One Year Later: Christian K. Lee

© Christian K. Lee, from Armed Doesn’t Mean Dangerous, Aaron Banks, 38, and his son Aaron Banks Jr., 08, embrace at a local park on Saturday, May 22, 2021 in Cedar Park, Tx. “The image of the average gun enthusiast needs an update,” Mr Banks said. He is the President of Keep Firing LLC where he has made his son the CEO. Currently he is one of 24 Pistol Instructors certified by the National African American Gun Association.

Over the next three days, Drew Leventhal, the 2022 Lenscratch Student Prize Winner, interviews the Top 3 Lenscratch Student Prize Winners of 2023. He shares a conversation today with Christian K. Lee.

Christian K. Lee is a much needed truth-teller in a world full of bad information and faulty narratives. He is never afraid to speak from his experience: as a Black man, as a veteran, as a recent MFA grad, as a resident of both Texas and Chicago. But Christian’s work is not only about the self. What I found most inspirational is how much his work is about the people he surrounds himself with, the community he is tied into.

Christian sees the stories or the pieces of the world that the rest of us miss or intentionally ignore. Photography in his eyes is a way of reflecting and understanding the world around us. It is also a connecting force, something that engages the photographer and the viewer and the subject to confront each other, to see each other as human beings with stories and desires.

I first saw Christian’s work a few years ago on Lenscratch. It was during the height of the pandemic and he was photographing kids who had not been able to go to prom. I was taken in our conversation with the way he described the importance of that ritual. This discussion made me wrestle with deep truths about photography. I hope it does the same for you. – Drew Leventhal

Christian K. Lee is an artist living in his hometown of Chicago.

His experience as a documentarian drives his desire to utilize Art as an investigative tool. Christian’s goal is to create imagery that reflects the world in which he currently lives. Lee’s work has been exhibited internationally. It has also been recognized by Arnold Newman Prize, Critical Mass Top 50, and Sony World Photography Awards.

Follow on Instagram: @chrisklee_jpeg

© Christian K. Lee, from Armed Don’t Mean Dangerous, Jamyce Brown, 29, right, embraces her husband Keon Brown, 27, outside of their home on Sunday, April 18, 2021 in Killeen, Tx. “In my hometown introducing a child to a gun may be potentially setting them up for failure,” Chicago native Jamyce said.

Drew Leventhal: Christian, thank you so much for being here and speaking with me! You just graduated from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago (SAIC), this must be an exciting time. It’s the end of school and the beginning of a new chapter of your life and career. How are you feeling? How has the year been since you won the Lenscratch Student Prize?

Christian K. Lee: Drew thanks so much for having me. I’ve learned a lot of new information in the past couple years and I’m excited to use it. It’s a transitional place. In regards to the Lenscratch Prize, it’s been really great. I appreciate everyone who chose me for the award and all the sponsors who sent me gifts. I really benefited from my year long mentorship with Aline. So again I just want to thank everyone who contributed to the Lenscratch Student Prize. They’re invested in photographers and I’m excited and grateful to have been able to benefit from that.

Drew Leventhal: That’s awesome to hear you had such a good experience. Before we dive into the pictures themselves I want to ask about the transition period coming out of school you mentioned. It’s a real thing and it can take time to adjust. I was wondering if you could describe that adjustment. It is different for everybody and it can be scary. What was it like for you?

Christian K. Lee: I think my transition may have looked a little bit different. I was working full time before school and doing my practice on the side. So I feel like I’m just going back to normal in some way. I had sustained a practice before going into grad school from my time in the Army. Again in a lot of ways leaving school is like going back to normal.

Drew Leventhal: That’s an interesting way of putting it. A reverse transition back to normal. We should think about it that way more. Grad school really is a world unto itself. An important one, but not a very realistic one. You come out of it with all this new knowledge but you have to remember how to operate and sustain a practice in the real world.

I didn’t know that you were in the Army. When did you start doing photography, was it before or after you joined the military?

Christian K. Lee: I started doing photography way before I joined the Army. I started photographing about three years before the Mike Brown protests (in 2014). And that was really my introduction to what photographs could do. I joined the Army about 9 years later, and then on to grad school.

