Photographers on Photographers: Meg Griffiths and Cig Harvey in Conversation

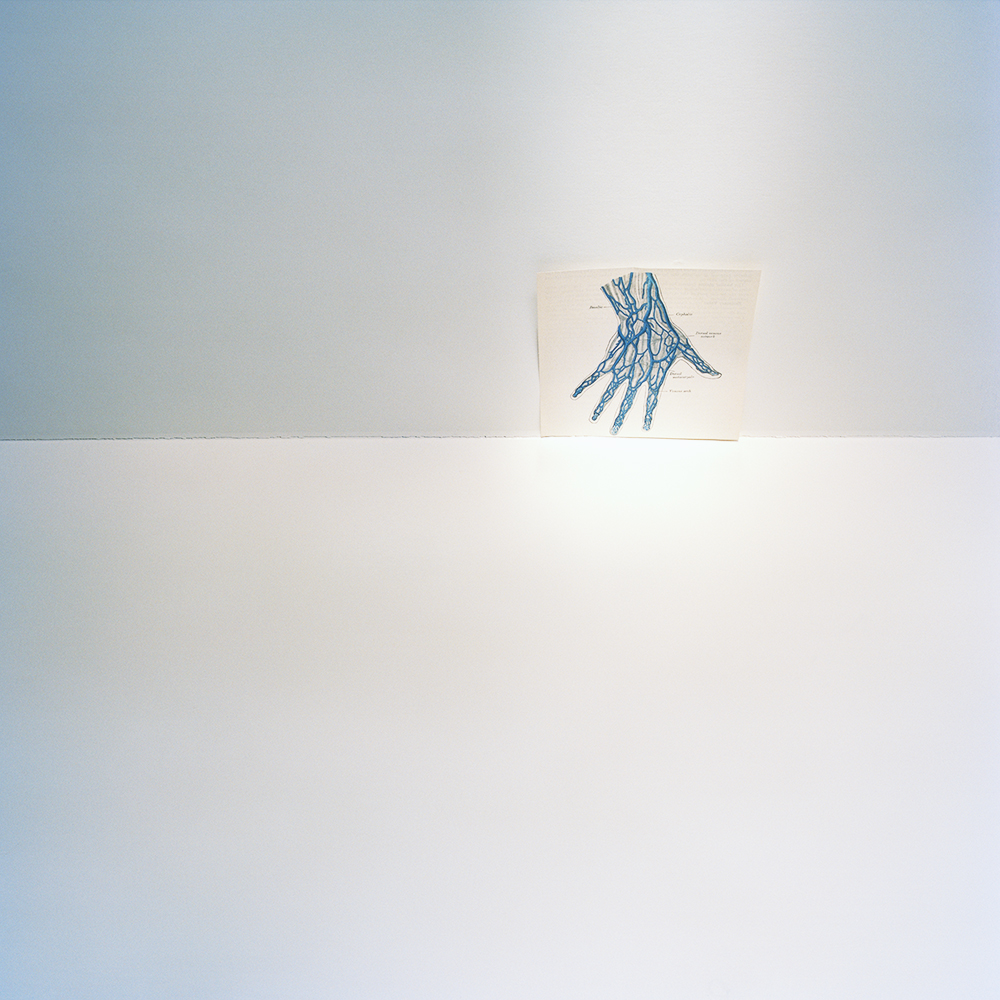

©Meg Griffiths, Sieve of the Universe form the series Somewhere Within and Without, 2017, Archival Inkjet Print

Today ends a month of amazing interviews by photographers on photographers, and I am thrilled to finish the series with two women I so admire, Cig Harvey and Meg Griffiths. We are honored that they are sharing new work, some never published previously. I am also grateful to all the photographers who participated this month–so appreciative of the time and effort extended by all. – Aline Smithson

I first met Cig Harvey in the summer of 2008 at Maine Media Workshops + College. Her class—which still runs full every summer—The Personal Story was something I had wanted to do since seeing her work for the first time back in 2007 at a show that one of my Professor Nine Francois had taken me to as part of a class field trip. From the moment I clasped eyes on her series Eyes like Disappointed Lemons my perception of photography quite literally shifted. “I didn’t know photography could be like that,” I kept saying to Nine. I was simply enchanted. I can honestly say that this show and her class marked two very important moments in my life, and like guides from the universe, a couple of many I would have along the way, they nudged me toward the place I am today.

