Interview with Owen McCarter and Drew Leventhal: “The Three-Eyed Fish” and Independent Photo Book Publishing

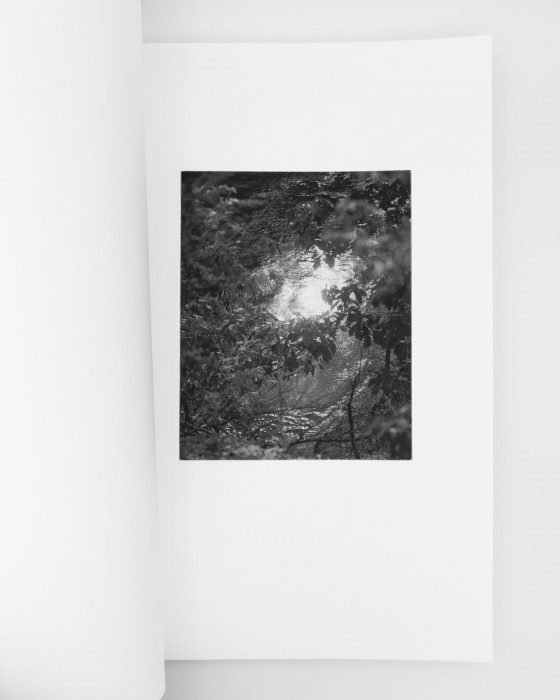

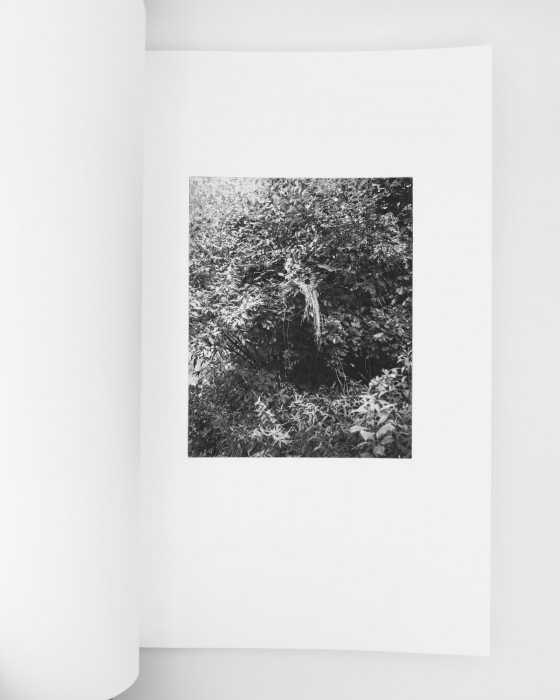

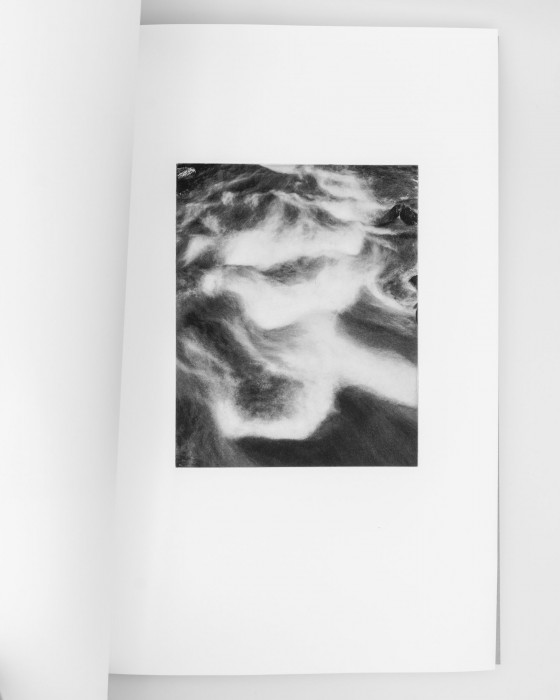

“The Three-Eyed Fish”, by Owen McCarter, is an allegorical journey along the Housatonic River in Western Massachusetts and a search for the pollution caused by a General Electric superfund site at the river’s source. Using both documentary and constructed narrative imagery, the project examines our cognition of place and identity through past, present, and anticipated future experiences. The images question what it means to inherit toxicity and ask how a generation can reconcile with loss while maintaining hope for the future. The book is devoid of historical context, allowing the Housatonic to become universal, a representative of the many rivers struggling with pollution and processes of remediation.

