Interview with Dylan Hausthor: The Barn, Queer Futurism, and New England Gas Stations

Back in November of 2023, I spent a day with Dylan and had the privilege of helping with some of the printing and production of the barn. It’s a really special project and such a beautiful handmade book. Being such a big fan of Dylan and their work, it only felt natural to sit down and dig into it a little more. So we met up the next month to have the following conversation.

I’m incredibly thankful for both opportunities and for getting to know Dylan over the past year. They’re someone I’ve looked up to for several years and it’s been a little surreal to now have them be a part of life as both a friend and a mentor figure.

For starters, can you talk a little bit about the barn as a subject matter, and what attracted you to it?

Oh sure! I’ve been deep in a multiyear project that feels like a post-grad school return to my interest in post-document… well, that’s not true… not post-document, but using the world as a way of working through imagination and storytelling. It’s been a big project that’s finally coming to an end, and that’s what the rain might bring.

And so, I was in the middle of that mode of making while also doing a residency, which is how I got access to this barn last summer. It felt like a space that I could use to make images that would work for that project, but then I was like – “what if I just commit to this barn, and use these couple of rooms as a stage for imagination, instead of working with the world. What if I just forced everything that I was interested in into this space?” It feels selfish and personal… but in a nice way.

When making this body of work do you feel as though you took on more of a directorial role then?

Well, I guess something I was thinking about at the end of grad school is just the function of imagination in contemporary art. It just feels sort of like a pendulum swinging from interest in the post-document to identity-driven work, and I’m not so interested in identity as a catalyst for making. I am interested in imagination as a sort of response to culture though, and I think imagination and directing have some sort of relationship.

I feel like from just the text that’s in the book, and looking at the images, the barn is more of an entity than simply a set… what do you think of it? Like is it just a stage… or is it something more?

The first title for this was praying in the barn and I think that’s how I think of it. It’s like a church… the barn is a cathedral.

Outside of just being a space, it feels like a place with which to plop things onto. Like faith and feelings… it feels like a church.

Did the confines of working in the barn evolve your practice outside of this? Like has it shaped you as a maker in any new ways?

No, not at all.

Like now I’m working on this project that has nothing to do with anything I’ve been thinking about. It’s these super… I’m still not sure what’s going on in this work… But it’s all super saturated, really bright color investigations of insects *laughs* I don’t know what’s happening…

Actually… that’s not true. It’s mostly about angels! I realized that the other day. The project I’m working on now is all about angels. Angels and bugs!

Angels and bugs? How are they connected?

I think they’re kinda the same thing!

It started when I covered a dragonfly in luminal. It’s like what cops use to figure out where blood has been. You spray it on things and if there is blood there it’ll glow green when you shine a light on it… it’s so cool.

And you’re using that for evidence?

Yeah… I just need evidence! So I’ve been covering stuff that feels evidentiary in luminal. I covered a dragonfly in it and when I was photographing it, it looked just like… like a disciple of Jesus… it looked like a perfect angel!

I’m deep in a hole of born-again, evangelical faith and this obsession with the angel is so beautiful and feels so poignant… this has nothing to do with the barn *laughs* I’m pretty jazzed about the work though and I’m only photographing them on Polaroid.

But yeah, I guess all that is to say is that the barn feels like a tiny little blip of my practice. It felt good, but not necessarily like progress.

When thinking about your bodies of work, do you consider the “worlds” that you’re creating as intersecting? As in, all the characters, places, etc. as part of a single universe, or are they separate from one another?

I mean, I kind of buy this idea that has been popular in contemporary photography since the 90s, that everyone only has one story to tell.

So even if I were to make work that felt totally different, and obscured compared to the worlds I made before, I don’t think it’d be possible for them to be totally separate. Which is why it feels nice and free to make these super highly saturated rainbow pictures because I think no matter what, they’re coming out of my head. So they’re inevitably going to feel like the same thing.

Also, I don’t really think about or approach photography as a world-building tool anymore. I think about it more critically and theoretically.

But I do think it’s true that just because of who I am, things are going to end up feeling like they’re coming from a specific type of person.

