BEYOND THE PHOTOGRAPH: Q&A WITH PHOTO EDITOR JESSIE WENDER, THE NEW YORK TIMES

© Camila Falquez and The New York Times. Manuel Liñán and company photographed for the Culture section.

Beyond the Photograph is a Lenscratch Magazine monthly series dedicated to helping photographers grow their artistic practices beyond the camera. Capturing images is just one small part of a photographer’s journey. In this series, we’ll explore the tools, strategies, and best practices that support the broader aspects of a contemporary art career.

In the last edition, we had the opportunity to look at editorial work through the eyes of one photographer, Tamara Reynolds. This month, we get to learn about the other side of the equation from photo editor Jessie Wender at The New York Times, on the Opinion desk. She has been a photo editor for almost 20 years, starting at Time Inc., where she worked on custom publications on topics ranging from casinos (!!!) to National Parks. Most of her career has been at The New Yorker and at The New York Times. She has also worked at National Geographic, Apple, and Esquire. She started at The Times as a photo editor on the Archival Storytelling desk and then transferred to Arts and Culture. In 2022, she moved to the Opinion desk and has been a photo editor there for the past three years.

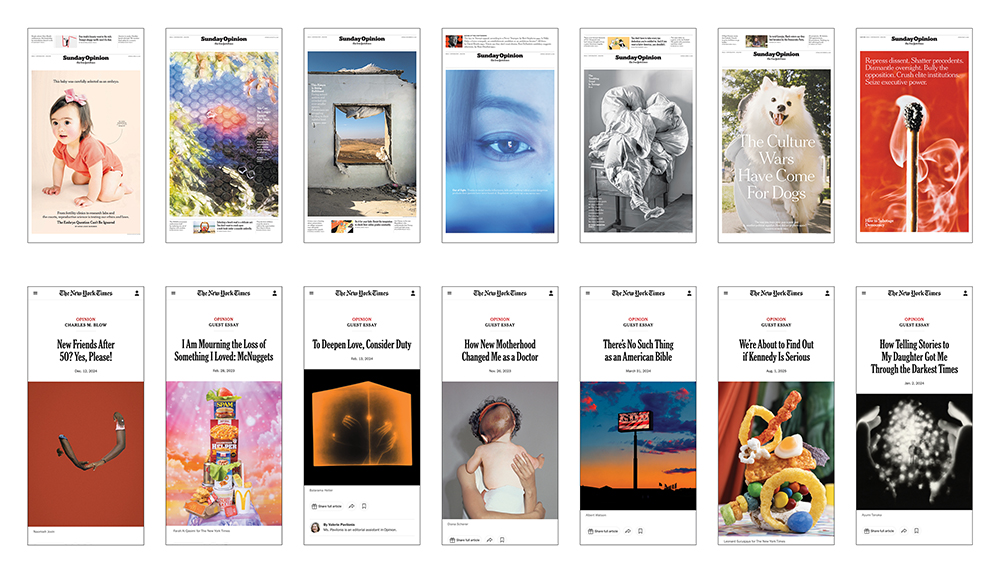

© The photographer and The New York Times. A selection of commissions and research for the Opinion section, top row photographs by Dru Donovan, Rosie Clements, Samar Hazboun, Jason Nocito, Carolyn Drake, Mark Peckmezian and Philotheus Nisch. Bottom row photographs by: Naomieh Jovin, Farah Al Qasimi, Balarama Heller, Diana Scherer, Albert Watson, Leonard Suryajaya and Ayumi Tanaka.

Q: How do you find photographers and learn about their work? Is it through the photo reviews, word-of-mouth, and/or other ways?

Well, I’m currently on the Opinion desk, and because the visuals do not have to fit strictly within the realm of reportage, my research and assigning can be expansive enough to open the door to fine art photography.

I do a lot of my research on Instagram and by following sites that promote photographers’ personal projects like Lenscratch, PH Museum, Aperture, Foam, Der Greif, Humble Arts Foundation, and many others. I love when I can commission or publish work by a photographer whose personal work intersects with the subjects of stories I’m assigning or researching.

Reviews, awards and residencies are great too. I work with amazing colleagues, who introduce me to new photographers every day. Sites that let you search by location, like Women Photograph and Diversify, are also super helpful.

Q: Do photographers still send self-promo pieces to you? If so, do you think they are effective? Or has our digital world changed the process permanently?

When I was working at The New Yorker, almost fifteen years ago, I had a “wall of inspiration,” where I collected beautiful promos as reminders of photographers I wanted to work with. Now I use a (less inspirational, but very functional) spreadsheet.