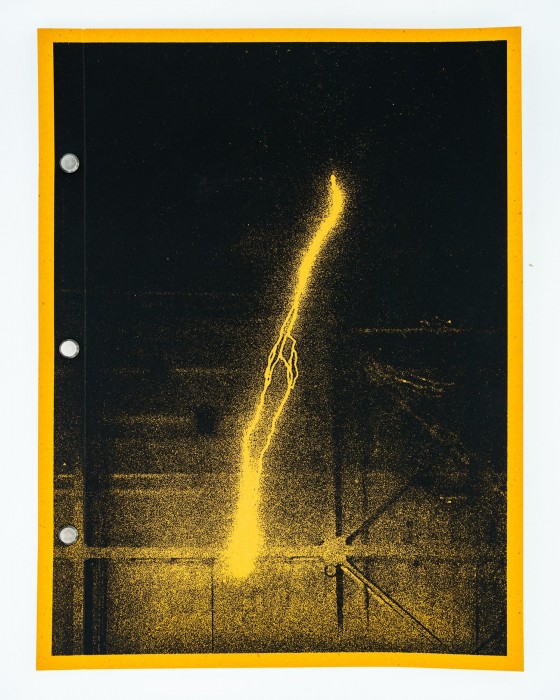

The book itself is handmade from start to finish with the utmost care. The images are handcrafted photogravure prints, a traditional plate-based printmaking technique. The gravure process makes each book a unique object as one sees variations in the ink, press pressure, and marks left by the artist and publisher. In contrast with the beauty of the imagery, the book’s silkscreen cover image and black metal screw-post binding allude to General Electric manuals produced for factories in Pittsfield, MA. Lastly, the size of the book and its inability to lay flat are intended to create intimacy with the reader, requiring touch in order to activate the imagery.

The book was published this past September by Valley Books, an independent publisher of photography books. They were founded in 2023 by Drew Leventhal, who joined me for a conversation about their recent release, alongside the artist, Owen McCarter.

Jumping straight into things, I was curious about the cover design, it feels like such a bold choice for a body for work that’s so quiet and intimate, how did it come about?

Drew Leventhal: The cover is one of those things that was a little bit of a mess… we had to make some very last-minute decisions. *laughs*

Owen had buried these negatives for the project, which was originally the cover. He had been burying 4×5 negatives underneath the soil, letting them decompose over the course of days, weeks, and months, pulling them out, and seeing what happened. They became these really beautiful gradients, some of them looked like stars, and you could still see a little bit of the image in them. The negatives were these amazing representations of the pollution of the Housatonic River. It also mirrored the overall theme of degradation, and I really liked that, so we really wanted to use it as the cover.

We wanted to screen print the cover, which would be a combination of high and low, the book is printed with photo gravure, a high-quality handmade printing style, and we wanted to contrast that with silkscreen, which is usually perceived as a low form of art. It’s a mass form of art, you see it on t-shirts a lot, you see it on posters, so we wanted to combine that sort of high and low.

What happened though, is that the picture we originally chose looked terrible when we tried to screen print it, it looked so atrociously bad, and I spent a couple of nights with the printer just struggling, and borderline crying about how it didn’t work. So, at the last minute, I had to call Owen, and I said, “Owen, we have to change the cover.”

This was happening as we were printing, so he went in and pulled an image from the archive. I think I had seen it before, but we hadn’t done anything with it. It’s an archival image of a lightning bolt, right? From General Electric?

Owen McCarter: Yeah, for a long time, General Electric documented their scientific experiments for use in commercials and advertising. In this one, they were lightning bolting the town of Pittsfield, which is a central place in the project, and it was a test to determine whether the electrical transformers could be resilient to lightning bolts. So, it’s a moment of them constructing a fake town that they destroyed over time through pollution and literally blasting it with lightning.

DL: I think it’s one of those moments where he showed me the photo and I thought, “That’s perfect!”

You know, you have these moments when you’re making books, or you’re working on a personal project yourself, where it’s a happy accident, it was almost like divine fate. Like this original picture didn’t work and then we pulled this image out, and in my opinion, it turned out just as good, or better.

It printed beautifully, and you’re right that it’s a really bold choice, which is eye-grabbing and really good for the book, it’s a nice contrast with the content and sets the scene for what you’re going to see in the book.

Can you talk about that “high and low” in relation to the binding style? It feels like it builds upon that contrast we’re talking about.