Building off that, I think you have certain motifs that create an inherent layer of cohesion and connective tissue between all your work.

Yeah, I think that’s true, but that doesn’t feel any different to me than somebody going to therapy for a trauma and then having conversations with a therapist about recurring sort of obsessive motifs. That sort of feels like the same thing.

Maybe mine are like… straw… and animals being born *laughs* like those are my sort of motifs.

I didn’t expect you to say straw *laughs* I expected spider webs or something.

Yeah maybe that too, but there are these things that are core to me and I don’t think I’ll ever get away from them. Even if I’m in like New Mexico, in the desert photographing the sun, those things are still a part of me.

Totally, I think even with just the way our mind works, we’re more likely to notice or perceive things that our subconscious is thinking about.

Yeah, but I think it’s deeper than that. Even if I’m swimming, there’s like… there’s part of me that feels a sort of affinity to like… a New England gas station. Do you know what I mean?

I just think there’s no way for me to photograph something that isn’t going to lead back to… not necessarily a world or like an emotional space, but it’s gonna lead back to something…

And I think that thing is a New England gas station *laughs*

I feel like I’ve heard you talk about them a lot… Isn’t it in the artist’s statement about what the rain might bring? Like didn’t speak about stopping at a gas station?

Oh yeah… Yup!

And then you talk about coffee at a gas station a lot too…

Mmhmm I love gas station coffee.

It’s interesting… like I wonder why that? Have you thought about it at all?

Oh yeah, all the time! I mean, I think it’s just like core to where I was when I started to recognize the world as a complicated place, where I could put emotional and theoretical ideas and I think that’s part of why I’m so into working on my truck right now. It’s like… that space feels really generative.

The coffee in particular is about my hands… and how cold they get *laughs* it’s like a $2 hand warmer… and then you can drink it! *laughs*

It’s awesome!

7/11… thank you…

I want to get sponsored by 7/11 or Green Mountain… that’d be so sick.

Can you talk about how your approach and thinking about photography has shifted? Like in terms of the more theoretical approach?

I’ve been seeing a lot more paths into image construction through ideas and not necessarily through… actually, this is a false dichotomy that I’m presenting, in a way that’s hard to talk about because I don’t think that the two modes of making are imagine-based and reaction-based… but I do feel like in this book in particular, I’m thinking about imagination as the method of coming up with an image. And in doing that, I think I have a lot more access to photo theory, and that’s kinda nice. Like I can read a Mark Fisher essay and react to it as an image in a way that I don’t feel like I can, or want to in a bigger practice.

It’s also not poetry! I think that’s part of it… maybe that’s it. With the way I’d been thinking about it, it’s really easy to think of photography as poetry, and this is not that. This book feels like it’s about something else.

Is music still your biggest source of inspiration? Even in the making of this book and your ongoing projects?

Oh yeah, I don’t look at any photography.

Music feels like a different way to think about things that I’m interested in. It’s a different avenue into that.

I know we’ve talked about black metal in the past, is that still a big influence?

Yeah absolutely, maybe not the biggest though. I feel like I listen to a lot of ambient, droney, folky stuff.

I’ve also been listening to a lot of country pop. There’s something about really catchy music about really complicated cultural ideas that I find really fascinating.

That makes a lot of sense, and I feel like it even encapsulates some of the design choices. Like especially the hot pink highlights. Can you talk about that, and how you went about designing the barn?

Well, there’s part of this that I was thinking about…

Part of the book design was pretty influenced by thinking about ghosts in the context of the class I was teaching (Lies, Rituals, and Apparitions). I was spending hours a week thinking about lectures for that class, and part of that was thinking about lost futures. And like, if a thing is haunting past, then what is the thing that’s haunting future… and it’s sort of capitalism, or cultural oppression… so then there’s no future… and if there’s no future… then why are we having this sort of rebirth interest in Afro-futurism and queer-futurism?

Like that’s exciting to me, and it feels really not cynical and not ironic… and pretty hopeful… and cute!

I think part of that is this: I’m interested in queer theory as a motivator for futurism and if I’m making a book that feels like it’s about imagination, and not about external validation, then there’s obvious queer-futurism in that, and so, might as well commit to it *laughs*

Which is why there’s pink!