Photographers sometimes mail promos to me, but I don’t think they are any more compelling than reaching out digitally. One of the most effective ways to reach out to editors, is to send a personal note. When doing so, it is important to have a sense of how your work could align with that editor’s publication. It’s great to send an update several times a year with your whereabouts, sharing new work, and saying “Hey, I saw this thing you published, and it was awesome. I’d love to do something like that for you.”

I try to respond to the personalized emails I receive, but I usually don’t open email blasts, and sadly I no longer have a wall to save promos.

Q: When you are looking for a photographer for a particular assignment, what does that process look like for you?

On the Opinion desk at The New York Times, the subjects for our essays really span everything from politics to culture, environment to education, and more creative features and takes. That’s to say we work with a wide range of photographers. Many of our Opinion essays are conceptual in nature and rooted in a point of view or argument. We’re always looking for photographers whose work reflects that and has a less literal or metaphorical approach.

Geography plays a huge role when I’m looking for a photographer. Often, I’m looking for a photographer who is local, or has a connection to a specific place.

I also consider the subject matter of the essay and how that that relates to a photographer’s work. Does a photographer focus on a specific subject, or perhaps a body of work exploring the opposing argument. I often try to think about photographers’ personal interests or background that would be interesting to pair with the subject matter in an editorial context.

I also consider the photographer’s style and aesthetic approach and how that relates to the subject of an essay. Does someone have a bright and pop-y style that would be fun to pair with a still life, or perhaps a more tactile collage approach? We have a lot of stories that are difficult to visualize creatively, so we’re often looking to work with photographers who have an artistic approach that can be applied to different topics in a less literal way.