DL: Exactly, yeah, the binding style is a screw-post binding, you punch holes through the book and put it together with screws. Again, it’s this sort of combination of mass industrial technology, like these are the same type of screws you’d use in bolting something together in a general electric plant or building an appliance of some kind. It’s that combination of a very fine, tactile book art, and the theme of the project, which is pollution from General Electric.

Also, in terms of the physicality of the book, I feel like the French folds help to offer that counterbalance. I associate them with intimacy, which pairs well with the images and content of the book, alongside balancing out the cover and screw-post binding. What led you to opt for a French fold?

DL: Part of the reason I chose the French folds is actually a very technical choice. I totally agree with you, it conveys this intimacy, it’s beautiful, almost as if there’s hidden stuff inside, but on a very fundamental root level, apart from the beautifulness of the binding, it helps a lot with the printing. We were using photogravure, which creates an indentation in the paper, and I wanted to hide that indentation. I didn’t want the book to be this folio of prints, I wanted it to be a book of printed images, and there’s a fine difference there. So, it helped hide some of the inherent flaws in the printing process. And Owen, maybe you can speak about how it helped us when we were printing

OM: Yeah, the process of doing photogravure comes with tons of mistakes. That’s part of what we liked about it, each page is very individual and holds the marks of making within it. So, you get fingerprints, you get little dots of ink that spill, and the French fold hides a lot of it in the crease of the book. It allows you to print on both sides since the indentations are hidden on the inside. This allowed us to think through sequencing in a different way because we didn’t have to do like, one, one, one, we could play with what we were working with.

That’s a really smart solution to allow for more control over the sequence, I figured there was some technical reason as well.

DL: It’s funny, I’ve seen so many books that use a French fold recently. I was looking at a couple of books in the bookstore last week that used it… maybe it’s the next thing that’s coming in. I think it’s a really awesome binding style and you can do so much with it just on a material basis, like you can hide images within the fold or you can put images across the fold.

Yeah, Elena Helfrecht’s book that came out earlier this year, Plexus, uses a French fold. I don’t know if you’ve seen it, but there’s a wonderful short story at the end, but it’s on the inside of the fold, so you have to cut it open. It’s really cool.

DL: I’ve seen that only online, but I’m excited about it. It’s such a beautiful way of putting a book together.

How has working on this project together been and what has your dynamic been like?

OM: For me, it was amazing. I loved working with Drew. Going to school together, we had the opportunity to be peers and in classes together. We both took bookmaking… we experimented with photogravure in our professor’s basement… we were working together a lot.

Also, Drew was very familiar with my work, we already had a level of dialogue and had been reaching out to each other to talk about work. I think you always need tons of perspectives on your work, it‘s always a product that is created by many. The process was really fun and came naturally as our relationship grew over the years.

DL: Yeah, I agree. This book was really fun to make. It felt like a very smooth, seamless process throughout. There were very few points of tension or hiccups, it was actually from the beginning to the end, pretty consistently smooth, which is great.

I had seen Owen’s work, like he said, in class, but we had been looking at the work together in and out of class for a couple of years. He had shown me this little maquette, like a book of just taped-in prints, which I loved, a lot of which actually ended up in the final project.

I just loved that book and we were talking about wanting to make something eventually… and eventually, it just made sense. It was the right time to do it and it was really fun. I think Owen and I also have a very similar aesthetic, we take pictures about different things, but sometimes there’s overlap in how they look. We have similar sensibilities as photographers, which helps a lot since I think I understood what he was trying to do with the pictures.

The sequencing was pretty easy, we were batting it back and forth for a while just online. Then we sat down and met. And once we did that, it was like a long weekend of sequencing and we got it pretty quickly. I don’t remember it being too difficult if I’m being honest with you, like maybe we made a change or two afterward? It was just one of those books!

Sometimes book projects take a really long time, and I would say, from the first time that Owen showed me this maquette at RISD, to printing it, was maybe two… two and a half years? Something like that.

But the process of like, “Okay, let’s do a book,” to printing it, was maybe a year, which is really fast for some of these projects.

I’m curious, Drew, correct me if I’m wrong, but everything you’ve published so far has been with RISD alums, right? Can you talk about how you’re using the press for community-building and what your ideology for choosing artists is like?

DL: I think it’s half a coincidence that it’s been all RISD people. The first one was mine, so obviously that’s one. Then Alana and Owen are also RISD alums. When I started this publishing company, one of my biggest fears was, where do you find good projects to publish?