I feel like most of your work doesn’t have much accompanying text, yet here there’s a pretty lengthy excerpt that acts as a preface here, can you talk about that choice?

Totally. The writing is just a page from my journal, word for word.

It felt important to have first since that little blob of text helps prepare the reader for something really narrative and about place, be it imagined or not. I was reading My Year of Rest and Relaxation, the Ottessa Moshfegh book, and then after that, I read Lapvona, which is like her folklore book. Reading the same person go from memoir to like aggressive novel was so cool! I kind of wanted to do the opposite. I felt like I had been making a lot of folklore, and so, what if I made a memoir?

I know we talked about it a little, but is the barn also like home then? It also feels as though it takes on your identity and is almost more like an entity.

Yeah, I think that’s fair… It sort of feels like something I can plop identity onto.

I was also thinking about what studio space is, and what it means to have a studio as a photographer… which is sort of stupid. Or at least stupid for the type of photography I’m interested in, which is out in the world, but then all of a sudden I had two studios, and one of them was a barn. So making the work felt like a test to understand my interest in imagination being housed in space, and a space I felt really familiar with. There’s probably no other type of structure that I spend more time in than a barn.

Are there any other mediums, outside of music, that have been influential? Maybe some writing, I know you mentioned Mark Fisher at one point.

Yeah, Mark Fisher and Otessa Moshfegh for sure…

Oh, this trilogy of books Fox Fire, so good! It’s so beautiful… the book as an object and the stories… both so beautiful. The writing is vernacular so it’s barely understandable, it’s like 1930’s Appalachian accents… it’s so awesome. That book was an inspiration to some of these pictures.