It was my absolute honor to write a letter nominating her for the 2017 Excellence in Teaching Award at Center in Santa Fe, one of just many I am sure who wrote how she inspired and changed their lives. Now again, it is my delight to interview her, sharing a bit of conversation and some photo exchanges we have had for the past month—talking about inspiration, the process, motherhood and balance.

Cig Harvey (born 1973) is a photographer/writer whose practice seeks to find the magical in everyday life. Rich in implied narrative, Harvey’s work is deeply rooted in the natural environment, and offers explorations of belonging and familial relationships. She is the author of three sold-out books, You Look At Me Like An Emergency (Schilt Publishing, 2012), Gardening at Night (Schilt Publishing, 2015) and You an Orchestra You a Bomb, 2017).

Cig Harvey (born 1973) is a photographer/writer whose practice seeks to find the magical in everyday life. Rich in implied narrative, Harvey’s work is deeply rooted in the natural environment, and offers explorations of belonging and familial relationships. She is the author of three sold-out books, You Look At Me Like An Emergency (Schilt Publishing, 2012), Gardening at Night (Schilt Publishing, 2015) and You an Orchestra You a Bomb, 2017).

She is represented by Robert Mann gallery in New York, Huxley-Parlour gallery in the UK, Joel Soroka gallery in Aspen, Robert Klein gallery in Boston, Kopeikin gallery in Los Angeles, Photo Eye in Santa Fe – See more of her work at cigharvey.com and follow her @cig_harvey

Meg Griffiths (born in 1980) is a Texas based artist who’s work deals with domestic, economic, historical and cultural relationships across the Southern United States and Cuba. Her work has been shown internationally, including: Pingyao International Festival of Photography, Chaing Mai Photo Festival, at venues such as Columbia Museum of Art, Center for Fine Art Photography, Museum of Living Artists in San Diego, Griffin Museum in Boston, Houston Center for Photography, and is scheduled for the 5th Biennial of Fine Art and Documentary Photography in Barcelona, Spain and Filter Photographic Festival in the Fall of 2018. She has also been published in the Boston Globe, Photo District News and most recently featured on the cover of Oxford American Magazine. Her work is a part of many private collections as well as the Capitol One Collection, Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, the Center for Fine Art Photography and now the MOMA book collection. She was selected as one of PDN’s 30 to watch in 2012, Atlanta Celebrates Photography’s One’s to Watch in 2016, and honored to receive one of the Julia Margaret Cameron Awards for Best Fine Art Photography in 2017. Meg’s publications a monograph entitled Casas de fruta y pan published in 2015, and more recently a collaboration with fellow photographer and educator Eliot Dudik entitled Nothing that Falls Away with Zatara Press in 2018.

She is currently an Assistant Professor of Photography and Area Head of Photography at Texas Woman’s University in Denton, Texas.

©Meg Griffiths and Eliot Dudik, Nothing That Falls Away, Published by Zatara Press and available for Pre-Order

©Cig Harvey, you an Orchestra, you a Bomb, published by Schilt Publishing

Meg Griffiths: What was your sense of play as a child and how do you see this revealing itself in your images?

Cig Harvey: My sense of play as a kid is my art practice now. As a child, I remember dragging my grandmother’s chair to the bottom of the driveway, sitting down and watching the world go by. We lived in a cul-de-sac, eight A-frame identical houses. My sister’s room front top left, mine top right, my parents in the back over looking the train tracks. The chair is embroidered with flowers and birds. It is scratchy. My family hates it but I love it. Conjuring this vivid sensory memory is a big part of my work today.

