Allen Morris: The Same Dirt + Silent Sentinels

This week, we will be exploring projects inspired by place. Today, we’ll be looking at Allen Morris’s series The Same Dirt and Silent Sentinels.

I met Allen Morris at the 2019 Midwest Society of Photographic Education Conference in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. The pre-pandemic introduction allowed me to follow his work, and I was so excited to see him move to my home state of South Dakota. It’s been wonderful to watch how his work has progressed. Allen’s work focuses on the idea of place, so he was among the first people I asked for this feature. He explores place through the landscape photograph, and his work goes deeper into conceptual ideas of space, time, and history. The works are much more abstract but are very true to the regional landscapes.

Allen Morris is a photographic ar1st based in South Dakota. He is an Assistant Professor at Black Hills State University in Spearfish, South Dakota where he teaches classes in the Department of Art and Department of Mass Communication.

His research relies on a variety of light-sensi1ve materials, both digital and analog, coupled with contemporary and historical photographic processes and techniques. Morris’ work examines the relationship between humans and their environments with a par1cular interest in the impact that they have on the crea1on and evolu1on of human iden1ty in social, personal, and political levels.

His work has been exhibited in the United States and internationally. He is an active member of the Postcard Collective and the Society for Photographic Education.

Follow Allen on Instagram at: @allenm82

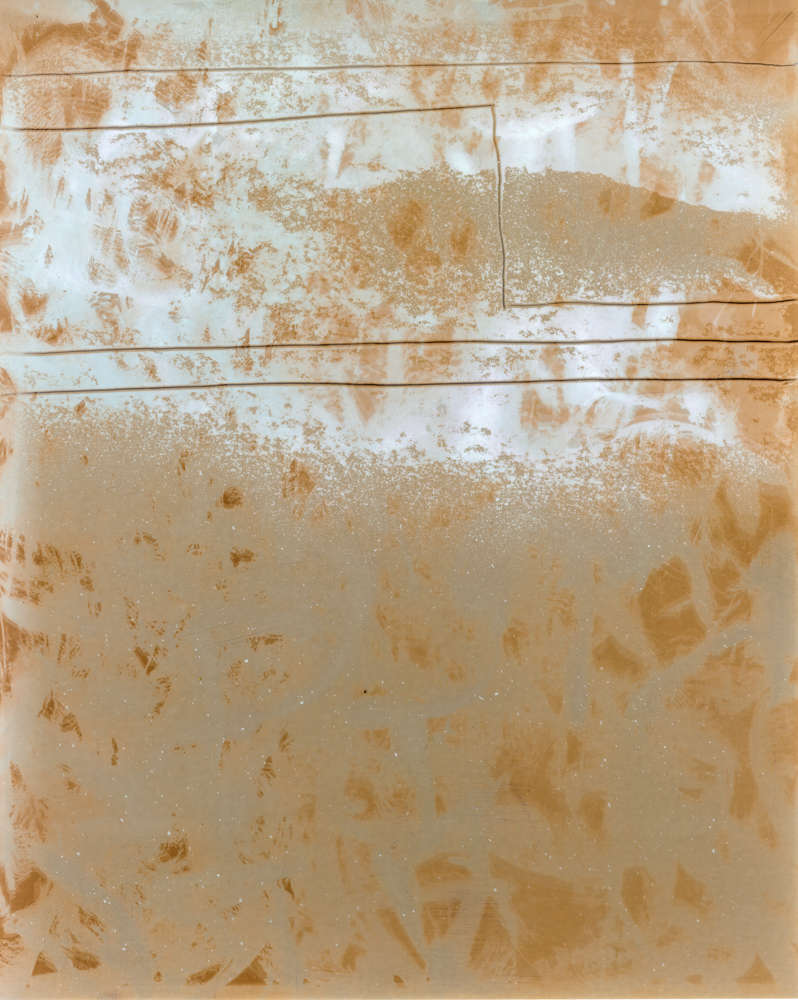

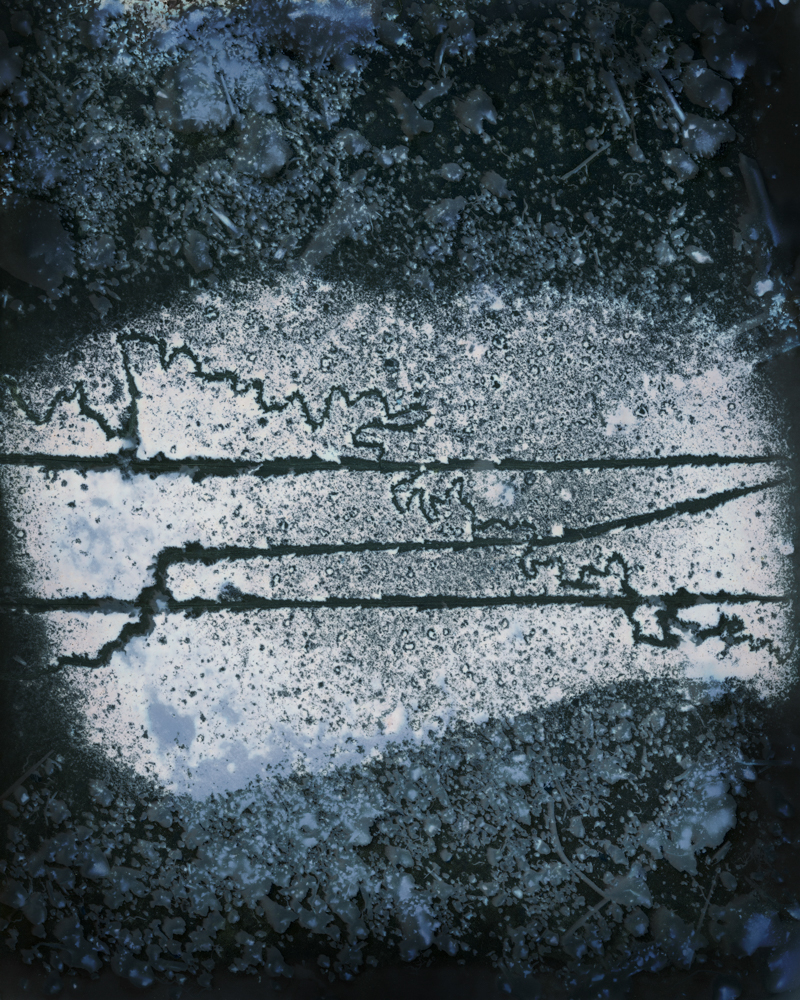

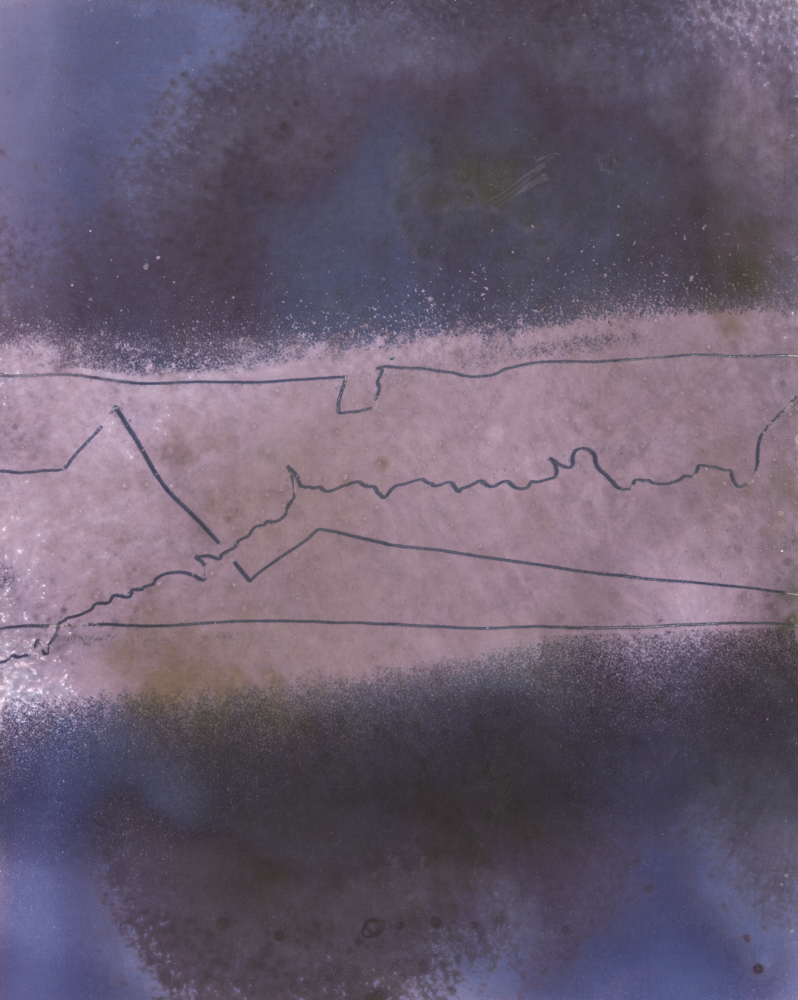

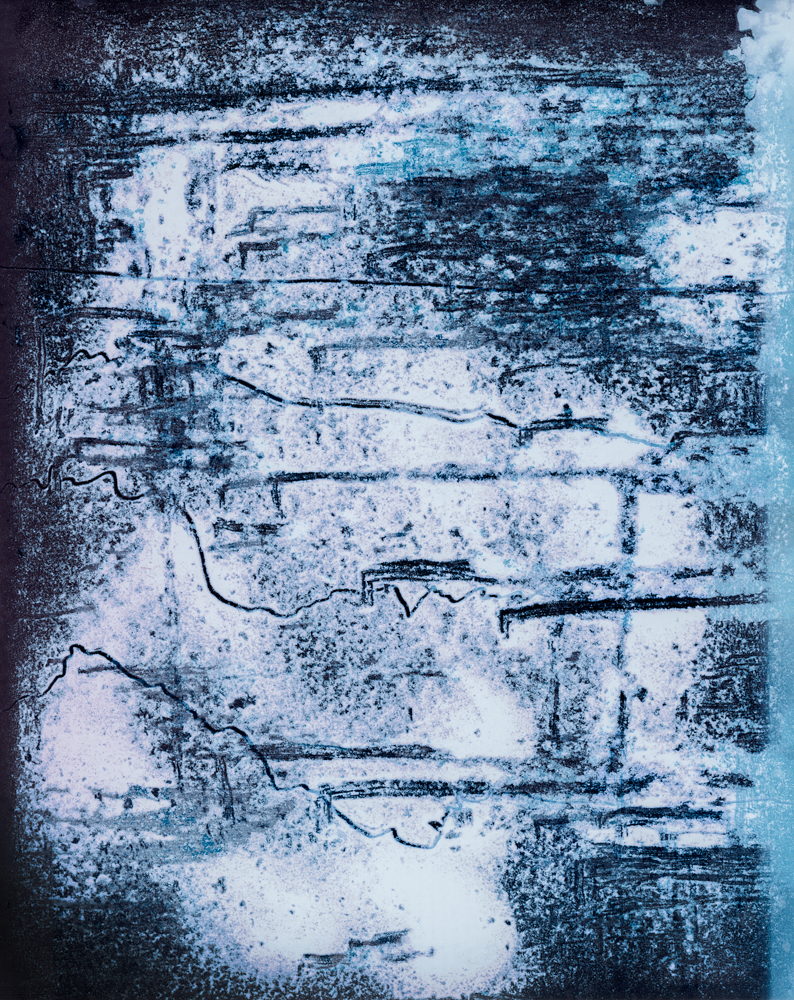

The Same Dirt

A multitude of lines exist in the world that divide us from one another, some are visible, and others are more conceptual. Regardless of their physical or ethereal form, these demarcations also impact the opportunities that are afforded to those that inhabit the space on either side of the line, they determine how the land and resources are managed, but perhaps most notably – these lines help us define who we are, they define our place in the world.