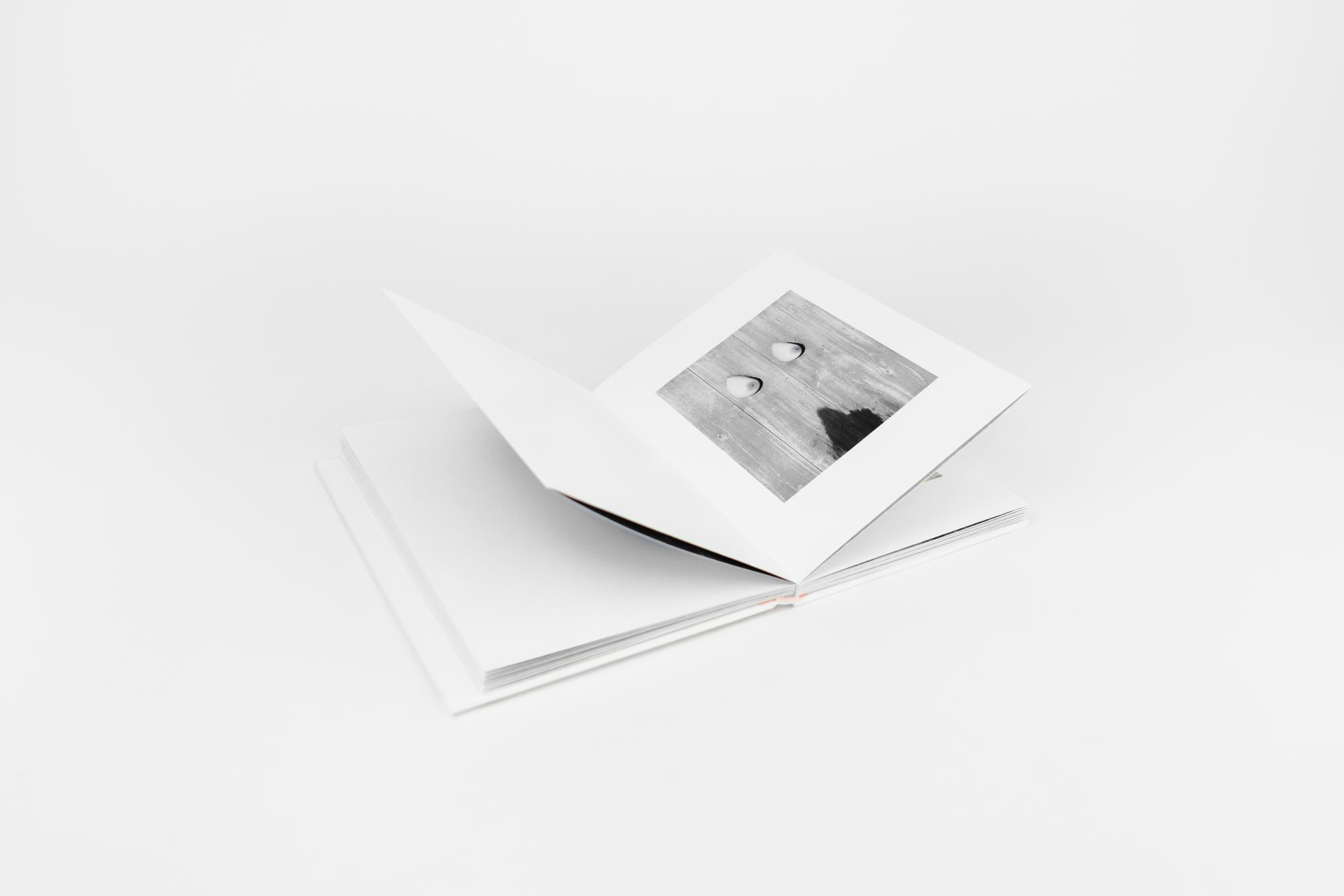

As for other mediums? I spent a good amount of time looking at design in the process of this book, which I don’t usually do. The extremely obvious reference to the barn is Irma Bom’s book, Weaving as Metaphor, which is a book by Sheila Hicks, and designed by Irma Boom, it’s unbelievable! She also did a book for Gucci that had no ink in it, which was what I wanted to do. I wanted to make a book with no ink in it other than the photographs. Which is why all the plates are not inked.

