect, play is very like work.”

—Anton Makarenko, “Lectures to Parents,” from The Collected Works of Makarenko, Vol. 4, translated by Elizabeth Moos, 1951, as quoted in the Redstone Diary 2018: Play.

Wigeon, 2011. (“Seat Assignment” project, 2010–ongoing). Courtesy of the artist and Catharine Clark Gallery.

What makes you laugh deeply?

As of yesterday, playing a game with my two nephews (ages 3 1/2 and 6 1/2) whereby we scream a message (which we evolved together) at a toy airplane: “Donald Trump! You’re a jerk! You’re a poop and a pee! You only like walls, not people! Get out of here, NOW!” and then throw the plane as hard and as far as we can.

Engine Failure, 2011. (“Seat Assignment” project, 2010–ongoing). Courtesy of the artist and Catharine Clark Gallery.

What defines success for you?

When someone tells me that my works has lingered with them, or changed the way they see something in an enduring and ongoing way. Back to the subject of humor for a moment, one of the most moving things I’ve ever been told was when a woman I knew in high school but hadn’t seen since wrote to me to say that her mother had died the year before of cancer, and it had been a really horrible and really hard experience. But towards the end of her mother’s life, she had shown her mother one of my projects and her mother had laughed, really hard. And that was the last time she really heard her laugh deeply. I think it made me realize I had really underestimated the value of art that provides joy, or the release that laughter provides. One more story like this was a woman who came up to me after a talk and told me that my film “The Recarcassing Ceremony” had been very helpful to her because she had lost her son the year before to brain cancer. I think it’s easy for me to forget that art can actually be “useful” in this way.

Sugar Fox, 2011. (“Seat Assignment” project, 2010–ongoing). Courtesy of the artist and Catharine Clark Gallery.

What is some interesting work that you have seen lately?

I loved the photography retrospective of Peter Hujar’s work that Joel Smith curated at the Morgan Library. It was brilliant work, but also brilliant curation—you could sense what it was like to research the work of this artist, and to come to understand the way he saw. I can’t think of many shows where a viewer was brought in so generously to that process.

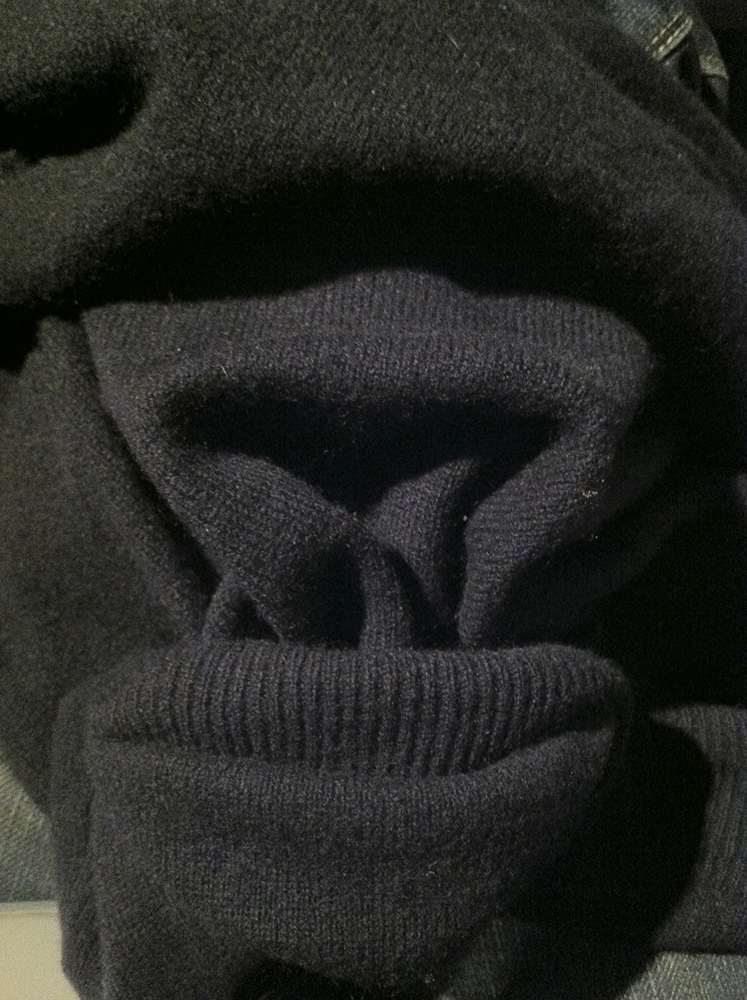

Sweater Gorilla, 2011. (“Seat Assignment” project, 2010–ongoing). Courtesy of the artist and Catharine Clark Gallery.

What is next for you?

About a year ago, my husband and I relocated to Berlin. I live there about half the year, and then I’m in New York the other half of the year to teach at the wonderful NYU Gallatin School of Individualized Study, where I’m on the faculty. This summer, I am working hard on my three shows at Die Raum and trying to learn more German (the exhibition is entirely inspired by the immersive German classes we’ve been taking, and the incredible complexities of German grammar). Come fall, I’ll be back at NYU teaching, and then on a residency at the Rauschenberg Foundation on Captiva Island, FL. Trying to think about what I want to focus on while I’m there—it’s such a luxury to be granted this time, and there are many things I might want to do!

Photograph by Jan Windszus for Die Raum.

Nina Katchadourian

Bio from Roberts, Veronica, et al. Nina Katchadourian: Curiouser. Blanton Museum of Art, 2017:

Nina Katchadourian’s work reveals the creative potential, to use the artist’s words, that “lurks within the mundane,” and underscores the remarkable freedom and productivity that can come from working within limitations. With ingenuity, insight, and humor, her work encourages us to reinvigorate our own sense of curiosity and creativity, and to see our everyday surroundings as a site of discovery and possibility.

Katchadourian’s expansive practice takes place largely outside of her studio. She has made work in libraries, in trees, on airplanes, and in parking lots. She has enlisted help from both far afield and close to home; her collaborators have included sports announcers, zookeepers, museum maintenance staff, ornithologists, musicians, translators at the United Nations, Morse code operators, an accent elimination coach, snakes, spiders, rats, ants, caterpillars, and also her own parents.

Katchadourian lives in New York and Berlin and is represented by Catharine Clark Gallery.

Amanda Dahlgren

Amanda Dahlgren is a San Diego-based photographic artist whose work opens dialogues about the way we live as a society and what we choose to value. Her work has been featured in exhibitions throughout the US and in print and online publications. Amanda is also an educator and mentor whose mission is to challenge and inspire everyone in her care to find powerful and authentic ways to express themselves through the photographic arts. Amanda is currently an Adjunct Assistant Professor at Grossmont College, a Gallery Educator at the Museum of Photographic Arts, Co-Lead Producer for Open Show San Diego, Contributing Writer for Lenscratch, and Chairperson for the West Chapter of the Society for Photographic Education.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Earth Week: Aaron Huey: Wallpaper for the End of the WorldApril 26th, 2024

-

Earth Week: Casey Lance Brown: KudzillaApril 25th, 2024

-

Tara Sellios: Ask Now the BeastsApril 6th, 2024

-

ALEXIS MARTINO: The Collapsing Panorama April 4th, 2024

-

Emilio Rojas: On Gloria Anzaldúa’s Borderlands: The New MestizaMarch 30th, 2024