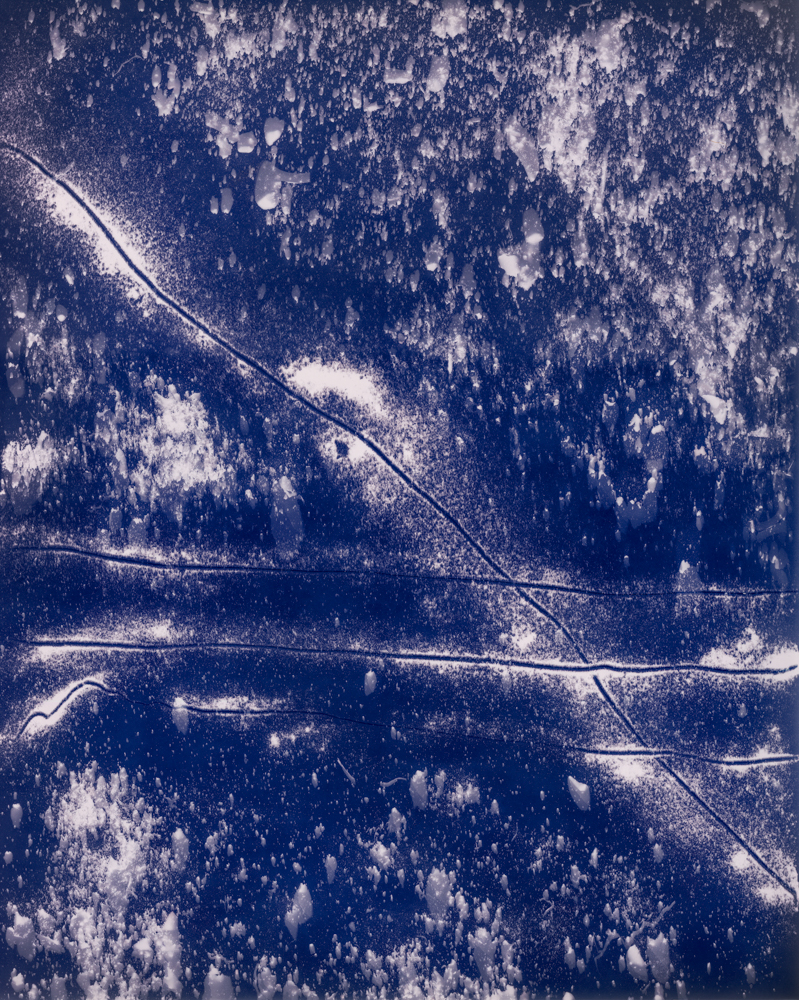

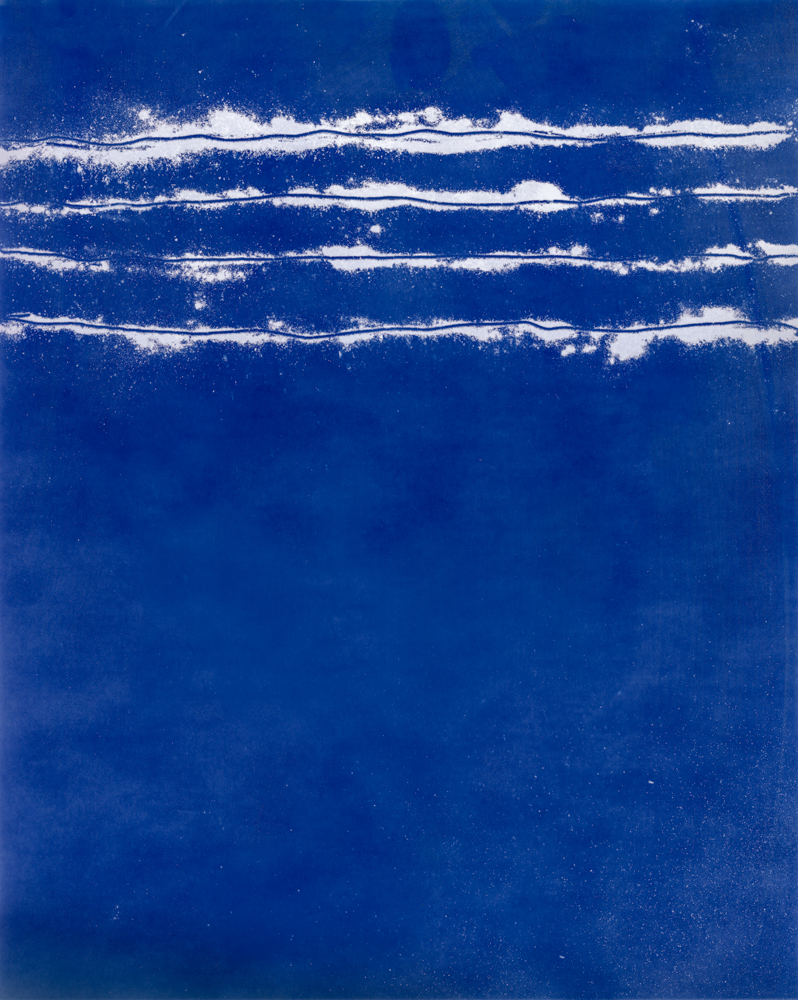

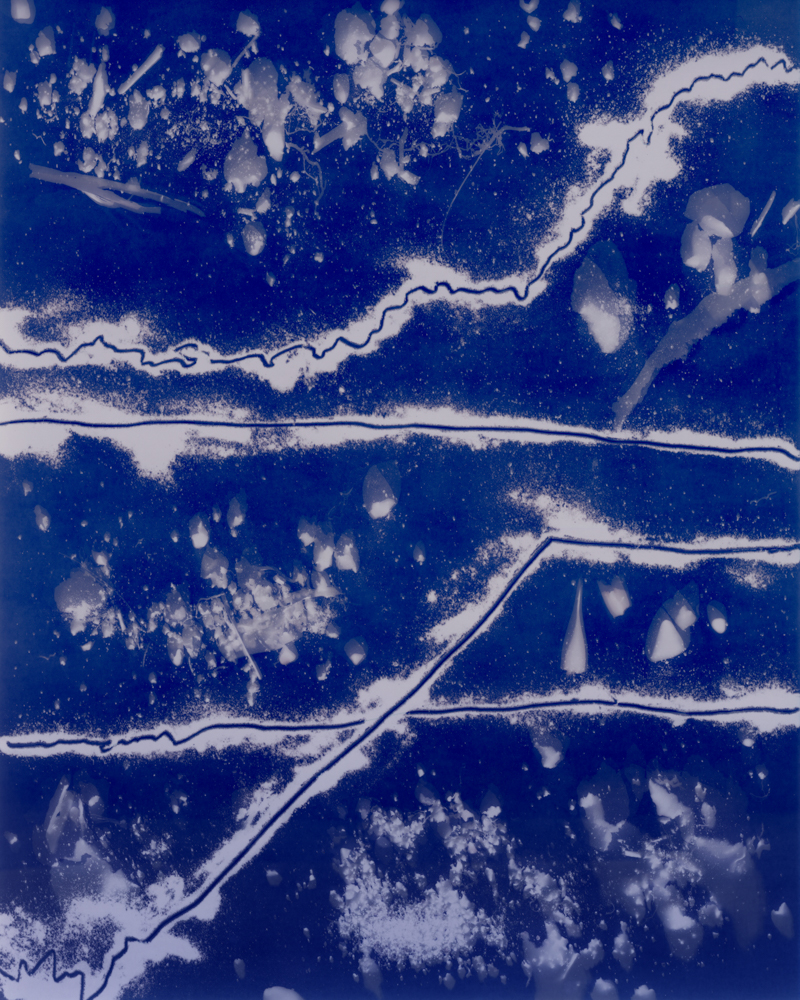

The images that comprise The Same Dirt question these lines, their importance, and explores their perceived permanence. By deconstructing these lines, my work opens the spaces that these lines once enclosed and returns the whole of the land to a singular place. Each image is titled based on the motto of the state that served as its impetus; however, in the same way that the borderlines were decontextualized to create the compositions, the verbiage of these mottos is also reconsidered. This reformulated turn of phrase may provide a clue for viewers, but for most the location will remain obscured.

