Interview with Dylan Hausthor: What the Rain Might Bring

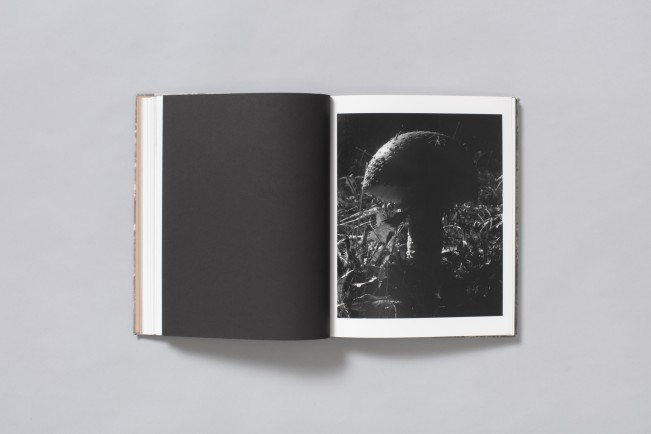

“I was recently visiting my hometown and stopped to fill up my car with gas. I noticed a woman sitting outside the gas station drinking coffee and recognized her as my old ballet teacher. I sat down next to her and we caught up. She had been going blind for a decade since I last saw her. She had fallen out of love, started growing a garden, and found god. She had a small collection of freshly picked mushrooms next to her and handed me one, saying “Mushrooms have no gender, did you know that?”