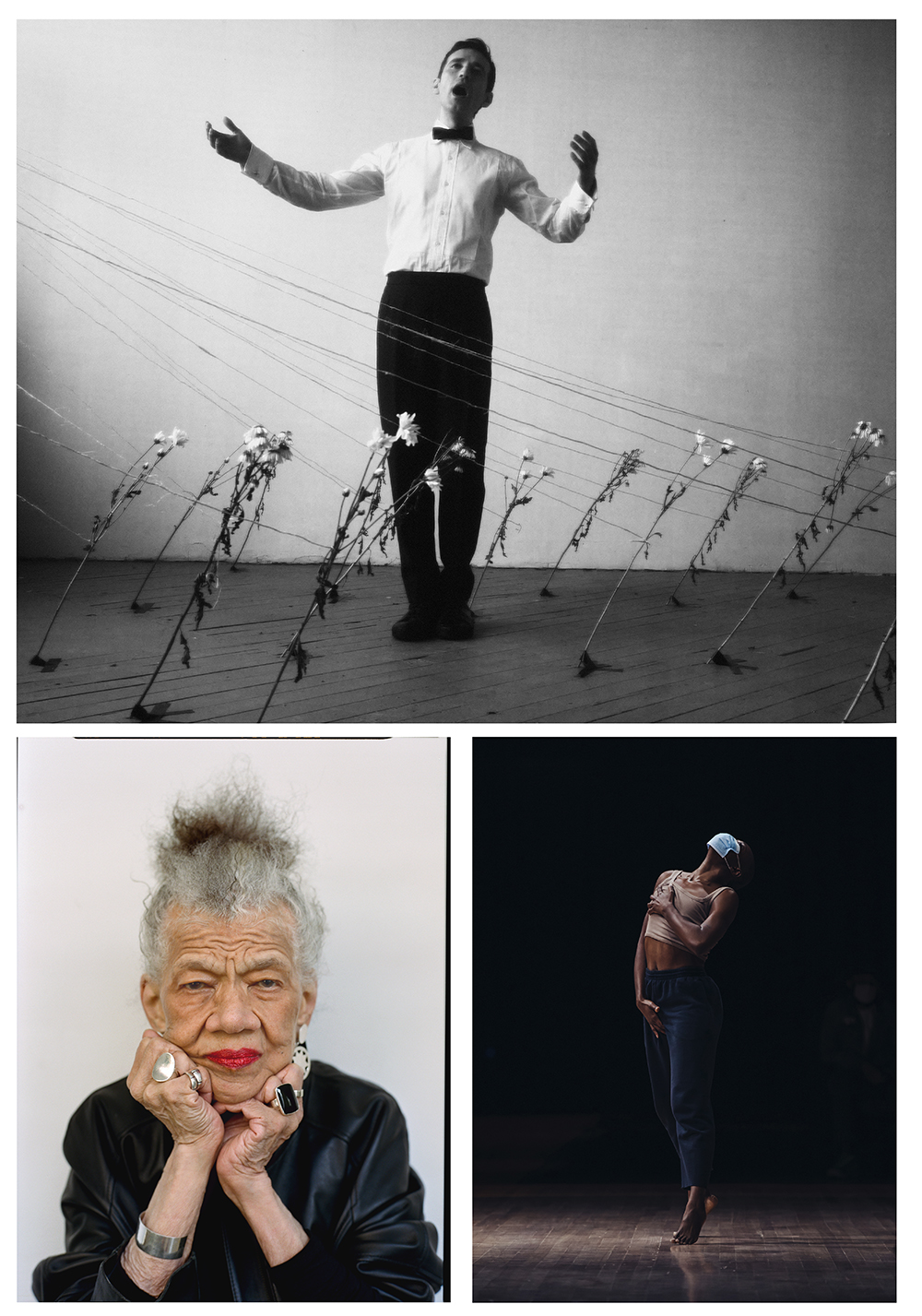

© The photographer and The New York Times. Portraits for the Culture section clockwise from top: Anthony Roth Costanzo by Erik Tanner; Afterwardness by Sasha Arutyunova; and Lorainne O’Grady by Lelanie Foster.

Q: What does an editorial contract look like?

Every publication has different terms. It’s important for photographers to read and understand the contract they are signing. Contracts typically include information about copyright of the photos, exclusivity agreements, and future use. In my experience, there is no or very little room to negotiate contracts.

Q: What do editorial assignment fees entail and how are they set? Are they billed by assignment, day rate, is there a travel per diem, or other important information?

Day rates differ from publication to publication. The Times has set day rates, travel days, assistant rates, mileage rates, and food rates. It’s an effort to be equitable, transparent and consistent. The fees are really assignment specific. For example, typical costs for a local portrait assignment include transportation and mileage and a day rate. For a more extensive or complicated assignment, costs might include multiple day rates, an assistant, travel days, lodging, food, and other expenses.

Q: Can you explain how usage fees work? Are there buy outs, or exclusive rights?

The Times has a standard licensing agreement for existing work. We have pretty set usage fees. But the amount can range depending on placement—if the image is running online only, in the body of an essay, or as the cover of a section. I have never done a “buy out,” but I do often try to confirm an exclusive period.

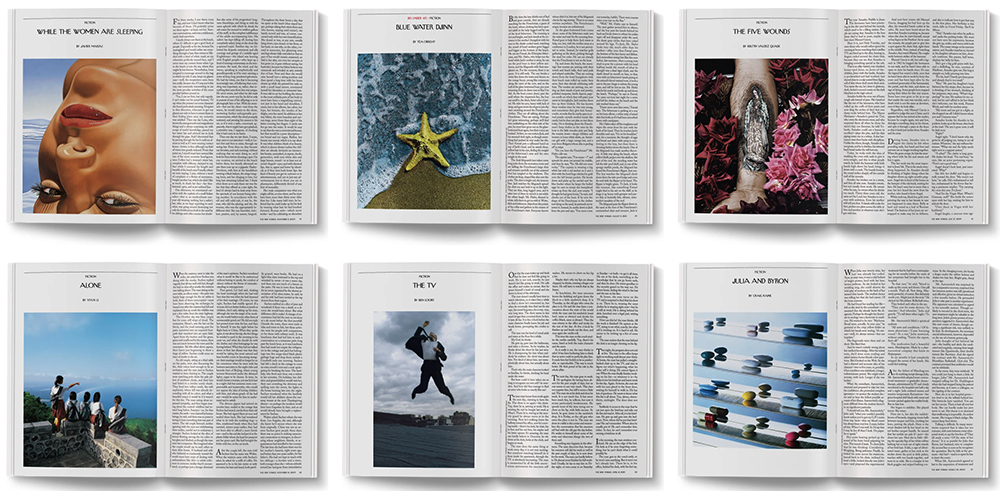

© The photographer and The New Yorker. Researched images for the fiction section clockwise from top left: Richard Phillips, Youssef Nabil, Delilah Montoya, Damien Hirst, Robert Longo, and Weng Fen.

Q: How collaborative is the process between you and a photographer for editorial assignments?

I usually hire a specific photographer because I want to see their personal approach and aesthetic reflected in the images. So, in that way the creative approach is collaborative. I encourage photographers to take the “safe” photographs, but also want them to get creative and try more unusual and daring things that excite them. We’re generally working within the bounds of an essay’s subject, but I usually find that is a helpful framework.