My work incorporates a layer of comingled soil samples collected from around the country that is laid down on the surface of the paper. The deconstructed border lines are drawn through the dirt, thus allowing for the light of the sun to impact the surface of the light sensitive paper. These ephemeral images are scanned, printed digitally, and archived to allow for presentation and for continued evolution of the original light sensitive object.

Silent Sentinels

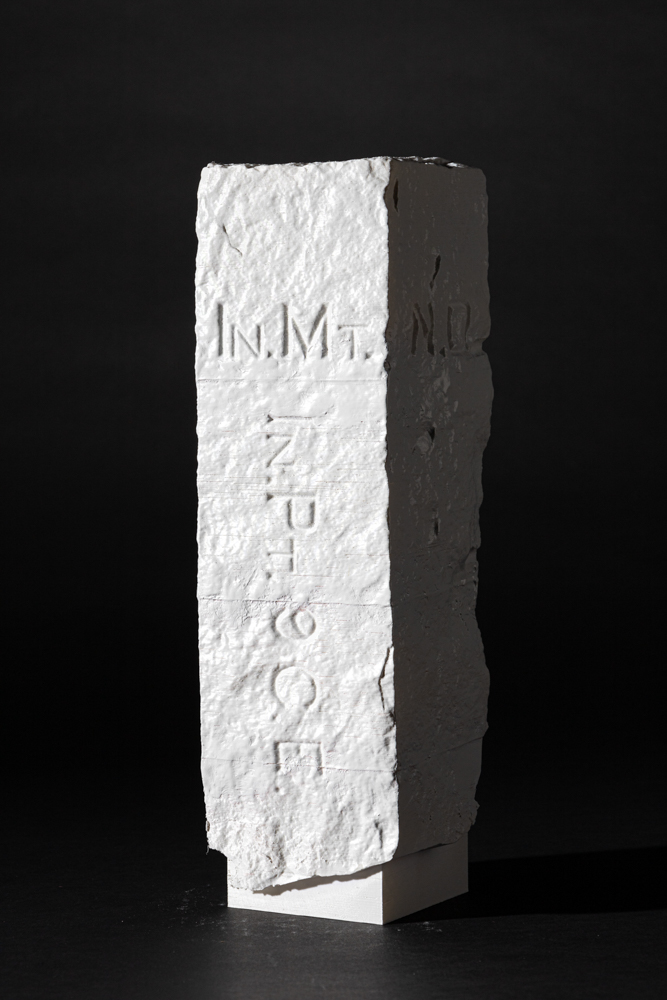

The sculptures and images of “Silent Sentinels” focus on the invisible line that divides North and South Dakota and upon which lies a string of quartzite monuments. These obelisks are engraved with symbols and glyphs seemingly indecipherable to those except the men who placed them in this vast landscape. These markers serve to separate a land that was, not long ago, united under a singular name that is now divided. A landscape bearing the name of the indigenous inhabitants from whom the land was stripped, bifurcated, and sold off parcel by parcel.

This line of stone monuments to politics, separation, and territoriality will be documented and explored in the body of work titled “Silent Sentinels,” a series of photographs, photogrammetric models, and 3-D printed sculptures. Each of the objects makes no attempt to hide the cracks in their facades, lines left behind from the 3D printer, and exposed seams as a reference to the humanmade nature of their existence, not unlike their quartzite originals or the line that they demarcate.

Removed from the context of the landscape that they divide, these individual markers become impotent reminders of the power that these borderlines have socially, politically, and economically not only between the two states named “Dakota,” but all the borderlines within and outside of the United States.

Epiphany Knedler: How did your project come about?

Allen Morris: This project started as the natural extension of my last project The Same Dirt in which I decontextualized the borderlines that delineate each of the 50 United States, as I was wrapping up that project, I was also moving to start a new teaching position at Black Hills State University here in South Dakota. After getting my feet under me, I started to dig into the history of my new home and found a particular interest in the border between the two states named “Dakota”. It didn’t take me long to learn about the unique border markers that divide the two places. I was also very fortunate to have found a book about the border written by a South Dakotan Historian to help shore up my research.