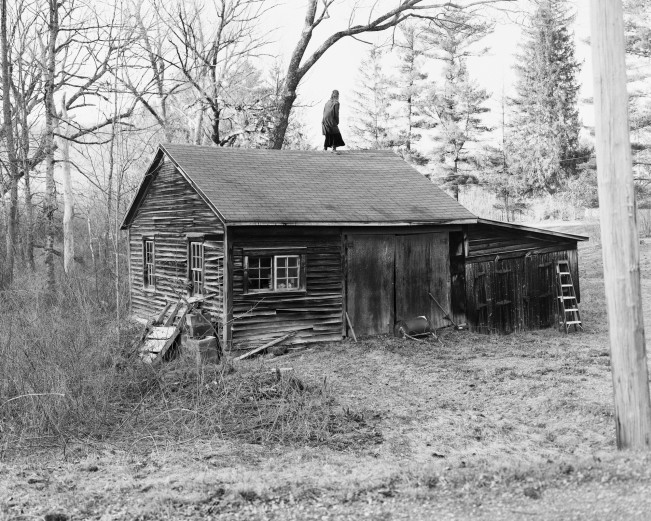

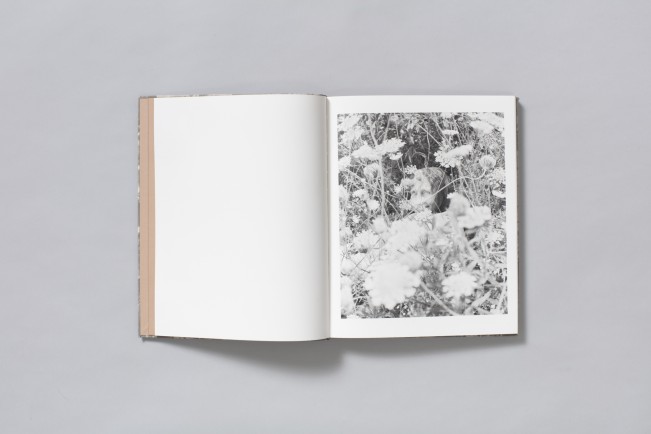

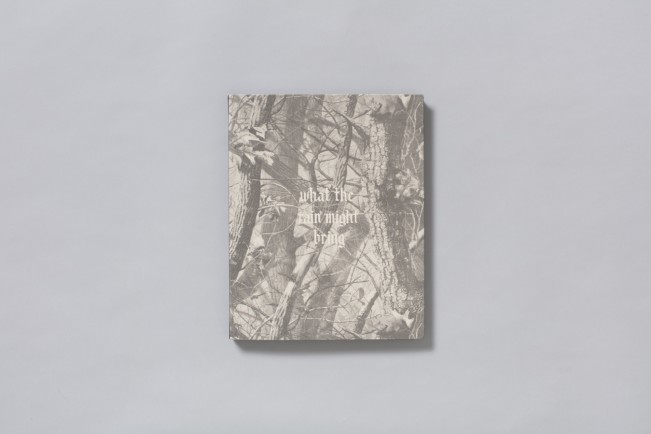

Named after David Arora’s mushroom identification guide, What The Rain Might Bring is a cross-disciplinary project that explores the complexities of storytelling, faith, folklore, and the inherent queerness of the natural world.

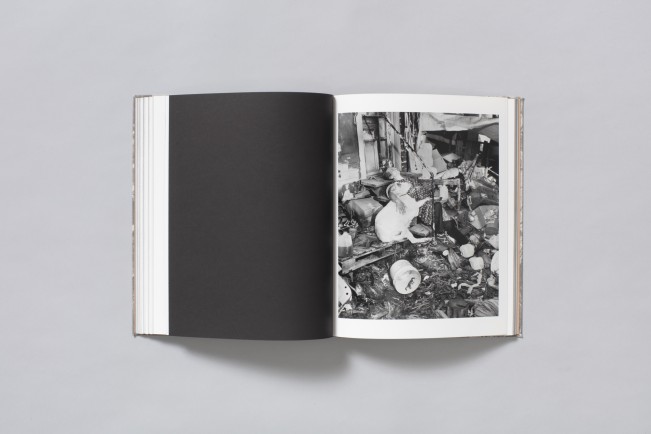

The often disregarded underbelly of a post-fact world seems to be the simultaneous beauty and danger of fiction. I’m interested in image-making as a process of hybridity—weavings of myth filled with tangents and nuances, treading the lines between investigative journalism, disinformation, performance, acts of obsession, and self-conscious manipulation. Photography’s ability to promote belief is a power not dissimilar to that of faith. By using modes of making that are traditionally linked to fact-finding, I hope for the viewers and readers of my work to find themselves in a space between fiction and reality—to push past questions of validity that form the base tradition of colonialism in storytelling and folklore and into a much more human sense of reality: faulted, broken, and real.”

– Dylan Hausthor, Artist Statement

Kicking things off, how much has What the Rain Might Bring changed and evolved from what you began at Yale?

It’s changed a lot… a couple of these pictures are from early grad school, but then I spent most of the time there doing different things—I made a movie and a few other books; then toward the end of school, I came back to this mode of making that felt more core. I wanted to crack open the eggshell in grad school, but after the yolk fell out I moved back into gluing its shell together and realized a new book was ready to hatch.

Were you still in school when you started talking with TBW about publishing the work?

Right after! We had a show in San Francisco and Paul Schiek was living in Oakland then. He invited me to dinner, I gave him this tiny little thesis book I made, and he was like, “This is ready for publishing.”

Then we’ve been working on it for freaking two or three years.

Building off that, can you talk about why you chose TBW and how your relationship with Paul developed?

Yeah, I love working with them. I’m really proud of everything that they’re doing, prioritizing art over everything—praising at the altar of storytelling, acknowledging the incredibly sticky world of art product-making, and being careful and intentional when wading through these sticky bogs of the photo book world. It has felt familiar and familial to make with them. It’s so deeply full of support and ego-less, branched-out love that feels so special to be part of.

Something I really love and appreciate about the book is seeing how so many of your past ideas and experiments have come together here.

For instance, thinking back to the barn, the French folds there feel as if they were precursors to the gate folds here in What the Rain Might Bring. Can you talk about how the book’s structure came about and how you drew on elements of past works?

