Now You See Me at Foto Relevance // Jerry Takigawa

This week, I’m honored to feature six artists who I had the privilege of curating into the group show Now You See Me at Foto Relevance, in an effort to offer a glimpse into the vast complexity and nuance of Asian America. While diverse in their image-making, the artists share a common thread: an urge to be seen and recognized through personal narratives put forth on one’s own terms. As viewers, the intricacies and variations in these narratives help us resist a monolithic interpretation of what being ‘Asian American’ signifies, stretching the term beyond its colloquial, demographic meaning (American citizens of Asian descent) and into a realm that pays homage to its activist roots. In 1968, a group of students at UC Berkeley—many who were influenced by and stood with the Third World Liberation Front, the Black Power movement, and the anti-Vietnam War movement—coined the phrase ‘Asian American’ as an iconic act of political self-determination. As the activist Chris Iijima said, “It was less a marker for what one was and more for what one believed.”

The exhibition is up at Foto Relevance through November 13th, but I hope you’ll join me in celebrating the artists and their stories for a long while to come. – Erica Cheung

—

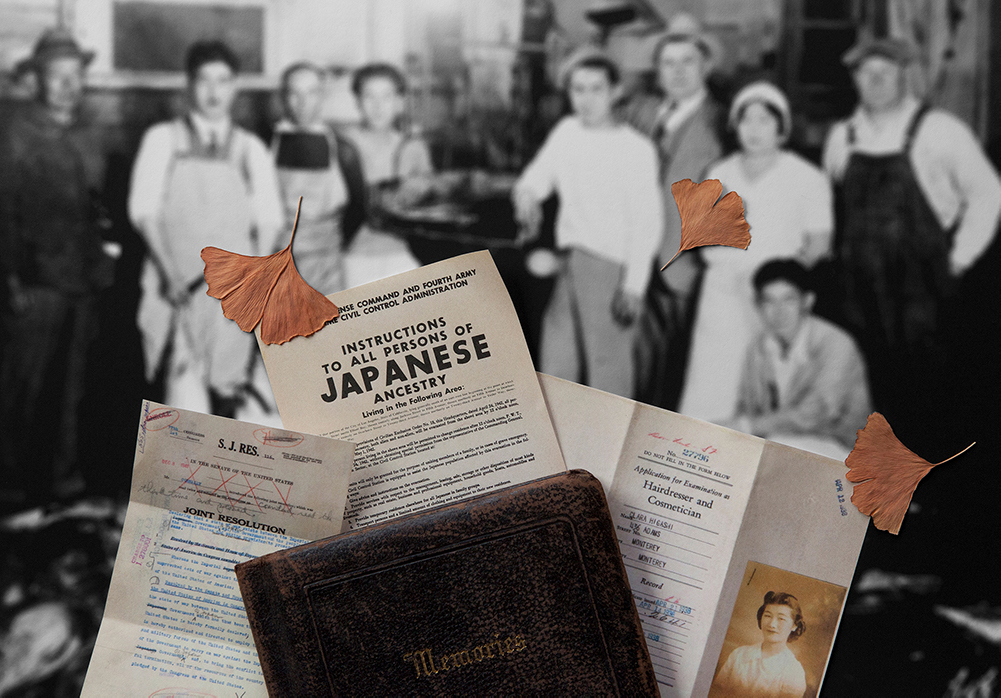

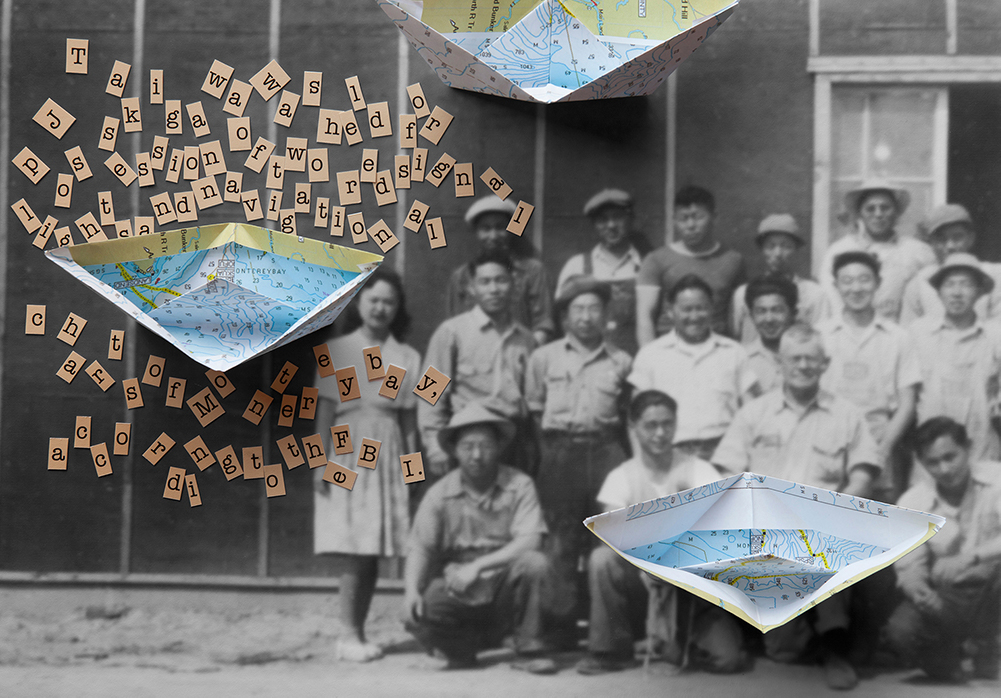

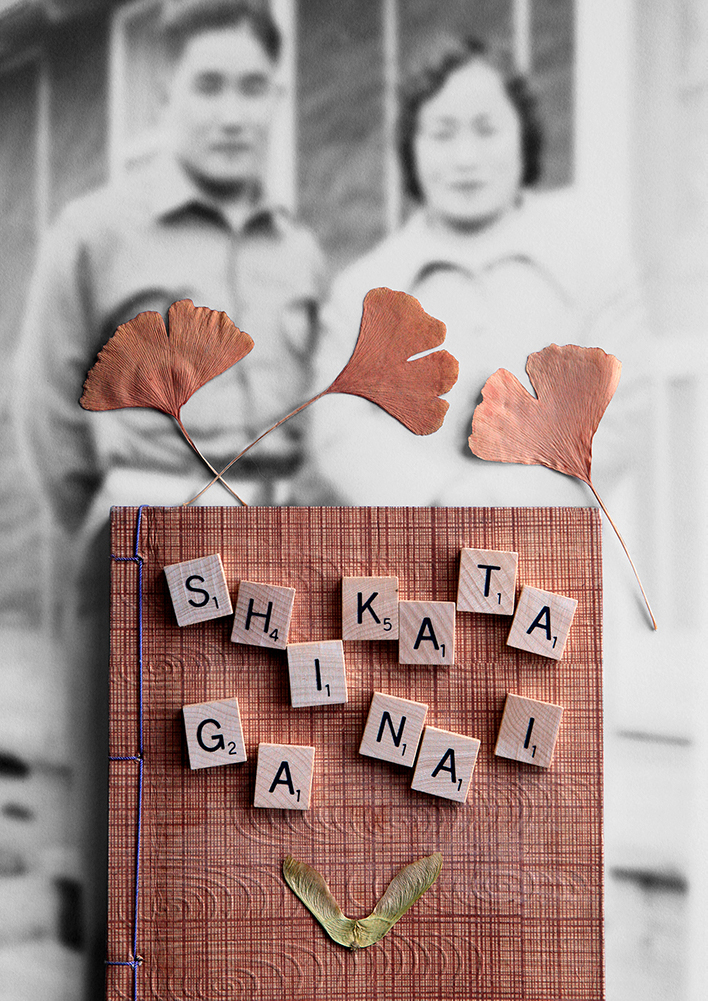

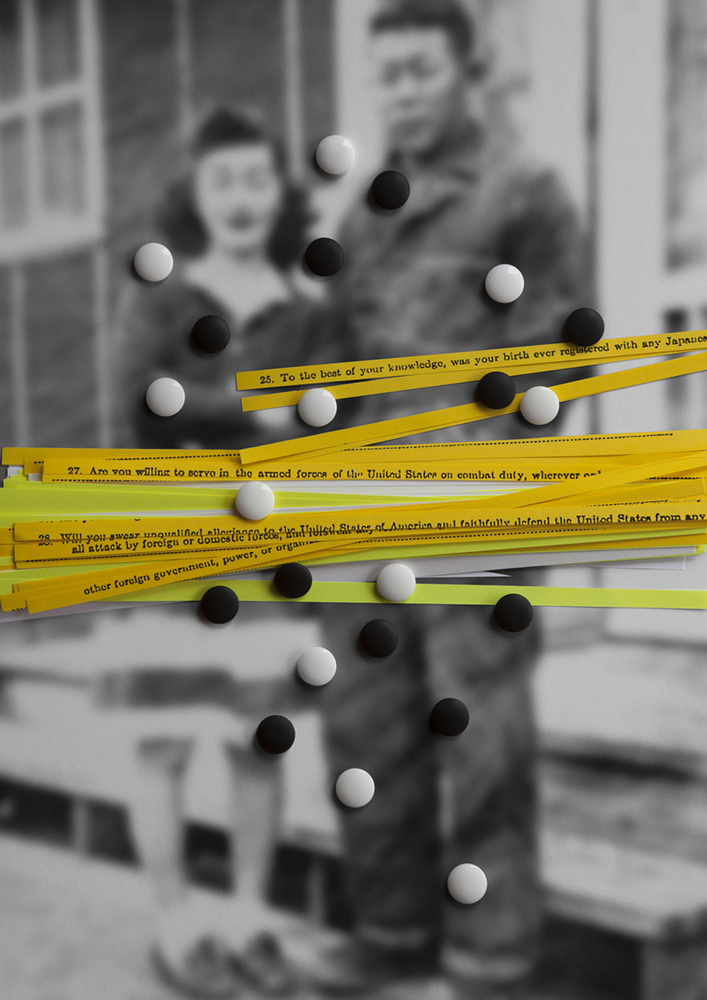

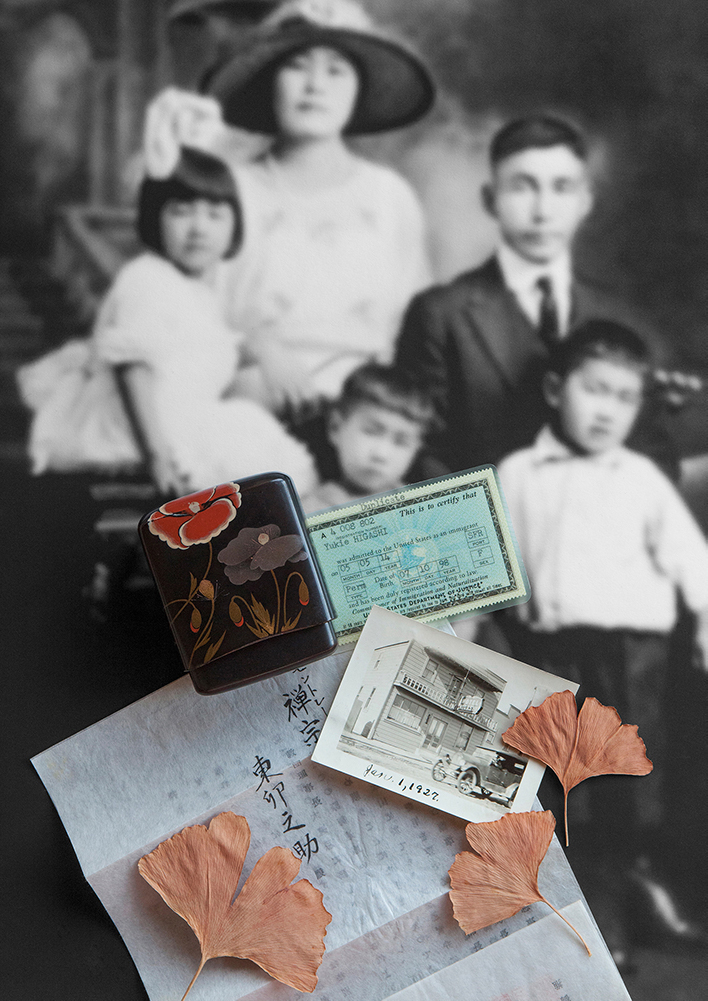

I begin with the work of Jerry Takigawa, whose series Balancing Cultures confronts the histories and repercussions of World War II-era Japanese Internment in the United States. Layering family artifacts and historical documents atop family photographs, Takigawa underscores the fraught tightrope his family—and many other families—walked: wanting to embrace their Japanese heritage while being made to feel as if doing so rendered them less American (despite the fact that many were native-born citizens). While the internment of Japanese Americans ended in March of 1946, the exclusionary ideologies behind it remain at play today for so many—rendering Takigawa’s reach into the past as timely as ever.

I deeply admire the artist for his unflinching courage in sifting through and making records of these histories. An interview follows.

Jerry Takigawa is an independent photographer, designer, and writer. Exhibited internationally, he is the recipient of the Imogen Cunningham Award, the Clarence J. Laughlin Award, CENTER’s Curator’s Choice Award and the Rhonda Wilson Award. His work is in the permanent collections of the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, the Brooklyn Museum, the Crocker Art Museum, the Santa Barbara Museum of Art, the Library of Congress, and the Monterey Museum of Art. He studied photography with Don Worth at San Francisco State University and received a degree in art with an emphasis in painting. Takigawa lives and works in Carmel Valley, California.