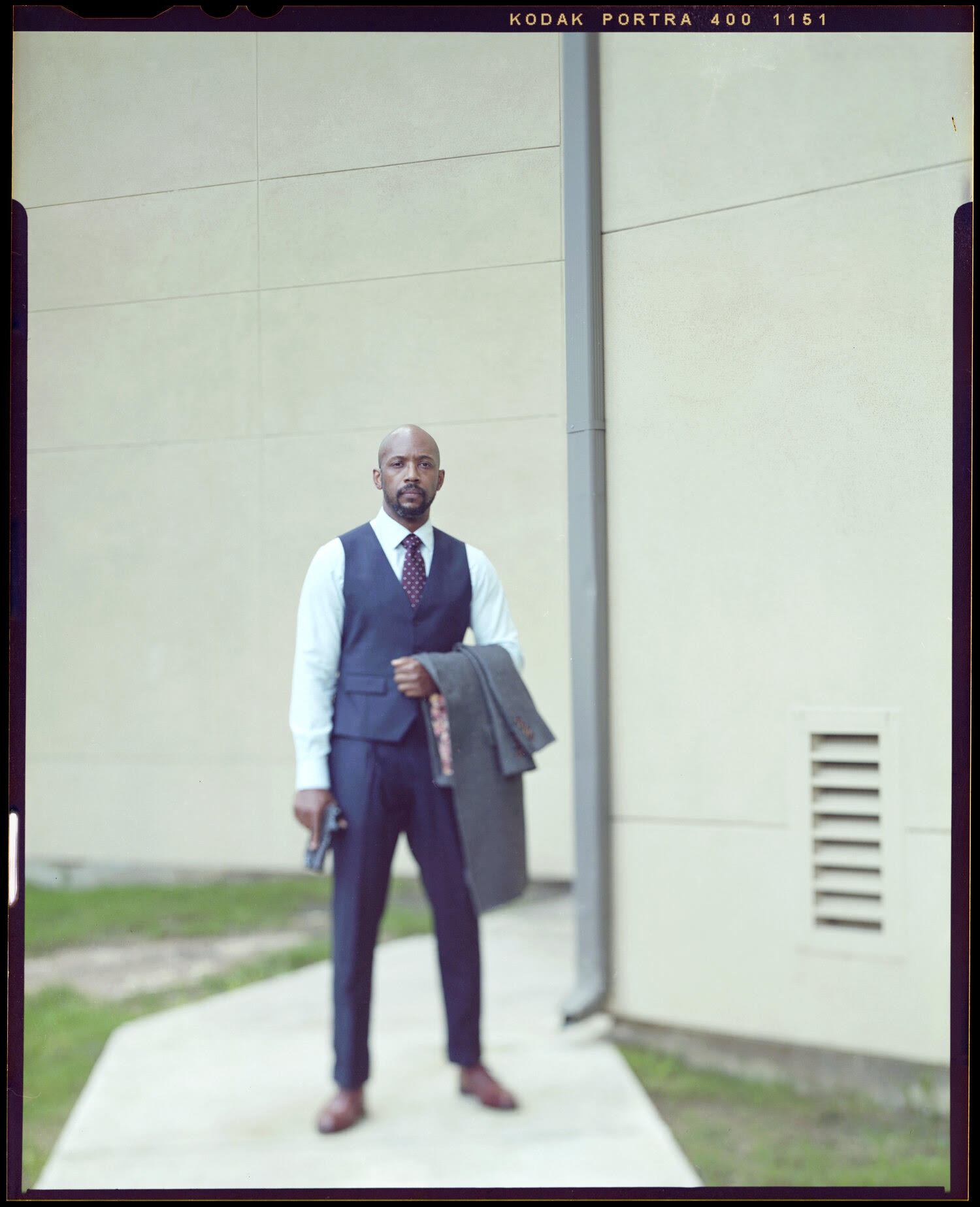

© Christian K. Lee, from Armed Doesn’t Mean Dangerous, Brandon Antone, 37, stands outside of his apartment complex holding his firearm on Wednesday, May 26, 2021. Antone started a Facebook group with nearly 2,000 members in the Austin area with the goal of creating a safe space for African Americans to talk about firearms. “I noticed when I go to the range it wasn’t a lot of us there so I wanted to create a place we could talk about guns,” he said.