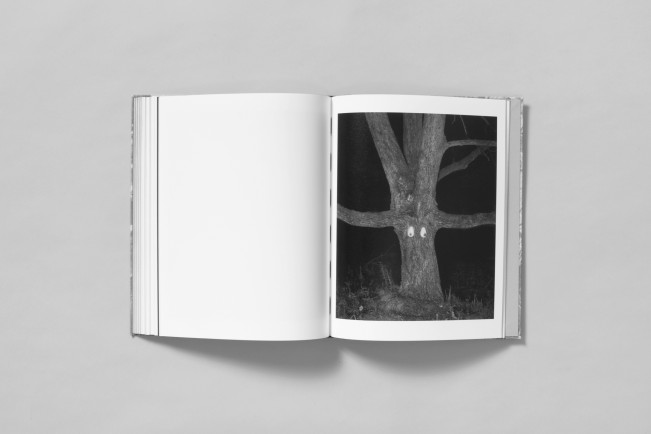

Yeah, I was thinking a lot about hiding, and withholding information or displaying information, which I think is really just like the practice of out-in-the-world photography.

Out-in-the-world image-making is a practice of displaying and withholding. Intermittently while making this, I was living within different religious communities—Mennonites, Mormons, Buddhists, Christian Monasteries, Shaker Villages, Pagans, and Utopic Communities in the Northeast. This led to thinking a lot about storytelling’s function in withholding and displaying… faith-based hiding.

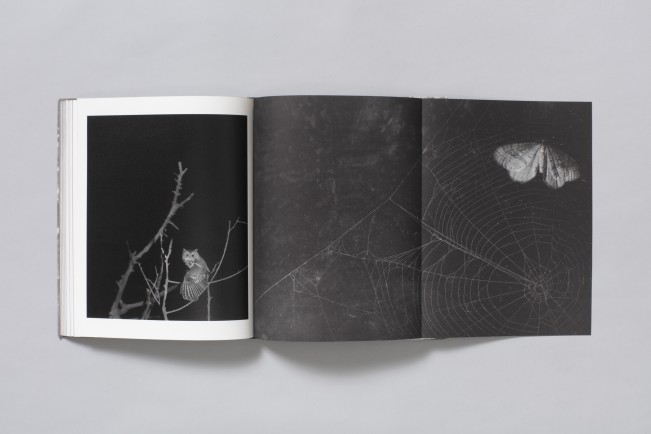

In the edit and the sequence, the book starts during the day, goes to the night, and does that seven times. Every time it’s about to become day again, there’s a gatefold. There are hidden symbols all over this book that a reader probably wouldn’t or shouldn’t notice while flipping through it. The gatefolds are so tight that they’re hard to open—I like the idea of using these past things that I’ve been interested in as symbols in storytelling.

We all want to disappear, we all want to hide.

How did the cover design come about? I feel like it’s the most “you” thing I can imagine *laughs* and I love the choice of a flexi-cover, it’s somewhere between a soft and hardcover book.

Yeah, we wanted people to throw them in their backpacks and treat them like mushroom hunting guides, we didn’t want it to be this sort of art object that’d end up on a coffee table. The realtree is just about hiding. Also, for me, it’s about the mode of making—hunting vs. fishing vs. growing.

All of the spider webs that are in every gatefold are also nodes to that. This creature has a sort of fraught ethical relationship to its consumption, as do I and photography.

I also like this idea of hiding and the trail camera. There are no trail camera pictures in the book, but the “capture” that was popularized by the trail camera also feels like this. The spider is just sort of waiting to consume, it’s like a fisherman, and I’m interested in photographers and makers also doing that. It’s not hunting, and is avoiding this sort of Sontagian violence and is more aligned with this like Arielle Azoulay’s interest in a sort of symbiosis with the thing that’s feeding you.

The type we made was inspired by the famous Voynich manuscript. It’s a type modeled after a Voynich script, which is this deeply mysterious, questionably cracked manuscript that like the existence, or seems to argue the existence, of a lot of mythical realities… it’s so interesting and I’m sort of obsessed with it as a source of bookmaking inspiration.