Balancing Cultures

Balancing Cultures highlights the structural racism deeply woven into the fabric of our society. A recent discovery of family photographs compelled me to express the shame and loss suffered by my family in the WWII American concentration camps. These images add humanity to the historical record—facts need testimony to be remembered. I give voice to the feelings my family suppressed to remind us that hysteria, racism, and economic exploitation are still active forces in our nation today. The WWII camps, created to assuage American xenophobia, engendered a shadow legacy for an entire generation of Japanese Americans. Left untold, their story remains buried, a casualty of the country they loved and fought for. Silence sanctions—documentation is resistance. —Jerry Takigawa

Thank you so much for taking the time to interview with me/Lenscratch! How have you been doing as of late? Where are you writing us from?

Hi Erica. I’m sitting at home in Carmel Valley, California where the current AQI is 138 so still kind of smoky due to wildfires. We can feel the advent of Fall as the days are getting shorter. I’m doing well considering the new normal.

How did you come to include photography in your art practice? Why photography?

I began as a painting major in college. When I started doing photo-real paintings, I learned photography to facilitate that work. My brother was doing photography then and it was a short hop for me to fall into the darkroom. I think it’s ironic that I first migrated to photography as it allowed me to get out of the studio and into the world to make photographs. I began with environmental and social documentary work. Today, much of my work involves a return to the studio again to construct images. My approach to making photographs still correlates to a fine art painting sensibility.

My curation of Now You See Me at Foto Relevance is an effort to call attention to Asian American voices. What does the label ‘Asian American’ mean to you, and what does it mean for your art practice?

Asian American is a label encompassing dozens of countries of origin. I would have to say that the label is so broad that its meaning is often more applicable to matters such as census. Today, Asian American attributes can be seen as hardworking, educated, and family oriented. Regarding art, I would ask the question “why aren’t there more well recognized Asian American photographers?” I suspect much of photography in America is filtered through a Western gaze. To draw a parallel, work by women artists make up only 3-5% of major permanent collections in the US. With women artists of color, that percentage is dramatically less. I don’t feel overtly discriminated against, but I know I am pushing against long standing predilections of Western aesthetic conventions.

How do other facets of your identity gel with, conflict with, and generally intersect with your Asian American-ness (if at all)? Do these additional identity markers influence the way you approach your work and/or the world at large?

I feel as if I’ve had to grow into owning my Asian American-ness. Because of my parental silence about their WWII experiences and their encouragement to be American as a way of being safe, I had to find my way back to embracing my Japanese roots. Ultimately, I found photography to be a malleable medium that allowed me to express a hybrid Japanese American aesthetic and message. Through photography, I was able to integrate my Eastern and Western points of view. Finding a way to creatively bridge and balance two cultures, is the milieu of all immigrant offspring.

Balancing Cultures bravely lays bare a painful part of U.S. history through photographs pulled from your own family archive. What compelled you to put together the series—especially through such a personal lens? How do the histories behind Balancing Cultures relate to our present day?

We teach what we wish to learn. When I was president of the Center for Photographic Art in Carmel, my friend and fellow board member, David Bayles and I, developed a creativity workshop called the PIE Labs (Photography. Ideas. Experience.). The premise was that artistic growth is inseparable from personal growth. Embedded in that premise is the notion, well expressed by Brené Brown, that to be seen as well as to find your authentic voice, you must be vulnerable. Balancing Cultures required going out on a limb, or at least that’s how it felt initially. Admitting my family had been incarcerated in a concentration camp and seen as the “enemy,” was a difficult step in light of decades of minimizing those events. To share this message to the public, was betraying a family secret. Something powerful happened when I saw the photographs of my parents in camp. What once was a place in anecdotal references, “camp” became more than a story and I wanted to know more. What my family and 120,000 people of Japanese ancestry were subjected to during WWII was ultimately the result of race prejudice, war hysteria, and a failure of political leadership. This was the conclusion of the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Citizens in 1980. It was not military necessity as originally proposed.

Today, the same elements: racism, hysteria, and failure of political leadership, underpin current social issues today. Cathy Park Hong in a New York Times article wrote: “After President Trump called the Covid-19 the “Chinese Virus,” in March (2020), the Asian Pacific Policy and Planning Council said more than 650 incidents of discrimination against Asian-Americans were reported to a website it helps maintain in one week alone.” It’s evident that with very little political/social permission, xenophobia, and the need to blame, lie just under the surface of a civil veneer.

