Laura Larson: Hidden Mother

Laura Larson‘s publication Hidden Mother published by Saint Lucy Books is a an interesting hybrid of photographic history, memoir, essay, and poetry. This book uses the vintage photographic term ‘Hidden Mothers’, of women holding their children for the very tedious acts of portrait photography back in the 19th century all while trying to disguise and hide themselves from the camera.

Laura’s book uses these images of Hidden Mother’s she has collected over time, along side a text that captures her journey of adopting her daughter Gadisse. As the Saint Lucy’s Books website describes so well “Part photography book, part essay, Hidden Mother enlists these strange and powerful images to present a lyrical account of becoming a mother through adoption.”

Laura Larson is a photographer who has exhibited her work both nationally and internationally, including Art in General, Bronx Museum of the Arts, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, SFCamerawork, Susanne Vielmetter/L.A. Projects, and Wexner Center for the Arts. Reviews of her exhibitions have appeared in Artforum, The New York Times, The New Yorker, and Time Out New York, and she has published artist projects in Cabinet, Documents, Open City and The Literary Review. She is the recipient of grants from Art Matters, Inc., New York Foundation of the Arts, and Ohio Arts Council, and of residency fellowships from MacDowell Colony, Virginia Center for the Creative Arts, Santa Fe Art Institute, and Ucross Foundation. Larson’s work is represented by Lennon, Weinberg Gallery in New York City. She earned a BA in English from Oberlin College, a MFA in Visual Art from Mason Gross School of the Arts at Rutgers University, and participated in the Whitney Museum of American Art Independent Study Program. [Bio Text: Laura Larson]

I had the pleasure of talking to Laura about the book and digging a little dipper in to her practice and what this book means to her. If you are interested in getting a copy yourself [which you should!] visit the Saint Lucy Books website here.

First I would love to hear how you started your journey with photography?

I took my first photography class during my sophomore year of college. It was my first ever studio art experience and I borrowed a friend’s camera. I liked it but I was more drawn to filmmaking at the time. I eventually realized that my temperament was better suited to the solitary nature of making photographs.

In your book ‘Hidden Mother’ you tackle the 19th century’s photographic ‘style’ of mothers holding their children still for the long process of taking photos at the time. Can you tell us first what made you interested in this subject matter?

I was introduced to hidden mother photographs by my friend Bernie, an intrepid and sensitive collector of vernacular photography. He thought the mothers would appeal to my sensibilities—their poignancy, their humor. And he was right! I had just begun the legal process of adopting a child from Ethiopia and I recognized in these photographs my own growing feelings of attachment to my daughter.

In the book’s introduction it says “To sit for a portrait was to submit to physical discomfort” from both sides of the image – the photographer and the person being photographed. I found this to be an interesting statement as it really does capture the essence of the time and the state photography was in then. Could you tell us more about this aspect of the book?

I’m interested in the physical aspects of making photographs. Photographers see with their whole bodies, not just their eyes. The nature of nineteenth-century practice, in particular, required a great deal of strength and endurance from both the photographer and the sitter: to hold a pose for seconds, minutes; to operate the heavy and cumbersome equipment. It doesn’t resemble the point and shoot sensibility of contemporary photography. This relates to the exchange that happens between a photographer and their subject—it’s an intimate encounter to make a portrait. Even though I didn’t produce photographs for Hidden Mother, I wrote this book from the perspective of a photographer, thinking about these connections between the photographer and the subject as well as the viewer and the subject. Many of the photographs in the book date to the nineteenth-century so I wanted to evoke the physical aspect of making and posing for a photograph.

How was the process of finding these images? Were there images that you chose not to include in the book, and if yes – why?

I had the good fortune of meeting collectors Lee Marks and John C. DePrez, Jr. who possess an incredible archive of this material. They generously shared their collection for my research. They gave me permission to reproduce selected images as well as to borrow plates and prints for an exhibition of hidden mother photographs that I organized. I also have a very modest collection and some of these images are reproduced in the book too.