I had less fear knowing that I had this amazing community of artists that I went to school with, I could start there and just be like, I love this project, I love that project, then go from there. So, in some ways, it’s almost a coincidence that it’s been RISD so far. I’ve talked to RISD about doing more, like potentially making it more involved with the department in some ways. But in the future, it’s not exclusive to RISD we’re going to be working with other people as well.

I have some books in the works that are distinctly outside of the academia approach, which is cool. Part of the reason I started Valley was to make the type of books I wanted to see, or that I didn’t see quite as much in the photo book world. Especially books that are more handmade, and I think Owen’s book is a good first step in that direction. We’re doing a lot more handmade stuff. I think every book that I make now is going to have at least some handmade element, where I’m doing it myself or the artist is doing it with me.

I enjoy that as a community-building process. We can bring people in to learn new skills, to make new friends, and to make cool stuff together. I think that’s a really good foundation for community. I think a book publishing company as a community-building organization is really powerful because it can bring ideas together and bring people together in really amazing ways.

That’s great, thank you. I think we both have similar outlooks on our presses.

DL: Absolutely. It’s got to be a friend.

You know, part of it is like, you’re publishing people that you know, you’re publishing your friends, like, I mean, that’s not a secret in the photo book world. But I think it’s one of those things… it’s almost a dirty thing. It’s like, “Oh, you’re just publishing your friends?”

Yeah, those are people that I know, people that I trust, people that I want to work with, like Owen, right? I knew that it would be a great book, not because the work is great, but because I knew Owen was great too.

In terms of making the book, Owen, how has it shifted and transformed your relationship with the work?

OM: I think I’ve gotten used to presenting this body of work in lots of different ways. One is more scientific, talking about the ecology of the river and how that’s shifted over time, alongside processes of remediation.

The other is more of a poetic response to how it feels to grow up in a site of toxicity and to inherit that from the environment. This process of making the book allowed me to really dive into the more poetic response and explore what it meant to create a body of images that could talk about an emotional effect, rather than a scientific one.

I felt like there’s this underlying, deeply felt sense of love and reverence for everything you’re photographing. I can just feel how much you care about the subject matter. In the sequence, there’s a beautiful flow of gestures and form between the people, animals, and the land, they feel so intertwined, as if they’re one. Can you talk about how you two went about sequencing the book?

OM: Yeah, I mean, as I said before, we were tossing it back and forth for a little while. There were lots of different elements that we were thinking about and the final product steers away from any of the more industrial photographs. Like there’s not a lot of houses. There’s not a lot of people interacting with each other. It’s more singular.

Mainly objects or elements of the forest and the river… and I think we liked that romanticism that was built, you know, talking about a place that’s considered a toxic waste site in the process of ongoing remediation. Having a romantic look at it makes you renegotiate how humans can interact with that space, and how we can move past considering something as broken, and live in something that’s in the process of healing.

DL: I’ll also just jump in and say, man, we could, and people have, start a whole business about book sequencing that people would absolutely eat up. I know you know this, Jake, it’s like, it’s one of those things that is so tricky to talk about.

We printed out crappy laser jet copies of the images, and we were looking at them on the coffee table, on the dining room table. You look at them, and it either works or it doesn’t work, and there is a way we can talk about how those things interact. There’s mirroring of gesture, there’s mirroring of visual themes and motifs, but like, man, it’s hard sometimes to put language to this stuff.

When I’m looking at pictures and trying to build a sequence, I start snapping my fingers, like creating a little rhythm. It’s almost like music. Like you’re doing a little dance, this picture to this picture to this picture. Then you get to one and it’s not working. It’s like, “Ah, darn, that’s not the one.”

Then you gotta pull it out and you gotta put something else in, you try to get in this one, maybe it works, so you keep going. It’s one of those things that I think you just have to do with practice. For anybody interested in book sequencing, I think it’s about learning visual motifs. That’s what Stephen B. Smith’s bookmaking class at RISD, taught us. Photo books are about conveying ideas and themes, building worlds, and telling stories.

So, you have to have things for people can grab onto, right? It can’t be pure chaos. You have to have structure to it. It can be a loose structure, but you have to have some kind of structure. And so, figuring out what that is and then building the pictures around it is a really helpful way to start. Then, when you get into like the one… two… three… I think of it as music. I think of it as dancing in some ways.