Also, on that topic of the book feeling like a reflection of you as a person; it almost mirrors how you present and perform as an artist. The images balance humor and their haunted, eerie nature really well. Can you talk about that relationship?

I don’t really think about it too much. I don’t really trust the idea of genre very much, it feels pretty antiquated.

I do trust how the way I move through the world affects people, and how the way that people move through the world affects me.

And that ends up being boobs on trees sometimes.

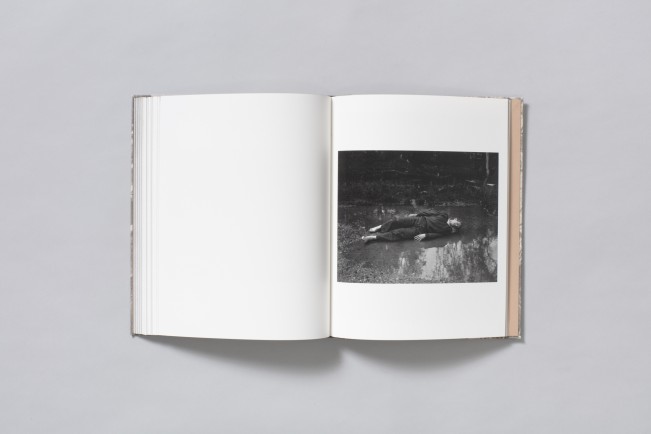

What’s your relationship to the people in the photographs? I recognize some of them as recurring “characters” throughout your work.

It’s a mix. A lot of them are from when I was living in those religious communities off and on during and post-COVID. Some of them are loved ones… a lot of them are loved ones… they’re all loved ones actually.

Do you put a lot of consideration into who you’re photographing?

I put more consideration into the dynamic of me being a photographer while it’s happening. A mentor at Yale talked about making images of a person as acts of love and I totally subscribed to that.

And so, it’s more about the dynamic in the room than it is the identity of the person. Although that shifts sometimes and their identity can be very important.

What led you to begin investigating queerness and its relationship to the land?

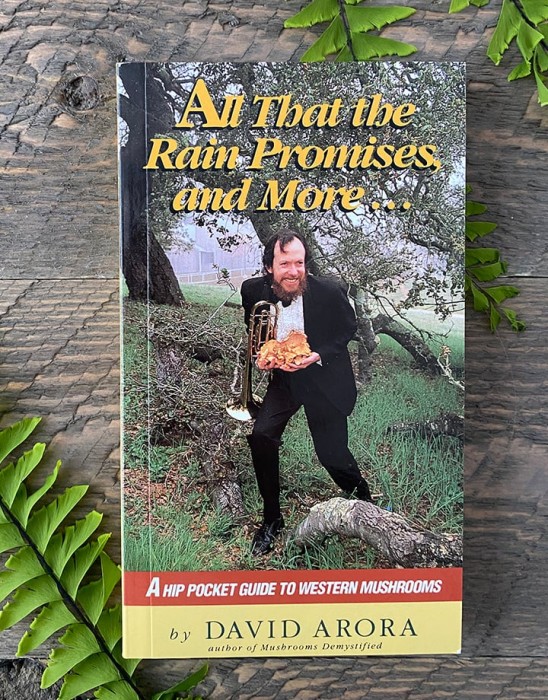

I think it was pretty largely inevitable. My own identity was part of it for sure—while I was thinking about these more vague ideas about hiding, revealing, and waiting. Observing beauty, and people’s relationship to that, I was also thinking about mycelium and how different species of mushrooms grow—the non-binary way that they reproduce. There’s a seminal mushroom book titled All the Rain Promises and More. Have you seen it?

I don’t think so, I’m not sure you’ve ever actually shown me it.

David Arora made it in the 70s I think, it has the best cover ever made.