I decided that I should go along the borderline and document the remaining border markers in their positions and just bear witness to the line that divided the Dakota Territory at the very end of the 19th century. With the help of a grant from the South Dakota Arts Council and the Puffin Grant, I was able to do just that. Last summer I spent 4 days driving along the border, east of the Missouri River that basically divides the state of South Dakota in half, and created 3D scans

of each of the remaining monuments that were publicly accessible.

EK: What relationship does place or location play within your practice?

AM: I think that the interest in place, and location, and space, have always been an underlying theme of my work, I grew up in rural eastern Oregon and my family has always been very proud of where they are and where I come from. They are hunters, ranchers, farmers, and just love the land and the place they call home. A bit of that has always been in my soul, but I really didn’t have a great handle on it until my years in Graduate School where I was able to put a name to these interests. Since then, as many of us in academia end up doing, I have moved a few times to find work and hone my teaching skills and my art practice. So, along the way I have been very keen on examining the places that I have called home, even if for a short while, in order to help me orient myself to these new locations – to find my place (psychologically, socially, etc.) in them.

EK: You combine a variety of alternative and contemporary processes in these works – can you

tell us about your artistic practice with these materials?

AM: I think I can best sum this up with an accusation thrown at me during a lecture that I gave at the University of Maine – Farmington, where a wonderful lady in the crowd (she genuinely was amazing – we had dinner after my talk, she was brilliant!) accused me of being a “frustrated painter” since I don’t take “real” photographs. After the shock of that brazen attack (I joke) wore off, I really began to think of how important the materiality of the photographic medium is to me. I think it’s one of the best parts of being a contemporary artist – that we don’t have to corner ourselves into specific, traditional methods or materials, that we can instead jump the borders and boundaries between mediums and really make work that is conceptually focused and nurtures ourselves as Fine Artists, not just “Printmakers” or “Painters” or “Photographers.” Now, working in traditional forms is completely amazing as well, but it’s great to have the world

of options at our fingertips.

So, alternative methods of making work seem to really align with the part of my brain that says “You can’t paint!” or “Do you remember the horrors that went down the last time someone put vine charcoal in your hands?!?!?” and allows me to see and render the world in unique ways that are reminiscent of those other mediums; but, also allow me the control that the camera and photographic approaches can provide. Perhaps I’m a 21st century Pictorialist? Plus – what an amazing time to be an artist. With the technology evolving at a breakneck pace, things like 3D scanning and printing technology, and photogrammetry approaches, and all of these amazing new tools and toys at our disposal – why not expand the meaning of what a photograph is, or what fine art can be?

EK: What’s next for you?

AM: Gosh that’s a good question. I’m not entirely sure! I still have half of the state borderline to go document – which hopefully will happen during the summer of 2023; but after that, I haven’t quite landed on what’s next.

In direct conflict of what I had said in a previous answer, I hope whatever it is, is more traditional in approach than what I have been doing for the past few years. I do miss having a camera in my hands and making work the “good old-fashioned way,” maybe a 4×5 camera will come into play and I’ll go running around the Black Hills like a crazy person, but who knows. I’ve learned to let the work guide what comes next – so as I wrap up my 3D printing and call “Silent Sentinels” a done project, I’m also all ears and listening intently for the whisper of the next project!

Epiphany Knedler is an imagemaker sharing stories of American life. Using Midwestern aesthetics, she creates images and installations exploring histories. She is based in Aberdeen, South Dakota serving as a Lecturer of Art and freelance writer. Her work has been exhibited with Lenscratch, Dek Unu Arts, F-Stop Magazine, and Photolucida Critical Mass. She is the co-founder of MidwestNice Art.

Follow Epiphany Knedler on Instagram: @epiphanysk

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Earth Week: Casey Lance Brown: KudzillaApril 25th, 2024

-

Earth Month: Photographers on Photographers, Dennis DeHart in conversation with Laura PlagemanApril 16th, 2024

-

Luther Price: New Utopia and Light Fracture Presented by VSW PressApril 7th, 2024

-

Artists of Türkiye: Eren SulamaciMarch 27th, 2024

-

European Week: Sayuri IchidaMarch 8th, 2024