Drew Leventhal: I want to jump into the work that you submitted for the Lenscratch Student Prize. I’m gonna start with your overall approach as an artist. You mentioned in your artist bio this kind of blend of art and documentary. Do you see work as being a blend of documentary/journalism and fine art? Or, do you see the artist as being a documentarian in some ways.

Christian K. Lee: Having just left SAIC I’m gonna give you a very different answer than I would have given you two to three years ago. I see my work as an extension of myself. I’m happy you asked this question because I think so many times art isn’t an extension of people’s actual life. I want to see more of that in the art world. We go through different stages of our lives. We encounter grief, we encounter happiness, we encounter love, we encounter pain. But so often you only see one piece of somebody in an artwork. Just one piece of what’s inside.

So when you ask me if my work is documentarian, it’s not in the traditional sense. I will use photography in any way possible to capture things that I experience or things that I feel. If I’m feeling happy, I want to photograph it. If I’m feeling sad, I want to photograph it. If I feel like some injustices are being done in my community, I want to photograph it. So I’m a documentarian in that sense, the sense of capturing the fullness of what is around me and in me.

Drew Leventhal: Very interesting. Journalists or documentary photographers are limited by a code of ethics, right? They’re beholden to some fleetingly objective reality, a concept debatable to its core. I think what you’re getting at is that an art practice is in many ways the product of a complex life well lived. This is work that stems from who you are. And there’s a lot of artwork that’s been done about identity. It can be rather beautiful work. But I think what you’re saying is really important because it’s about the complexity of a lived life. We have multiple identities as artists, as lovers, as parents, as citizens and activists and workers. All these different things are part of us. To ignore those pieces, to not address them in some ways, is to preclude art that cuts to the core of one’s humanity.

Christian K. Lee: This is one of my favorite subjects to talk about. A lot of times artists get wrapped up in the result, the end form, the goal of what is it going to take to end up in a museum? What is it going to take to end up on somebody’s wall? What is it gonna take to be collected? People start censoring themselves before the work even comes out of them, before the work is even a reflection of themselves. We start thinking about what the audience wants to see.

I don’t want my work to be like that. I want my work to really reflect what I’m living right now. In 10 to 15 years when people look back at my work, I think it should really be a reflection of that. There’s this Nina Simone quote that I love, she says, “An artist’s duty is to reflect the times.” I really believe that. I want my work to reflect what I’m seeing, what I’m experiencing.

Drew Leventhal: I like what you said about Nina Simone. The artist’s job is to understand or comprehend or investigate the world. I believe that our job is to be professionally curious. Art is about living and being, experiencing and doing. And I think that’s what we have to be thinking about for art. Do you see your work as tied into activism or community engagement in any way? I’m thinking of the way LaToya Ruby Frazier engages the people that surround her work.

Christian K. Lee: I always say that my work is about that 6-year-old version of me as a child who didn’t have a voice, who didn’t know how to use a camera, who always had something to say. And now I’m an adult, I have a camera, I have an audience. I want to say everything that I couldn’t say as that child. That’s really what my life is about. That young boy who saw how his community was depicted around firearms and noticing that something was interesting. Something just didn’t feel right about it. There was a slice missing. Yes, we have this gun problem that needs to be addressed. There are super bad things that can happen with guns and I don’t condone that. But we have this crisis of poverty and wherever you have poverty, you’ll have crime. People live in these communities, right? They don’t want to leave their community and watch it get gentrified. And they want to protect themselves. But I know that there’s not a national effort to stop poverty.

So in a lot of ways, I feel like people are playing with my community. You’re telling us that you want to stop gun violence by banning guns without addressing the needs of the impoverished? Without addressing poverty people will always figure out a way to do crime to try to get ahead. And what about people that wanna follow the law? They should just lay down and be victims of crime?