When time permits, I love to get feedback on edits. When I was at National Geographic, the editing process was very collaborative. A photographer would submit their FULL take—often over 50,000 images, I would make an edit, and the photographer would make an edit, then we’d combine our selects and determine the final edit. At The Times, our stories usually move much more quickly, but I love taking a photographer’s favorite photos into consideration when there’s time.

© The photographer and The New Yorker. Commissioned images clockwise from top left: Sharon Jones photographed by Ruven Afanador, Questlove image by Kehinde Wiley, Taylor Swift photographed by Katy Grannan, The Cast of Pan Am photographed by Sylvia Plachy, Dirty Martini photographed by Pari Dukovic, and Sheila Heti photographed by Ethan Levitas.

Q: Have you, or the writer, ever been present during an assignment?

It’s rare that I am on set. For the most part, my hope is to hire a photographer to do their thing, and provide the best possible circumstances for them to do so without my being present. I think the intimacy between a photographer and subject can be really powerful. But depending on the story, it can be very helpful to have photo editors present to manage publicists, subjects, or to give art direction.

Writers and photographers often work together when reporting from the field. Some writers prefer to report without photographers present, or photographers prefer to photograph without writers there, so they can have time solely dedicated to photography. There can be benefits and downsides to both approaches, and it also depends on the type of story—is it a thoughtful portrait, reporting out in the field, a highly styled fashion shoot, or some other scenario.

© The photographer and The New York Times. Photographs for the Opinion section clockwise from top left: Malin Fezehai on the impact of foreign aid cuts. William Keo on Syrian Migration. Lindokuhle Sobekwa on South Africa’s elections.

Q: Have you ever had a photographer successfully pitch a story idea to you that ran?

Yes! It can be challenging, especially in a relentless news cycle, but I love getting pitches from photographers. I also try to stay up to date on photographers’ projects and reach out when their work could be a good fit for the Opinion page.

When photographers are pitching a story to photo editors, one of the most important things is to know the magazine/newspaper section/platform you are pitching to. For Opinion, when we receive photographer’s essays, even if we love the photographs, the first thing we’re asking is—is this a good fit for us? What is the argument, or point of view?

In a pitch, I think there are several key points to convey—What is the thesis of the project? Why is it important now? Why should readers care? What does the photographer bring to the essay? Why is it important to hear about this issue from you, specifically? And, of course the visuals are key.

© The photographer and The New York Times. A selection of photographer projects from left: Adam Rouhana on photographing Palestinian Life, Will Matsuda on the trees that survived Hiroshima, Camila Falquez on Indigenous climate activists, and Charlotte Drury on the Olympics and trampoline.

Jessie Wender is a photo editor, writer and producer. She has worked in the photo departments of The New York Times, Apple, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Esquire and Time Inc. She loves working with artists, with creative people, and supporting emerging photographers. Her photographs have been published in The New Yorker and MIT Technology Review. Jessie has written for The New York Times, The New Yorker, National Geographic, Contact Sheet, and Rose Issa Projects. Her commissions have been recognized by American Photography, American Society of Magazine Editors, Society for News Design and Society of Publication Designers.

Jeanine Michna-Bales

After a successful 20-year career as a creative in advertising, Jeanine Michna-Bales transitioned to become a full-time artist. A visual storyteller working primarily in photography, Michna-Bales (American, b. 1971) explores the profound impact of cornerstone relationships on contemporary society—the connections between individuals, communities, and the land we inhabit. Her work sits at the crossroads of curiosity and knowledge, blending documentary and fine art, past and present, and disciplines like anthropology, sociology, environmentalism, and activism.

Michna-Bales’ artistic practice is rooted in thorough, often primary-source research, which allows her to explore multiple perspectives, grasp the complexities of cause and effect, and understand the socio-political context surrounding the subjects she examines.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Spotlight on the Photographic Arts Council Los AngelesNovember 23rd, 2025

-

100 Years of the Photobooth: Celebrating Vintage Analog PhotoboothsNovember 12th, 2025

-

100 Years of the Photobooth: The Photobooth Technicians ProjectNovember 11th, 2025

-

100 Years of the Photobooth: Rafael Hortala-Vallve: AUTOFOTONovember 10th, 2025

-

BEYOND THE PHOTOGRAPH: Q&A WITH PHOTO EDITOR JESSIE WENDER, THE NEW YORK TIMESAugust 22nd, 2025