My mum would sometimes drink gin and tonics and smoke cigarettes with big Sarah’s mum in the late afternoon. They lived two down and we would dash across the in-between neighbor’s garden. My mum grew roses and we would cut them with scissors, mixing their petals with water and oil to make perfume. I would sell it on my stand at the bottom of the driveway. Brown lumpy water that smells of deep love. I remember this cul-de-sac but nothing of the road before or after, like the world dropped away right at that corner.

Cig Harvey: What are you obsessing about right now? and do you see that concern coming out in your pictures?

Meg Griffiths: I had a residency at the Vermont Studio Center this past May. I decided to drive up from Texas. On the way I stopped off at this antique store in Texarkana called the Vintage Bucket. Tucked away in the farthest booth I stumbled across some old Nat Geo Magazines. They were bound by year. Intrigued, I grabbed the stack from the year I was born and went to check out. Ringing me up the woman behind the counter commented, “these are quite old, older than you, now what you gonna do with these darlin’?” I smiled and explained they were actually from my birth year and I was hoping for inspiration. She said “oh sweet heart, don’t you know never to reveal your age.” I didn’t think much of this at the time, except to respond warmly, “and here I was thinking that was still young.”

I suppose I have always been obsessed with the quotidian, the everyday, the domestic, and interactions with people—how this all comes to play in my work. While in Vermont I found myself walking to the grocery store a lot to, take a break, but also in search for things to include in my pieces. I became fascinated with common household objects, and the process of using them as a means of meditation and revelation. Mundane things like sandwich bags your peanut butter and jelly came in as a kid or twisty ties. How performing simple tasks with these things over and over can become transfixing, soothing, and introspective. It was in the process of making with these objects that I found myself thinking about my life. What I remembered and what it was full of, the weight of that. I am now, a bit fixated on waterfalls. As bodies of water, as a play on words, as metaphors and how they are abstracted, what all that means to me right now.

MG: How do you define inspiration? In what ways do you go about accessing it? How do you know when you have?

CH: I love your response Meg.

You and I are similar, in that we both share the everyday as our main source of inspiration. I think we are lucky; trying to find beauty in ordinary routine is a good way to live a life. It keeps me connected to nature, up at dawn and out at dusk. And it makes me appreciate and treasure the world around me.

When it comes to inspiration, I trust my instincts a lot. If I am drawn to a certain person, or place, or object or color, I make pictures first and question why afterwards. I sit and have a date night with my photographs. I listen to what they are trying to tell me, and I write a lot to better understand why I am drawn to certain things. It can be a wonderful union of instinct and thoughtful discourse. Ideas are often word-based, so assigning language can help reach a greater understanding in our practice.

Right now I am exploring the senses in my work. In particular, the senses in relation to color and memory. I am interested in the immediate reaction, how the body physically responds before intellectual thought. It is definitely a work in progress.

CH: Tell me more about the photographs you sent me! How are you going about constructing them?

MG: I completely agree, it is all a work in progress. I feel this way in perpetuity about everything!

Right now, I like to think of myself as a gatherer. I go out and forage and then bring things back to the studio. Often foraging by reading literature and poetry. Other times it takes form in the objects I have mined locally from junk shops or antique stores. Some of the material in these pieces I’d brought with me from Texas to Vermont, like the snake skins, excavated from old magazines, or purchased from the market down the road.