Am I trying to promote guns in some type of way? No, I’m not. Again I’m having that conversation with that 8-year-old self seeing that something is not right within this narrative. We need to say, “We’re forgetting something.” This work is holding up a mirror to the world.

Drew Leventhal: That’s a beautiful answer. Guns become the symptom of the real problem, which is massive income and wealth inequality. It’s a product of what happens when the system breaks down and people can’t trust institutions. People need to defend themselves, people need to help each other out through mutual aid. Outside of organized institutions or structures.

Christian K. Lee:I’m happy that you mentioned this because when we talk about organizations, we have to talk about people like the Deacons for Self-Defense. These were military veterans, Black veterans, who would return from service and provide security for people like Martin Luther King Jr. and other Civil Rights activists as they traveled through the South. They would protect the community. There is a tradition of veterans coming back home and educating their community. In many ways I view my practices as a continuation of that practice but with a camera.

Jordan Buie, 18, foreground, wears the dress she planned on going to prom with before it was canceled due to COVID-19 concerns on Monday, May 11, 2020 in Killeen, Tx. “I can’t keep stressing myself about something I cant control,” Buie said. Also pictured (left to right) is her brother Caleb Buie, 13, father Burnice Buie, 39, and mother Wilzata Buie, 38.

Drew Leventhal: I did not know that! An interesting slice of history that ties back to your work. Let’s dive into the pictures. You’ve been working with, Black gun owners in Texas and in Chicago. Can you tell me about how you are meeting people? What kind of dialogue are you having with them before, during, and after the picture making?

Christian K. Lee: I started making these images when I was in the Army, stationed in Texas. But everything about this project was influenced by my experience in Chicago. It was a bit challenging starting in Texas because everything that I had seen on the news about Texas and guns underlying issues of race. It was nerve wracking. However, once I sat down and talked to some people they ended up being super helpful. It really taught me that so much of what we know about people that don’t look like us or talk like us comes from what we see on the news. But I found that when I was able to actually sit down with people it made me a better human. People that I thought were racist, just were not racist. I had to overcome my own biases.

I think that’s the power of the camera, because I wouldn’t have felt comfortable walking into some of these establishments otherwise. Now don’t get me wrong, there are some racist people. I’m not naive to that. I think that’s the power of photography. To sit down and be able to talk to somebody on a human level. I say all that because I found it very challenging to walk into gun ranges where people did not look like me. I couldn’t find a Black gun owner at the start. I had to search for people that looked like me. And the people that helped me initially were people that did not look like me. They were able to tell me about some of their friends or people they knew who were Black gun owners. But now I’ve built up enough credibility where I just have to make some phone calls.

Drew Leventhal: I think you touched on something really amazing and beautiful about photography, which is that it’s this unique connecting force. It brings two people together into an encounter. And they have to acknowledge each other as real people, people with stories, people who are alive. I think it’s a really beautiful thing. And I think you, this is like what your work is doing is getting right into the heart of that.

Can you speak to the use of large format and why you chose to photograph in that format? Can you also speak about your choice to leave the film borders exposed? It’s really beautiful and I want to hear how that came about.

Christian K. Lee: I think I left the borders as an ode to the documentary mindset. I wanted to hold myself to a certain ethical scope. By placing that border down and not removing things or cropping things or replacing things it sets the foundation for how this project will be documented. I’m saying, “Hey, I’m gonna place this border here to let you know that everything that you see, it’s all there. Everything you see is exactly how it was captured.”

I think that the idea of what you see is what you get is important with this topic. Because people frame conversations around political agendas. I want it to be just about the people, not even about my opinion. That’s why I do audio interviews with everybody that I photograph. You know, like I don’t speak a lot about them. I speak about the things that people have taught me. I learned about the Deacons for Self-Defense from the people who sat down with me and educated me. This is not an agenda of my opinions, this is their opinions. That’s what the border did. It allowed me to say, “I’m framing this conversation in this way and I’m not taking anything out.”