Walk us through the process of creating works in Balancing Cultures (you’re welcome to choose one specific work to write about, if you’d like). How do you choose to pair and assemble specific images, memorabilia, and text?

The vintage family photographs came first. The images of camp were the most compelling. I began by doing research of what happened to the Japanese Americans during WWII. I learned much through reading books, newspaper articles, camp newsletters archived online. I asked some questions of my great aunt who was 103 at the time. All of this research amplified the empathy I had for what my family endured. I felt their pain and I felt my anger. I needed to take a first step toward making an image. I was procrastinating, because I knew I was crossing a line of confidentiality. The first image I made was EO 9066. The background photograph of my family taken in my grandfather’s Japanese garden was printed slightly out of focus. Visually, this pushes it further back especially in contrast to the elements in the foreground that are in sharp focus and natural color vs B&W. All of the elements and artifacts are selected intuitively—i.e., I rely on my instincts to know when something is right. Using the headline from the “Notice to all persons of Japanese Ancestry” poster was a natural—to shred the text imparted emotion.

What has been one of your favorite reactions or responses that someone has had to your work?

I welcome all levels of feedback. There are people who didn’t know about these concentration camps at all. There are people who empathize with the pain of the injustice that was caused. Many say the images are a mix of moving, powerful and beautiful—that they add to the understanding of what happened. For example, here are two comments from recent artist talks: “You are doing your part to celebrate diversity and bring forth the healing that is needed for each and all of us.” And: “This history needs to be shared widely and appreciated; now, before it is buried and forgotten.” All of these reactions contribute to a feeling of being seen—for my family, our story and myself.

Whose work are you looking at and thinking about (from the Asian diaspora or otherwise, photographic or otherwise)?

Like most artists, I look at a lot of work. When I see something I wish I’d done, I’ll make a mental note of it. It’s what I’ve always done. For example, this year’s Critical Mass Top 50 is a collection of beautiful portfolios. I like all of them. Some closely pique my interest or my aesthetic. I want the aesthetic to draw me in and the artist statement to seal the deal. I was particularly fond of Jordanna Kalman, Ervin Johnson, Pep Ventossa, and Astrid Reischwitz. I recently finished The Story of More by Hope Jahren that moved me to want to do a project about climate change.

What are you looking forward to? What’s next?

I’m currently working on a book project for Balancing Cultures. It’s been a slow process but there’s light at the end of the tunnel with a projected release in January 2021. The book is another vehicle to share the photographs and the narrative with a larger audience. I look forward to more exhibitions and book talks next year. After Balancing Cultures, I welcome the creative void in which all things are possible. It’s the unnerving and delicious period that follows the end of one project—where the next work is born.

Future events involving Balancing Cultures:

What Will You Remember, Viewfinder Palimpsest

Curated by Karen Haas, Lane Family Curator of Photography, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

https://www.whatwillyouremember.com/palimpsest/

Woodstock Center for Photography, Photography Now 2020

Curated by Andy Adams, FlakPhoto.

Opens November 7, 2020

Center for Photographic Art, International Juried Exhibition

Juried by Aline Smithson, Lenscratch.

November 14 – December 20, 2020

Center for Photographic Art, Jerry Takigawa, Retrospective

Curated by Helaine Glick.

January 9 – February 14, 2021

San Joaquin Delta College, LH Horton Jr. Gallery

, American Concentration Camps

Curated by Gail Enns, Celadon Arts.

January 21 – February 26, 2021

Griffin Museum of Photography, Balancing Cultures

Curated by Paula Tognarelli, Executive Director and Curator.

April 1 – May 23, 2021

Viewpoint Gallery, Balancing Cultures

Curated by Karen Connell, Viewpoint Curatorial Committee.

September 7, 2021 – October 2, 2021

Monterey Museum of Art, American Concentration Camps

Curated by Gail Enns, Celadon Arts.

September 9, 2021 – January 9, 2022

Social:

IG—jerrytakigawa

FB—facebook.com/jerry.takigawa

Twitter—@takigawadesign

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Photography Educator: Lindsay MetivierFebruary 21st, 2026

-

Jonathan Silbert: InsightsFebruary 19th, 2026

-

Olga Fried: Intangible EncountersFebruary 18th, 2026

-

Anne McDonald: Self-PortraitsFebruary 17th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Leslee Broersma: Tracing AcademiaFebruary 11th, 2026