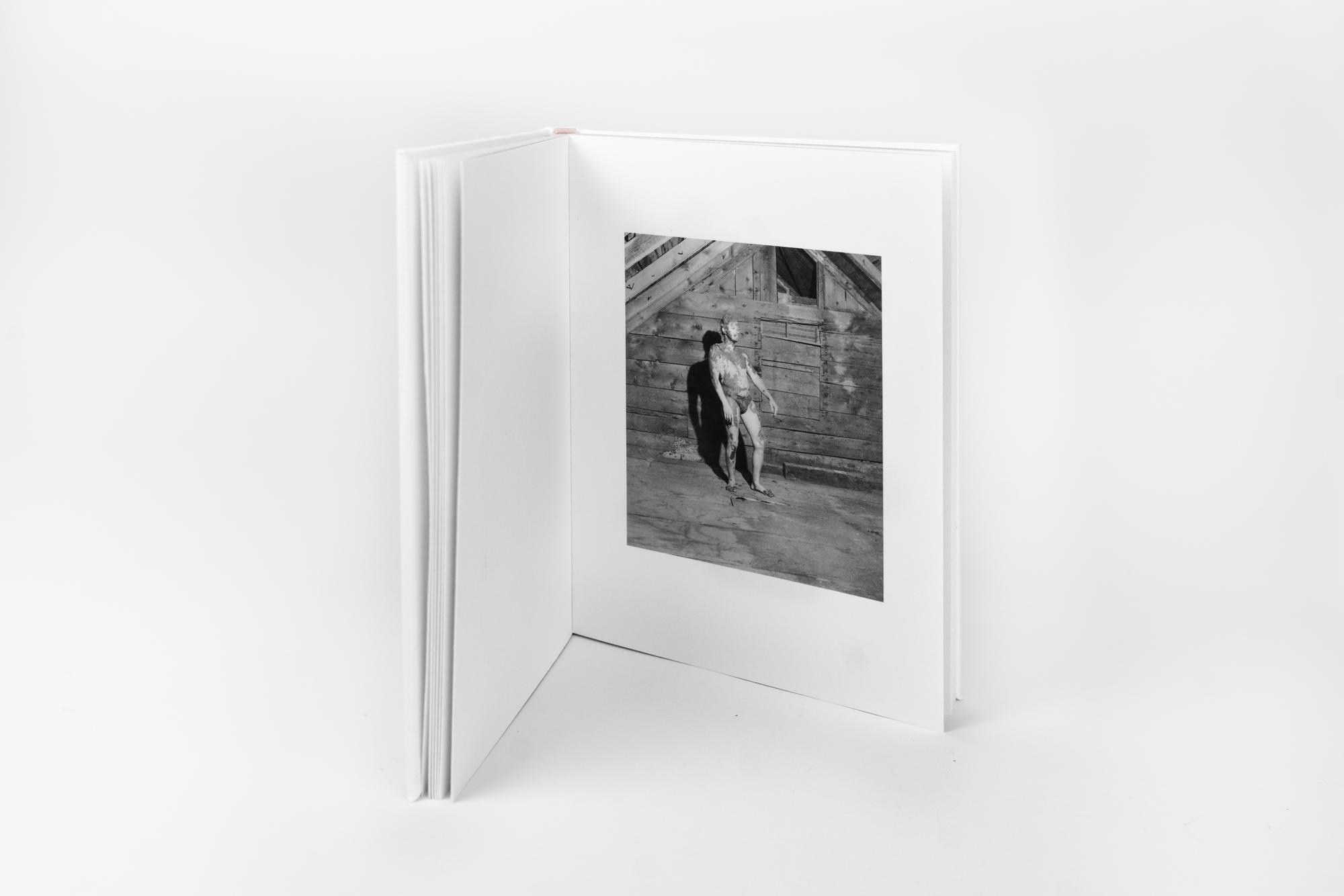

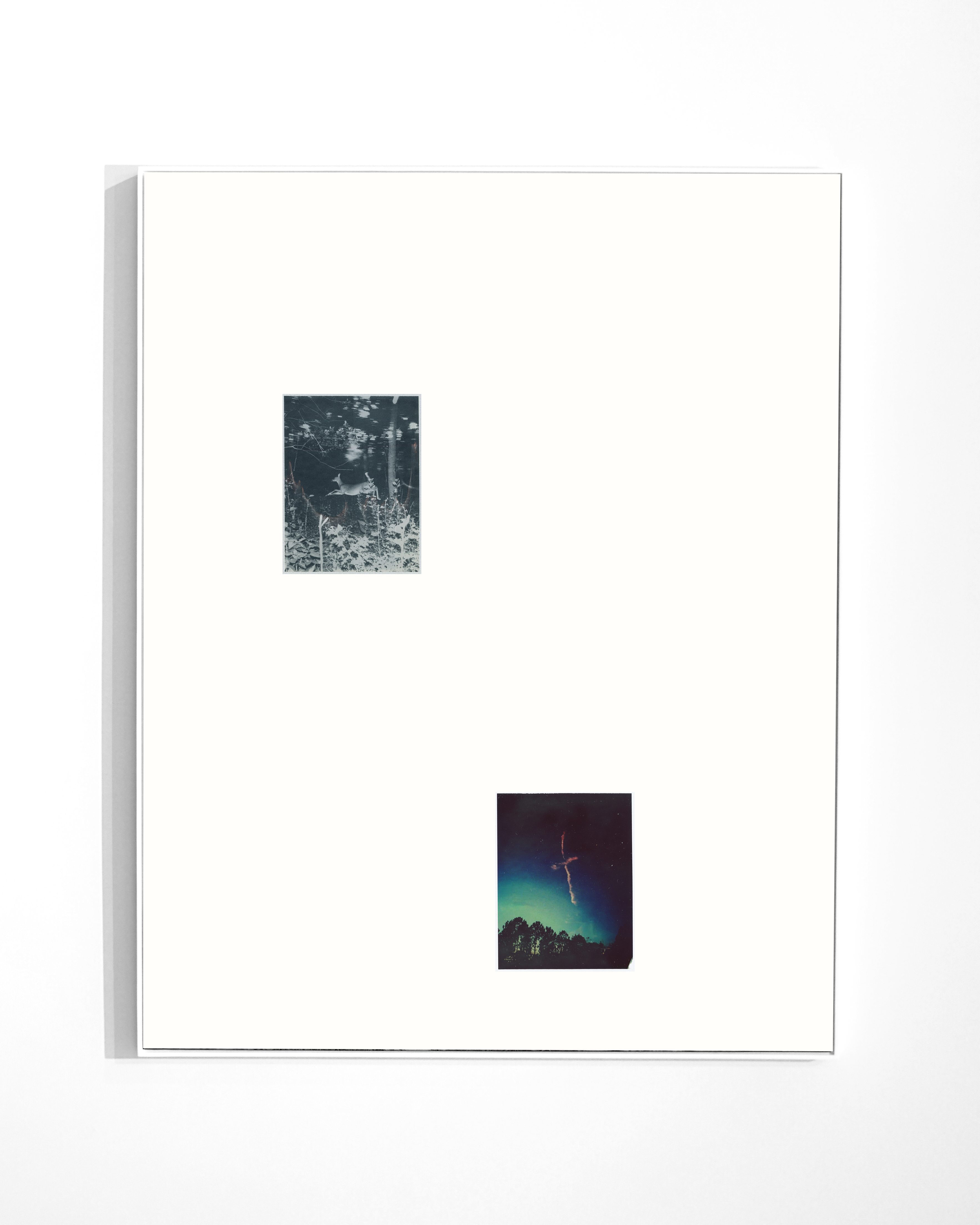

“the barn is a book of photographs made during the summer and fall of 2023 all in a single barn that served as my studio. the barn exists as a church—a sanctuary—a queer future—a (non)functional space of imagination.

the barn consists of 30 plates. the pages are french-folded and bound backward, printed on the inside of the fold are 15 images of moths that came to the window of the barn while i photographed every night. the entire book is printed on awagami washi bamboo paper.

the cover, endpapers, title page, and text is letterpressed with handmade polymer halftone plates, the spine is foil stamped with linotype. it is perfect bound into a block, which is bound into a hardcover. all of this was made possible during my time as the book arts resident at maine media college.”

Dylan Hausthor is an artist based on the coast of Maine. They received their BFA from Maine College of Art and MFA from Yale School of Art. They were a 2019 recipient of a Nancy Graves fellowship for visual artists, runner-up for the Aperture Portfolio Prize, nominated for Prix Pictet 2021, a W. Eugene Smith Grant finalist, 2021 Hariban Award Honorable Mention, 2021 Penumbra Foundation resident, 2023 Light Work resident, a 2022-2023 Lunder Fellow at Colby College, and the winner of Burn Magazine’s Emerging Photographer’s Fund. Their work has been shown nationally and internationally, and they have three books in the permanent collection at MoMA.

They work teaching ghost hunting, ritual, photography, and mushroom foraging. To write this biography, Dylan contacted a forensic medium, who suggested that they “seemed like someone who was passionate in the things they believed in and who hides messages in what they have to say”.

Follow Dylan:

Jake Benzinger (he/him) is a photographer and book artist based in Rockland, Maine; he received his BFA in photography from Lesley University, College of Art and Design in Cambridge, MA. His work explores the intersection of dreamscape and reality. Through the dislocation of space, he weaves together imagery to construct a world that exists in the liminal, investigating themes of duality, longing, identity, and the natural world.

His work was recently featured by Fraction Magazine, and has been exhibited both nationally and internationally. Jake’s body of work, Like Dust Settling in a Dim-Lit Room (Or Starless Forest), was recently self-published, shortlisted for the 2023 Lucie Photo Book Prize, and sold out of its first edition of hardcover books. A second edition was released in late 2023, coinciding with a solo show at the Griffin Museum of Photography.

Jake is currently a gallery assistant and workshop coordinator, a content editor for Lenscratch, and the founder/lead designer at wych elm press.

Follow Jake:

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Anne McDonald: Self-PortraitsFebruary 17th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Leslee Broersma: Tracing AcademiaFebruary 11th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Ilana Grollman: Just Know That I Love YouFebruary 10th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: jessamyn lovell: How To Become InvisibleFebruary 9th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Julia Cluett: Dead ReckoningFebruary 8th, 2026