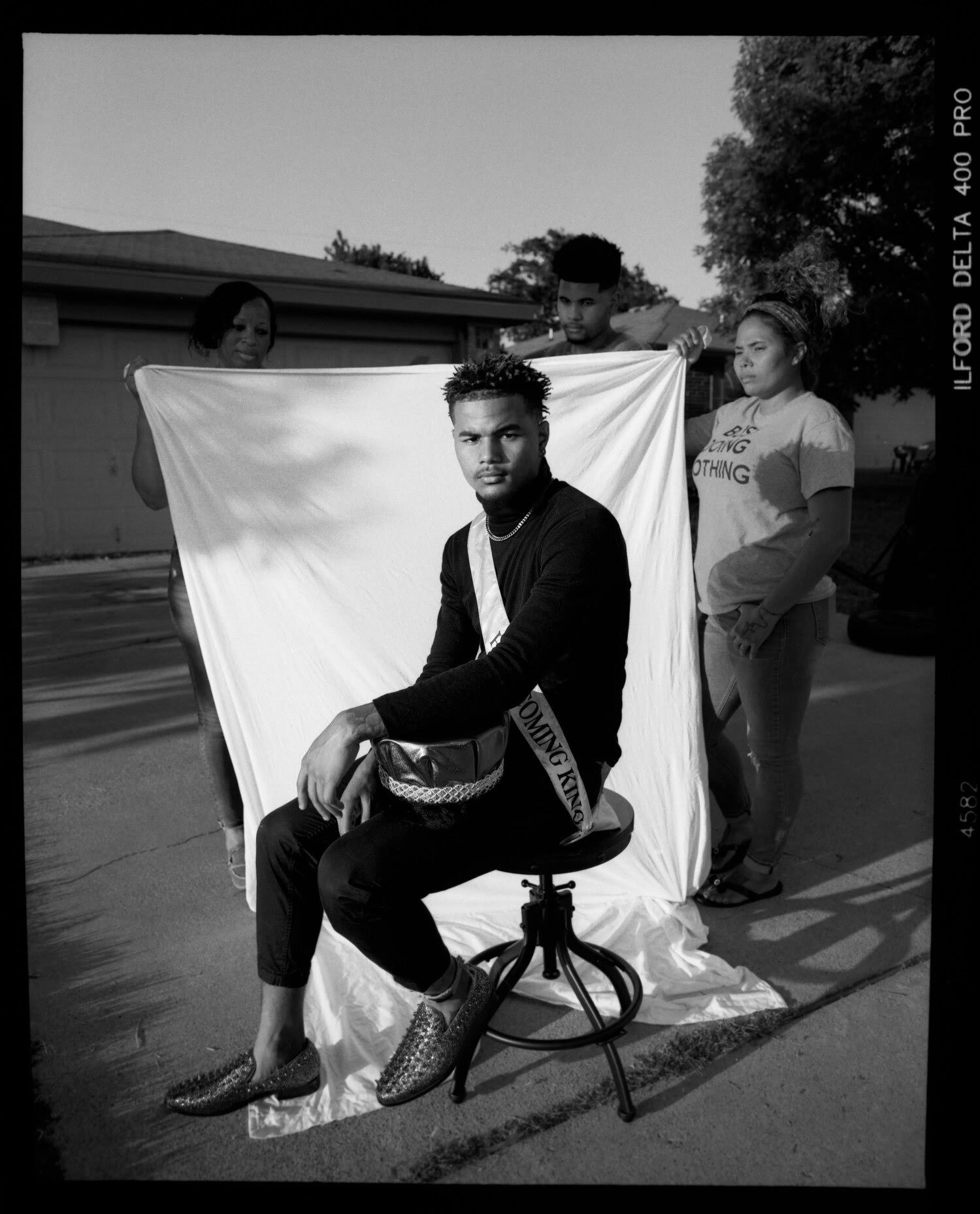

@Christian K. Lee. Demareyo Tittle, 19, foreground, wears part of the outfit he planned on going to prom with along with his homecoming king sash and crown before it was canceled due to COVID-19 concerns on Saturday, May 9, 2020 in Killeen, Tx. “I feel like we wasted our money,” Tittle said. Also pictured (left to right) is his grandmother Erma Allen, 56, brother Omarie Tittle, 16, and mother Juanita Franklin, 36.