I don’t know how you think about it, Jake. Maybe this is a good place where I can redirect the question at you, but to me, it’s music and dancing. I know for other people, it’s like literature or poetry, so how do you think about it?

That’s actually really funny. Instead of snapping, I do head nods. Sequencing is identical to music for me. I create all my work, books, photographs, everything, based on music.

Making a book is just making an album, so I’m totally there with you. Many of my friends and collaborators also talk about music being intertwined with their photographic practice, so I think it might be common.

DL: Yeah, it’s one of those things that I started picking up on myself doing it. Hearing that you do it too, makes me feel a lot better. *laughs*

But you say it’s it’s common? I’ve never heard anybody talk about that. No one I know has ever said like, “Yeah, I’m bopping away while sequencing things.”

Maybe not in that regard, but I think most of my friends here in Maine are heavily influenced by music. It’s been the most common thread I’ve found lately, maybe it also has something to do with the type of work we’re making? Dylan Hausthor and I talk about music and its influence on us a lot.

DL: Owen, were we listening to music when we were doing this? Or what were you doing? What we were listening to? It was various things, right?

OM: Yeah… I don’t remember exactly what it was though.

DL: Were you doing the same thing though? Like were you bopping along with me or were you in your own space and rhythm?

OM: I always sequence when listening to music, but I’m usually pretty still… I think the process is also so physical, like when we were passing documents back and forth online, it would take so long to look through it, process it, and be able to rethink it and reorganize it. Then, when we were actually together, in the same space with printed images, we were able to just dive in, work for hours, and get through it all quickly.

DL: Yeah, fast decision-making, exactly.

I think, in terms of music, it might just come from it being this medium that you can passively engage with. It doesn’t take up your entire focus, it can be in the background, and you can subconsciously be interpreting its narrative structure. Your brain can be like, “Oh, this is what I’m trying to build in the sequence,” and almost create a reflection.

It’s not like a movie, where you’re actively engaged, and you can’t sequence at the same time. The same goes for reading, or any other medium with a narrative flow. Music’s unique though since you can engage with it more passively. Subconsciously it creates this flow that, when at least I’m working, I try to replicate.

DL: It’s totally true. It’s definitely a flow state. I was just sequencing my own book on the floor a couple of days ago and I was jamming out to music, you know, a lot of guitar riffs and stuff like that. It was funny, I was in a flow state where I was just… my head was in the guitar riffs, but my eyes were like, okay, this picture here, this picture here, this picture here, and it worked perfectly.

Maybe it’s almost like a lizard brain type of thing.

As you said earlier, you two have a similar visual language and vocabulary in your work. So, in terms of influences, do you have a shared overlap there?

OM: Yeah, I mean, part of the reason why I decided to work with Drew is because when we’d hang out together, we’d just sit, talk, and look at books. There were so many shared artists who we admired and ideas about what bookmaking was.

I felt very in tune with Drew.

DL: I agree. I think part of the reason why, as Owen said, it’s been really fun working on this project is that, apart from the book, we’re friends. When we were done working on sequencing for the day, or when printing was done for the day, we could sit, have a beer, and just talk about photography in a really fun way. You know, I think that’s the mark of a good working relationship, and also a good friendship too.

I’m just looking over at my library and trying to pick out who some of our influences were. I would say Susan Lipper comes to mind. I’d say Gregory Halpern comes to mind a little bit, Dylan as well, Dylan Hausthor, and Pia Guilmoth.

What were the books that we were looking at, Owen?

OM: We looked at Parliament of Owls.

DL: Parliament of Owls, Jack Latham. Yeah, that was a great book. I’m thinking of Nancy Rexroth a little bit too. Maybe Alex Soth’s Songbook.

What was the music you were sequencing to?

DL: Ooh, I was sequencing to Mdou Moctar and Khruangbin! I don’t know about you Owen, what did you sequence to usually?

OM: I don’t remember what I was listening to when we did the book.

DL: I think it was like indie rock of some kind. It was something pretty soft.

I don’t want to keep you guys for too much longer, but how does the body of work feel now that it’s a book? Does it feel done, or just like a stamp on where you’re at right now?

OM: It feels very done to me. Finishing it was a big breath of fresh air. I was like, “Okay, I can, stop doing this for a little bit, and then recheck in with it later if I want to.”

I’ve always loved photo books, as most of us do, and I was thinking of that as the final stamp on this project. I thought, if I could make it into a book, that would be incredible and allow me to step away from it.