That’s pretty amazing *laughs*

In it, he talks about mycophobia, it’s an easy leap to make between mycophobia and queerphobia. It’s sort of about fear, I think… fear of hate, desire to disappear, and the defiance that grows there.

In terms of specific subject matter or motif, fire has been so consistent in your work, is that something you’re actively thinking about?

Totally!

I wrote my undergrad thesis, and have based a lot of older work on a time when a neighbor of mine was very pregnant and set a mutual friend’s barn on fire. While it was burning she was asking for a ride to the hospital from her victim because her water broke as she was lighting it on fire.

I think that is just sort of a perfect symbol of why I’m interested in storytelling, and I’m interested in how people use fire as sources of heat, sources of safety, sources of cleansing, and also like really terrible violence and sadness.

I’m interested in extremes, and fire is that.

Also, in speaking about these formative moments, what sparked your fascination with photography as a faulted medium and an outlet for truth?

I mean, it’s just so broken, it’s the reason I love it.

I think about its total inability to be linear but still be moving through the world—photos in sequence existing as scenes, not a series of stories. When strung together, they’re like all of these warped sort of stories that seem to lead to horror or utopia so often. Specifically, just because of where we’re at, I’m thinking of political horror that seems like a symptom of just broken scenes.

How does the work change for you now that it’s a book?

I’m so glad it’s done and I’m ready for the next one. It feels done in a way that feels satisfying, that’s for sure.

Does it feel more true to what you’ve been envisioning compared to how you’ve installed it with newsprints, normal pigment prints… and I think you’ve done some fabric prints too?

Yeah! All of this work was always intended to be a book.

We also talk a lot about music and its influence on both our practices, is there anything you associate the most with this body of work?

Yeah, Grouper.

The album Ruins.

Can you talk about what you have next and maybe how the Guggenheim fellowship has allowed you to further your work?

Part of it was for finishing this work and now I’m working on this book that’s about angels, the history of angels, and my experience with angels… I don’t know how much I want to talk about it yet though.

I was raised as a combination of Agnostic, Reconstructionist, and Pagan, borderline Wiccan, and I’ve been thinking a lot about the power structures that are invested in all three of those modes of thinking and modes of moving through the world.

I’ve been thinking about how to use symbols, the angel in this case, as what seems like a mis-rendered icon of beautiful power. I’m deeply skeptical of power in all of its forms, but lord am I still looking for angels. If this last project was about hiding, I think I’m now interested in appearing.

What the Rain Might Bring

By Dylan Hausthor

Published by TBW Books

Click for more information, to see additional images, or to purchase a copy of the book.

Dylan Hausthor is an artist based between the midcoast and an island off the coast of Maine. They received their BFA from Maine College of Art and MFA from Yale School of Art. They were a 2019 recipient of a Nancy Graves fellowship for visual artists, runner-up for the Aperture Portfolio Prize, nominated for Prix Pictet 2021, a W. Eugene Smith Grant finalist, 2021 Hariban Award Honorable Mention, 2021 Penumbra Foundation resident, 2023 Light Work resident, and the winner of Burn Magazine’s Emerging Photographer’s Fund.

Their work has been shown nationally and internationally, and they have three books in the permanent collection at MoMA. They work teaching ghost hunting, ritual, photography, and mushroom foraging.

To help write this biography, Dylan contacted a forensic medium, who suggested that they “seemed like someone who was passionate in the things they believed in, hides secret messages in the things they have to say, and should avoid driving Volvos”.

They are a 2024 Guggenheim Fellow.

Follow Dylan:

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Shane Hallinan: The 2025 Salon Jane Award WinnerFebruary 12th, 2026

-

Michael O. Snyder: Alleghania, A Central Appalachian Folklore AnthologyJanuary 18th, 2026

-

David Katzenstein: BrownieJanuary 11th, 2026

-

Amani Willet: Invisible SunJanuary 10th, 2026

-

THE 2025 LENSCRATCH STAFF FAVORITE THINGSDecember 30th, 2025