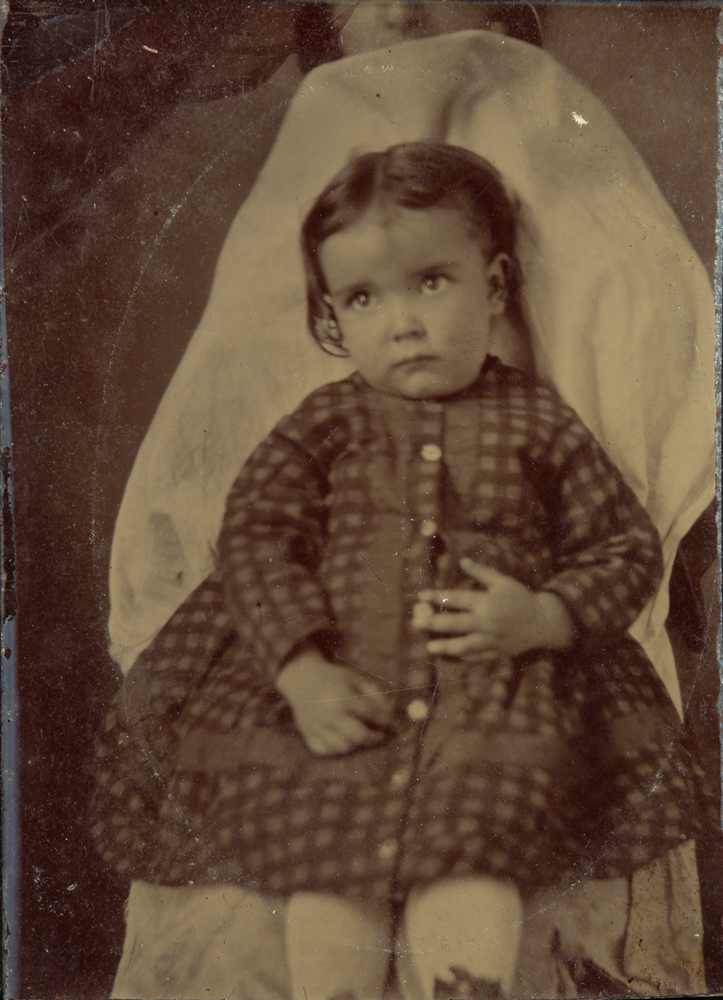

I selected images that resonated with the different facets of the work and my story. For example, I introduce my daughter with a description of the first photograph of her that I receive—an artless, institutional id where she was placed before a plain background. I pair this text with a hidden mother where the child is held against a white piece of fabric, a kind of adjunct backdrop. ID photographs are considered to be a form of objective evidence, highlighting the facts of an individual’s physical appearance. For me, the hidden mother impersonated the trappings of the id photograph with one distinction: the mother can be seen peaking over the top of the fabric. In this pairing, I wanted to point to these conventions of the id photograph and their limitations. Although she was depicted alone, Gadisse’s photograph couldn’t contain her history or her experiences.

Can you tell us more about the two last images in the book – which are very different in time, aesthetics and meaning.

The second to last image in the book is a portrait of myself and Gadisse using the Photobooth application on my laptop. This was the only way I could photograph us together when she was a baby. She hated being photographed, especially by me. I suppose you could call it the one hidden mother photograph that I authored in the book although you can’t see Gadisse’s face either. It’s also the only photograph of us in the book. I’m holding her, facing the camera, and her body’s turning away from me towards it. I selected the image because I thought it was important to include a picture of us but also wanted to be reserved. I didn’t want it to be a big reveal at the end! More like, this is us. The very last image is of an African-American girl standing with a hand very gently touching her leg. It’s one of the very few images I saw where the child was standing alone. So, for me, this child represents that wobbly first moment when a child walks for the first time. I wanted to end the book with the idea about how children, whether adopted or biological, are in some way always leaving us. The last lines of the book read:

Our life together is filled with joy, but the little losses prick and wound every day: when I leave her at school; when she runs towards her friends; when she strays just out of my sight; when I watch her sleep; when I forget about her and when I remember again. I dread the prospect of letting Gadisse go into the world. But, she’s already there.

The concept of these hidden mothers is a subject that has fascinated many artists, what about these women is so captivating to so many, in your opinion?

They’re haunting and evocative images. There’s an implicit violence in how the mothers are removed and I think this speaks to our culture’s deep ambivalence towards mothers and their power. This is why I was initially drawn to this material. As my research deepened, the image spoke to my experience in so many ways: as a photographer, as a future mother, as a feminist deeply engaged with questions about representation of women and the female body.

I think what makes your book so different is the text that accompanies the images. As it says in the Saint Lucy’s website “Hidden Mother tells the story of the adoption of Larson’s daughter from Ethiopia as mapped through nineteenth-century hidden mother photographs.” These mothers are not only a visual reference but in some way a metaphor – is that an accurate read?

Yes, that’s an accurate read. Bear in mind that these are anonymous subjects. I can’t say in any authoritative way who these people are and what their experiences were. I can’t even necessarily say they’re all mothers! I love working with vernacular materials—there’s an openness and freedom in working with images that I didn’t make, a different kind of poetics. I like to think they create a collective portrait of the experience of mothering, which extends beyond my own personal experience of becoming a parent through adoption.

On page 24 you write something that for me made that ‘click’ of really understanding the allegory between you and these mothers. You write “I would wait seven months before bringing Gadisse home and this time would be measured in photographs, a stream of them that formed a virtual umbilical cord between us….Like a hidden mother, I was bound to and separated from my daughter”. Do you mind telling us a little more about this notion and how it connects to these mothers in your eyes?

To parent well, mothers have to cultivate attachment with their children but also make room for them to seek out their independence. That’s what I see in the hidden mother photographs—the mothers are close but also separated from their babies. Again, in this sense, the book uses these photographs primarily as figurative material. There’s a way that children are always moving away from their mothers–these are the everyday losses of parenting. While I was waiting for the legal process of her adoption to be completed, I felt deeply connected to my daughter because of the few photographs I had of her. At the same time, I felt a terrible sense of loss and longing because I was separated from her during this interval.

What was the hardest part of creating this book?

Finding time to write as the single parent of a four-year-old child.

Lastly, as a parent, what do you hope you daughter takes from your experience and from the book? What do you hope she takes from it as a grown up?

Well, she’s ten so I’m not sure how much she can absorb about the book. I know she feels a sense of pride since she knows she’s the subject! She’s attended a few readings and encouraged me not to cry. I hope that as an adult she can understands it as a testimony of my love for her and my desire to bring my life as an artist together with my life as a mother.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

McCall Hollister in Conversation With Douglas BreaultMarch 6th, 2026

-

Olga Fried: Intangible EncountersFebruary 18th, 2026

-

Anne McDonald: Self-PortraitsFebruary 17th, 2026

-

Richard Koenig: Field Notes: View from a Hotel WindowFebruary 13th, 2026

-

Beyond the Photograph: Editioning Photographic WorkJanuary 24th, 2026