Sitting in my studio one afternoon I began to pluck bags from a box and fill them up with water. I’d walk to the sink, fill it, walk back, sit down, gather up the end, twirl it around, and tie it up tight. Each time I would contemplate a year of my life. Trying to remember things that year—what was hard, joyful, challenging, painful, what I was grateful for. Then I’d pin it up on the wall. I did this again and again. It felt natural to allow myself to get lost in the physical activity, to give into just being with material while meditating on what those years held for me. I enjoyed the process of remembering, putting that somewhere, then pinning it up, looking at it, and reflecting. They are very emotional pieces. Their source; coming from various arteries, they touch and move across vast terrain, then welling up into one flowing body, they disperse.

MG: Do you ever feel like anything is really finished? At what point do you look at an image or reflect upon it enough to say, this is ready to be out in the world? What image have you made recently that you are in love with right now?

CH: I am the same way about foraging. It is absolutely a part of my creative process. I often gravitate towards certain colors and objects and have to surround myself with them by painting walls, creating little altars, living with these objects. Sometimes when I get stuck, I give myself a small budget and head to a vintage store to find something that speaks to my work. The deal I make with myself is that I have to make a picture of it THAT day. And then, you now how it goes, pictures make more pictures, the cycle of making continues; make, see, listen, make, see, listen.

Right now my new work is an exploration of the senses and memory so I am trying to surround myself with things that smell, feel, sound, taste and look a certain way. I have a small curved dish of the palest pink waxed rose petals in front of me right now. They smell, look and feel amazing.

Do I ever feel like anything is ever finished? You know the thread continues but I do feel that my work comes in chapters or projects. I become obsessed with one idea and then after I have explored it both visually and intellectually, I move on. The pictures are obviously connected to images I have made earlier but the story is new within each project. That is what keeps me so in love with this medium and the creative process in general.

CH: What do you see as being the central themes in your work?

MG: I love your process. I feel like that is such an amazing challenge and a productive parameter to set for yourself. This ensures that you explore the possibilities of your connection to that object while fresh. Just hearing about this way of working feels very present and inspiring.

Central themes within my work all concern family and connection, whether that be to others, or the self, or community. Each body of work attempts to deconstruct perception in some way, and it usually begins with a question or a desire to try to understand what is unknown to me. Making these pictures or installations is a way for me to come to certain answers, or, as you put it, a place to move from into the next thing—whatever that may be, but it is all connected. And it is a learning process. These themes reveal themselves through an intimate exploration of the domestic. Recently, they have surfaced through more abstract introspections on space and time, being and not being, and the metaphysical nature of personal historical identity.

MG: You were recently featured in the New York Times and asked to make work using a poem entitled “Edge” by Layli Long Soldier as inspiration. I absolutely loved this collaboration between you and your daughter. How do you feel being a mother has changed the way that you work or how you perceive the world?

CH: Yes it was a dream assignment for sure. I loved the whole thing. So inspiring to see how other photographers visually responded to the poems.

Becoming a mother has made me a better photographer. Becoming a mother is complicated and all of those feelings are reflected in my work. I have never felt such love or such fear. I think my job as a mother is to keep Scout safe, but also to get out of her way. I learn so much from her. I love seeing the world through her eyes. Like photography itself, she makes me appreciate the world more. I try and show that in the pictures. The way she lives, so sensory and immediate is inspiring.

In reality, I probably make less pictures of my daughter than most people do of their kids. I try to keep the camera for when something extraordinary is happening, or for when I’m ready to really craft an image. I want to keep the act of photographing exciting and creative for her rather than erhhhhh…Mummy’s out taking pictures of me again, insert eye roll…

She makes up maybe 25% of my new work but they are some of my favorites.

CH: Talk to me about you becoming a mother. I didn’t even realize you were pregnant until fairly late in your pregnancy.

MG: They are some of my favorites too.

Oh my, well becoming a mother was such a process for me. I always wanted to be a mother. I had planned that I would “some day” when I had all my ducks in a row. Then I got pregnant and it was not planned. All my ducks were not even there, let alone in a row. There was a rush of very mixed emotions. The decision to hold back sharing was really two fold: I needed a better job to provide for my son and I wanted to protect my art career. In a different way I felt the instinct to keep things safe, even before Oliver arrived.