Drew Leventhal: What you just said is so true. There’s so much disinformation and decontextualization happening. There’s an honesty to what you are doing, which I really like. Every photograph has a frame. It’s part of the medium. But when you are honest about those frames and you’re honest about those edges, I think that opens up the conversation a lot more.

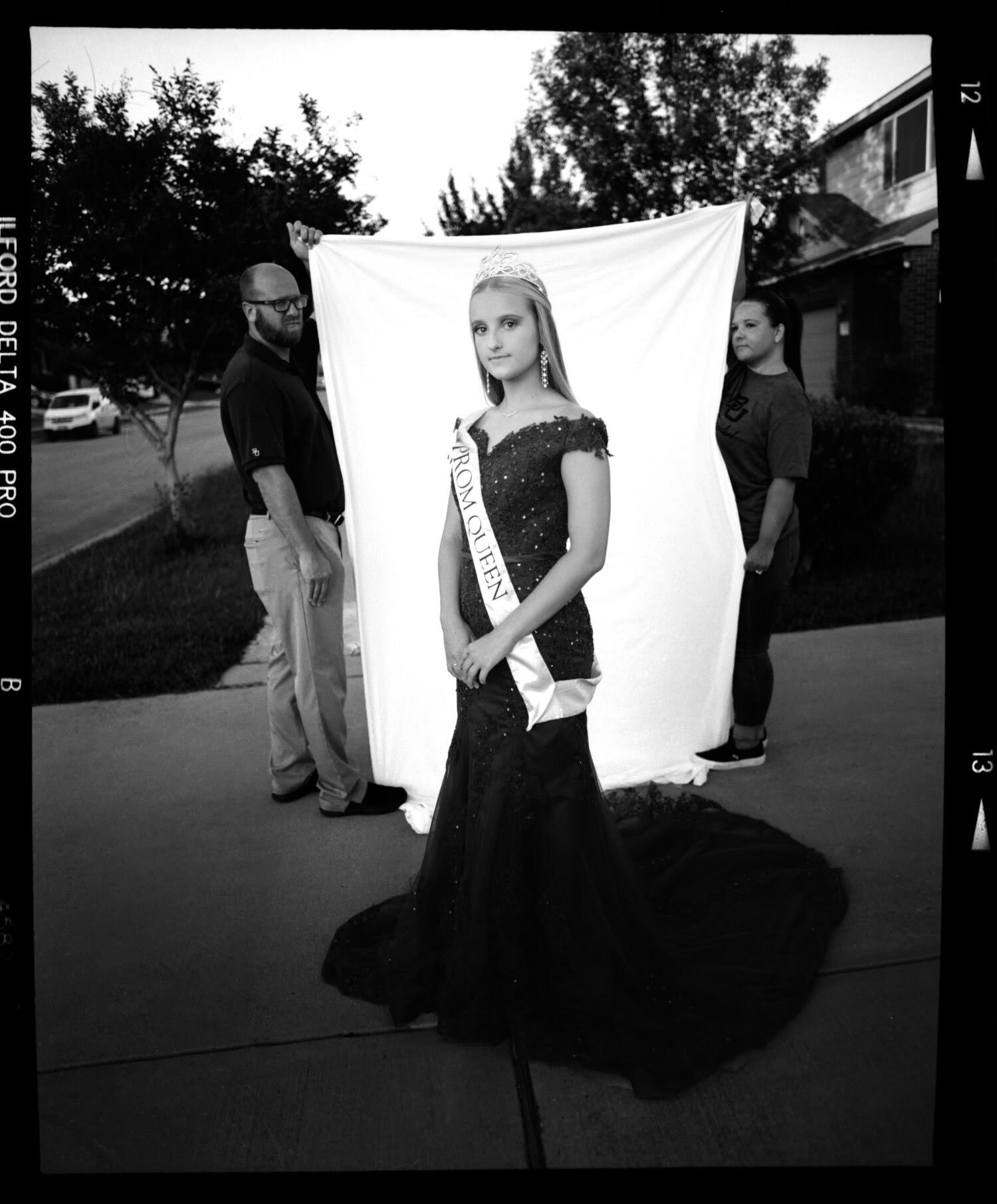

I wanna dive into one of your older projects now. I think this is where I first saw your work, which was Canceled Prom. I was wondering if you could talk a little bit about how that work came about. I know it was during Covid. I know it was during this time where people were canceling events and proms. Why did the prom in particular appeal to you?