Do either of you have next-step goals moving forward for your personal practices, bookmaking, or just in general?

DL: For Valley, we have a couple of books in the works. We’re probably aiming to do one to two a year maximum, just because it’s a lot of labor. The handmade nature of them is very labor-intensive… and by we, I mean literally me. *laughs*

I’m thinking about maybe doing a magazine, like a one-shot photography magazine of some kind with some good criticism and good reviews. Basically good thinking, like good analytical thinking about photography.

Part of having a book company is having a wide range of price points too. So, we have Owen’s book, which is on the more expensive end, we have my book on newsprint, which is on the cheaper end, and maybe this magazine could take the spot below my book, being really cheap, easily accessible, and distributable.

That’s what we have for Valley, and then I just started working on my own book which has been four years in the making, and probably another year or two of bookmaking. So who knows when that’ll conclude, but I have a lot of things happening!

What about you, Owen?

OM: I’m onto the next project and seeing where that goes, still in the early stages of figuring it out and making.

Opening the floor up for you two, is there anything else you want to share that we haven’t touched on?

DL: Oh, yeah! I want to talk about Prints on Paper for a second.

We had done photogravure at RISD, and we had begun the process of setting it up in the department, but we hadn’t perfected it or gotten too much experience with it. So, when I pitched doing a photogravure book to Owen, I think he said, “That’s a great idea!”

Then, in my head, I was like, “Great, I have no idea how to do this,” it was kind of a daunting task. *laughs*

But, you know, these guys, Walker and Nathaniel, at Prints on Paper Studio in Vermont, they had just opened. I had actually reached out to them before they even opened, and said, “Hey, guys, I want to do this book. It’s a crazy idea, I know.” Then they emailed me back and they said they were really interested.

I think they opened on August 1st, and we were their first project, it was really fun. We had five of us in the studio and they taught us all the details about photogravure printing and production. We had an assembly line of printing going and we cranked out a lot of books in those four days.

I just wanted to give a shout-out to those guys because they taught us everything that we know about photogravure and also made it really, really fun. I want to support those guys as much as possible, so if anybody needs gravure printing done, they are the experts.

That was the most fun four days of bookmaking I’ve ever had.

“The Three Eyed-Fish” can be purchased here:

Owen McCarter (b.1998) is an American artist living and working in the Northeast. He was the recipient of The Norman and Rose Avnet Fellowship Award and the T.C. Colley Award for Excellence in Photography. His practice engages with colonial history, identity, and landscape.

Follow Owen McCarter:

Drew Leventhal (he/him) is a photographer working with themes of colonial history, family, and the way memory shapes identity. He attended the International Center of Photography and completed his MFA in photography at the Rhode Island School of Design.

Valley Books is an independent publisher of photography books. We focus on small run, handcrafted books that elevate the images they contain. By blending the photographic monograph with the traditional artist’s book, we want to create unique objects that will stand the test of time.

Valley Books was founded in 2023 by Drew. It began as a way to combine his passion for bookbinding with a desire to publish the books he wished existed.

Follow Drew Leventhal/Valley Books:

Jake Benzinger (he/him) is a photographer, book artist, and writer based in Rockland, Maine; he received his BFA in photography from Lesley University, College of Art and Design in Cambridge, MA. His work explores self-created mythos, and through the dislocation of space, he weaves together imagery to construct a world that exists in the liminal—navigating the space between fiction and reality and investigating themes of identity, mysticism, animism, and death.

His work has recently been featured by Float Magazine, Transference Magazine, and Fraction Magazine, and has been exhibited both nationally and internationally. Jake’s body of work, Like Dust Settling in a Dim-Lit Room (Or Starless Forest), was self-published, shortlisted for the 2023 Lucie Photo Book Prize, and sold out of its first edition of hardcover books. A second edition was released in late 2023, coinciding with a solo show at the Griffin Museum of Photography.

Jake is currently the assistant gallery manager, associate curator of photography, and curator of books at Blue Raven Gallery, a content editor for Lenscratch, and the founder/director of wych elm press.

Follow Jake Benzinger:

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Carolina Baldomá: An Elemental PracticeJanuary 5th, 2026

-

Time Travelers: Photographs from the Gayle Greenhill Collection at MOMADecember 28th, 2025

-

Suzette Dushi: Presences UnseenDecember 27th, 2025

-

Ragne Kristine Sigmond: Portraits of Painterly LightDecember 2nd, 2025