I was on the market the year I got pregnant, an academic—at the time holding an adjunct salary (we are talking less than $6,000 per semester) with no benefits. I was applying for jobs, getting interviews, going on campus visits. As much as I would like to believe that people would not be biased or non-discriminatory, I just could not take the chance that I may not get a job because I was pregnant. Even more so because I was set to have him 6 weeks before the following school year would begin. So I did not share that information publicly to protect that potential means of supporting my family.

I also think it is particularly hard to be an artist and a mother. Starting in grad school I’d hear people (both men and women) say some iteration of “she was a really amazing artist, then she went off and had a baby.” Like it is a cautionary tale. As if somehow choosing to take time to make a human is literally the death knell of your art career. I felt very strongly at the time that if people were going to talk about me, then it was going to be about my work and my passion for teaching. I chose to keep it all close to my chest.

In hindsight I would have landed on my feet exactly where I was supposed to be, but honestly there is nothing like the purpose of being a mother. You get more focused on the things that are important and you get really organized with your time. And now I have a brilliant, healthy, beautiful son—the most amazing thing I have ever done, a job teaching and I still get to make pictures too 😉

MG: Can you talk a little bit about those moments that are challenging? Or times where you find it hard to make? How do you work through this?

CH: Oh Meg, I remember hearing that same cautionary tale when I was pregnant and feeling exactly as you did. It made me very defensive. In fact, I have never felt as judged in all aspects of my life as when I was pregnant and during Scout’s first year. I didn’t want feel that way, but I did.

Managing the daily schedule can still be a real challenge. Sometimes I dream of an entire weekend spent in the studio, remember those morning-to-night sessions of uninterrupted creative time? I would literally spend 16 hours straight in the darkroom back in the day. But the struggles are always out weighed by the deep love. I feel lucky to be Scout’s mum. I am also aware of how quickly time is passing. She is already seven, in a few years she will be a teenager and hating me;) Got to enjoy every second of today.

When I get stuck creatively, it is normally because I am not giving my work enough time and space. So I try to get up earlier and write at dawn while everyone is still sleeping. That is my power time. I have never been a night owl. I write to access ideas and my best ideas happen first thing. Sometimes I feel like I can accomplish an entire day’s work between 5 and 9am. Lizzie, my commercial agent, had a kid around the same time as did, and often we would be emailing each other contracts at 2 a.m. and she was like, huh, so this is when Moms get it all done. People often ask me about how to balance life and art and I say I have no idea, that it’s always a work in progress.

CH: How do you balance it?

MG: That is such a hard question to answer. Do I even believe in balance? I don’t know. I think it is this state of being that we all strive for and we all talk about, but is it really possible? Or even very realistic? Balance is a great goal in theory, but if the path to get there is dissatisfaction that my life is not there, and may never be, then maybe restructuring things is a more productive and positive use of my time.

Right now I am more interested in working toward being good with the fact that my life does not exist in that state and that this is ok. I do this by getting really organized about time, just as it sounds like you do. I try to carve out concentrated spaces for various things and I work at being present and grateful for that time while I am in it, whether that with my son, in the studio, or in the classroom. I can only be, where I am at. The more complicated life becomes the more I find that I have to really make that time for all these things, even if that time is never seems like enough, it is what I can make. Now does that mean balance? It almost never feels like balance. I do believe that I can have all of what I want in life, however I do not think I can have it all at the same time. I am good with this reality. Maybe there is some alternate universe where equilibrium is the norm and imbalance is the anomaly. Wouldn’t that be something? Gosh you have to wonder what that would look like.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Margo Ovcharenko: OvertimeJanuary 27th, 2026

-

Yumi Janairo Roth: EFFIGY 1462January 20th, 2026

-

Nathan Bolton in Conversation with Douglas BreaultJanuary 3rd, 2026