Christian K. Lee: Two reasons. I’m from Chicago, and in my community prom is like the biggest thing next to a person’s wedding. We go all out on cars, dresses, suits, I have seen it all. People take horses to the prom sometimes. You know, it’s really a rite of passage. It’s an important ritual. Secondly, I saw that a group of people were gonna miss this rite of passage because of Covid and nobody was talking about it. Again, I’m always searching for this slice that’s missing. I wanted to show how this thing was affecting us nationally, internationally, how it was affecting these local kids. Life kind of just slapped them in the face, passed them by. I wanted to talk about them. The rite of passage that prom represents to the Black community was being lost. It was robbed due to Covid. I think that’s always my approach. What are people scared to talk about? What do people not want to talk about? And I tend to gravitate to those things.

©Christian K. Lee, Faith Dearing, 18, wears her sister’s prom queen sash along with the dress she planned on wearing to prom before it was canceled due to COVID-19 concerns as her mother and father drapes a backdrop behind her on Wednesday, May 6, 2020 in Killeen, Tx. “For two years I waited to run for prom queen to fulfill what my sister did when she was in high school but now I won’t be able to,” Dearing said.

Drew Leventhal: I think we share a lot of similarities in our practices. We both like to photograph things that people are scared to talk about or don’t want to talk about in many ways. I think to myself, “No, we have to confront these subjects head on.”

Coming back to your point on rituals. These rites of passage are so important because they are the way we mark transitionary moments in life. Without going through the ritual, one cannot be considered an adult or an equal member of society. So if somebody doesn’t go through the ritual of prom they would still be a child. When you allow them to be photographed in their prom get ups, doing prom activities it creates a permission structure to say, “I have graduated and I have become a member of the community. I’ve become an adult.” And again, that’s one of the powers of photography.

Christian K. Lee: I think you hit on a lot of the key points. Photography can be a very powerful thing. Thank you so much Drew for having me today. I also want to really thank the Lenscratch jury again. I want to thank Aline for being such a great resource. I think the community that Lenscratch is building, not only for the prize winners, but for everybody who’s sitting at home and either wants to be a photographer or likes the work that’s being created, they can be inspired too. So I just want to say I’m grateful.

Drew Leventhal: Yeah, Lenscratch is very accessible. That’s part of the reason I love it so much. It’s work that people can understand and connect to. But also I think they try to dig a tiny little bit deeper. So I appreciate you taking the time to give thoughtful answers today. Thanks so much Christian!

Drew Leventhal (b. 1995) is an artist and anthropologist concerned with notions of community, historiography, and ritual. Working in an ethnographic style, his images engage with contrasting ideals of imagination, lineage, life, and death. Drew holds a BA in anthropology from Vassar College and an MFA in photography from the Rhode Island School of Design. His work has been featured in numerous publications and has been exhibited across the United States. Drew’s project Mason & Dixon was awarded the 2022 Lenscratch Student Prize and he has been a finalist for the Aperture Portfolio Prize, the PHMuseum Grant, and the Film Photo Award. Drew is currently based in Philadelphia, PA.

Follow on Instagram: @drew_leventhal

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Suzanne Theodora White in Conversation with Frazier KingSeptember 10th, 2025

-

Maarten Schilt, co-founder of Schilt Publishing & Gallery (Amsterdam) in conversation with visual artist DM WitmanSeptember 2nd, 2025

-

BEYOND THE PHOTOGRAPH: Q&A WITH PHOTO EDITOR JESSIE WENDER, THE NEW YORK TIMESAugust 22nd, 2025

-

Beyond the Photograph: Editorial Q&A with Photographer Tamara ReynoldsJuly 30th, 2025